By Bennett Sherry

The collective learning behind collecting gases

Humans first inferred long ago that changes in our climate affect our lives. Foraging societies have been adapting and migrating in response to climactic changes for millennia. Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers wrote about the relationship between human activity and the environment as early as the fourth century BCE. Scholars in the Islamic Golden Age developed meteorological instruments and methods. In the eleventh century CE, a Chinese scholar named Shen Kuo offered what is probably the first theory of gradual climate change after he found petrified bamboo in a region where the plant could no longer grow. And in 1640, a Flemish chemist named Jan Baptist van Helmont first identified the gas carbon dioxide (CO2), which we now know is one of the most important greenhouse gases driving climate change.

All these innovations and discoveries were significant, but only recently have we begun to understand the mechanisms by which human activity might reshape the climate and thus the actions we can take to manage this process. You might be surprised to learn that the first steps on that road were taken by an American woman named Eunice Foote in 1856.

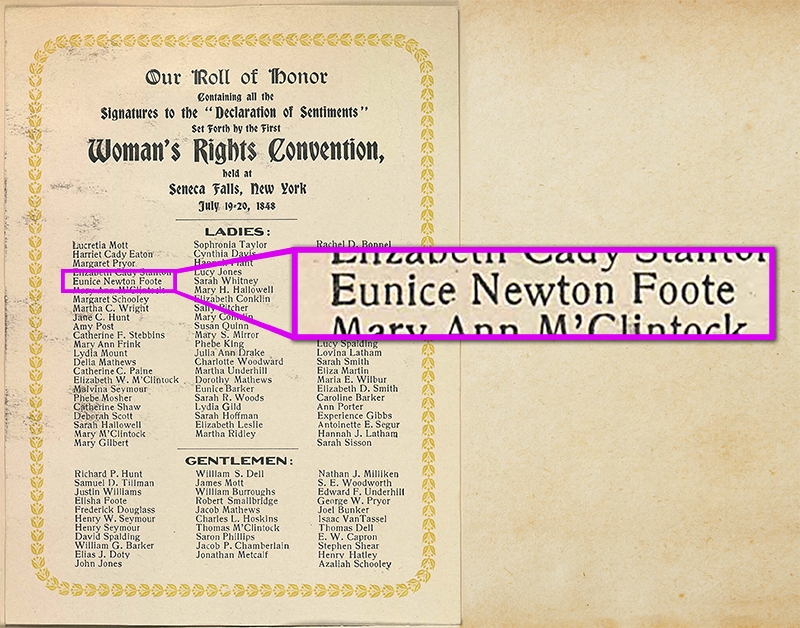

An amateur scientist and social activist, Foote was a campaigner for women’s suffrage and one of the signers of the “Declaration of Sentiments” drawn up at the Seneca Falls Woman’s Rights Convention in 1848. Today, however, she is best known for her experiments demonstrating the atmospheric heating potential of CO2—now known as the greenhouse effect.

Detail from The Roll of Honor listing the women and men who signed the “Declaration of Sentiments” at the first Woman's Rights Convention, July 19-20, 1848. Library of Congress, public domain.

Detail from The Roll of Honor listing the women and men who signed the “Declaration of Sentiments” at the first Woman's Rights Convention, July 19-20, 1848. Library of Congress, public domain.

Foote used two glass cylinders for her experiments. She filled the cylinders with different gases and air at different moisture levels and exposed them to sunlight. Her surprising conclusion was that cylinders filled with moist air warmed more than those with dry air, and that cylinders with CO2 reached the highest temperatures. Foote wrote, “The receiver containing this gas became itself much heated—very sensibly more so than the other—and on being removed [from the Sun], it was many times as long in cooling.” She concluded that “an atmosphere of that gas would give to our Earth a high temperature.”

Foote’s remarkable scientific achievements were forgotten by the scientific community, despite her publications in the American Journal of Science and Arts and Scientific American and an academic presentation. She was an amateur and a woman in an era when people in both categories were often dismissed. Yet her work preceded by three years that of British scientist John Tyndall, who is sometimes called “the father of climate science.” Tyndall is credited with proving a connection between greenhouse gases and a warming atmosphere using experiments with infrared light. His work neither credited nor referenced Eunice Foote. There is reason to believe that Tyndall, who worked in London, had never heard of Foote’s work in America. There is also reason to believe that her ideas had been dismissed by English scientists.

The changing science of climate change

Both Foote and Tyndall lived at the height of the Industrial Revolution. By the time they were publishing, humanity’s use of fossil fuels had already begun to reshape the planet in disturbing ways. Yet neither scientist was much alarmed by their findings. Both had identified the mechanisms of atmospheric warming, but neither comprehended its significance. Industrialization was changing the landscape of their homes, and it was polluting large industrial centers like London and New York. Still, the idea that human activity could fundamentally transform the climate of the entire planet remained unthinkable.

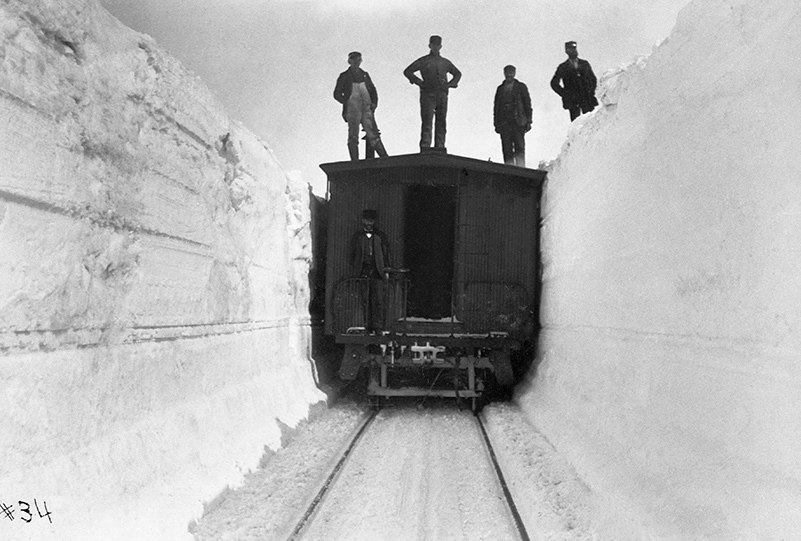

Instead, at the end of the nineteenth century many scientists were predicting an impending global ice age, rather than global warming. Only in the early twentieth century did scientists begin to understand that increasing amounts of CO2 released by industry might warm the planet. But they weren’t worried. After the extraordinarily harsh winter of 1880, a little global warming was a happy prospect. In fact, well into the twentieth century, scientists frequently ignored new evidence of global warming trends, dismissing concerns and often arguing passionately against the idea that greenhouse gases would noticeably heat up our world.

A freight car in the United States surrounded by snow during the “Long Winter” of 1880. © Minnesota Historical Society / Corbis Historical / Getty Images.

A freight car in the United States surrounded by snow during the “Long Winter” of 1880. © Minnesota Historical Society / Corbis Historical / Getty Images.

A history of potential solutions

All of which is to say, our understanding of the processes driving climate change isn’t new, even if our sense of urgency about it is. But did you know that some of the technologies that might help us get to zero also have surprisingly long histories? Solar, wind, and hydropower had all been used to produce electricity by the time scientists first became concerned about climate change. For example, the first large-scale solar power plant was built by the U.S. engineer Frank Shuman in British-controlled Egypt in 1913. It was a solution to the problem of pumping water from the Nile River into cotton fields. But soon this technology was being surpassed by the discovery of oil in nearby Iran. By the beginning of World War I a year later, British leaders became convinced that fossil fuels, not the sun, should power the future of the British Empire.

Frank Shuman’s solar panels in the Cairo suburb of Maadi. © ullstein bild Dtl. / Getty Images.

Frank Shuman’s solar panels in the Cairo suburb of Maadi. © ullstein bild Dtl. / Getty Images.

The Climate Project is all about the future—finding ways to ensure that our future on this planet is possible—but history offers important lessons about the pitfalls and potentials of climate science. It can remind us that we have learned a great deal in a short time, that there is so much left to do, and that we have always been capable of extraordinary innovations. Stories of people like Eunice Foote are reminders that diverse voices must be part of the science and the solutions we develop. Climate change is happening. It is the result of a long history of human action and inaction. It will affect us all. Understanding the science behind why our climate changes and figuring out how we might innovate our way to net-zero greenhouse gases, will require contributions from a lot of people—yesterday, today, and tomorrow.

About the author: Bennett Sherry holds a PhD in history from the University of Pittsburgh and has undergraduate teaching experience in world history, human rights, and the Middle East. Bennett writes about refugees and international organizations in the twentieth century and is one of the historians working on the OER Project courses.

Cover image: Cartoon depicting Londoners who were convinced that the new Ice Age had begun. Cartoon depicting Londoners who were convinced that the new Ice Age had begun. The winter of 1880/ was more severe than usual in Britain which sparked these theories. Illustrated by George du Maurier (1834-1896) a Franco-British cartoonist and author. © Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,