By Trevor R. Getz, Bridgette Byrd O’Conner, and Bennett Sherry

OER Project Team

Writing is a tool of immense power. It allows us to pass our knowledge to descendants. It has sparked wars, enshrined peace, and allowed us to harness the power of the atom. Ancient peoples appreciated this power as much as we do. Take for example one of the oldest pieces of writing we have: a tablet from a Mesopotamian man named Nanni, who used the awesome power of the written word to… file a customer service report.

In the year 1750 BCE, Nanni sent his servant to buy copper from a merchant named Ea-Nasir. Things did not go well. Ea-Nasir had purchased copper from a city in Arabia. On his return to Ur, he began selling the copper, but it appears the metal was substandard, and his customer service even more so. After Ea-Nasir mistreated Nanni’s servant, Nanni wrote the 1750 BCE equivalent of an extensive Yelp review. His diatribe, which covered two sides of a clay tablet, admonished the merchant: “What do you take me for, that you treat somebody like me with such contempt?” If you’ve ever had to wait on hold to talk to your internet service provider, no doubt you can relate. And Nanni was hardly alone. Archaeologists unearthed many more tablets containing customer complaints in Ea-Nasir’s house, and it appears he eventually fell on hard times.

We really owe a great deal to Ea-Nasir’s lack of business acumen. Writings like these customer-service complaints give us a richer picture of life in the ancient world—they show us complex networks of trade and communication stretching across the Persian Gulf, Mesopotamia, and the Arabian Peninsula. Had Ea-Nasir believed that “the customer is always right,” we’d know a lot less about his world.

Writing history

Writing and history have a bunch of connections. Of course, writing helps define the human past. The advent of writing created enormous potential for humans to organize, learn, and pass on information through what we at the OER Project call collective learning, a key through line in both our World History Project and Big History Project courses. Suddenly, information could be recorded, stored, and shared like never before. People quickly discovered just how useful this was. The earliest bits of writing that we have were scratched on clay tablets about 5,000 years ago. These early texts were bookkeeping symbols used to keep track of property, but they were soon joined by laws, religious texts, stories, and Nanni’s customer-service complaints. Kings and emperors found writing useful for ruling larger and larger territories. Writing systems helped rulers count people and goods, which helped them raise taxes and armies more efficiently. Plenty of emperors and kings ruled over realms with several written languages.

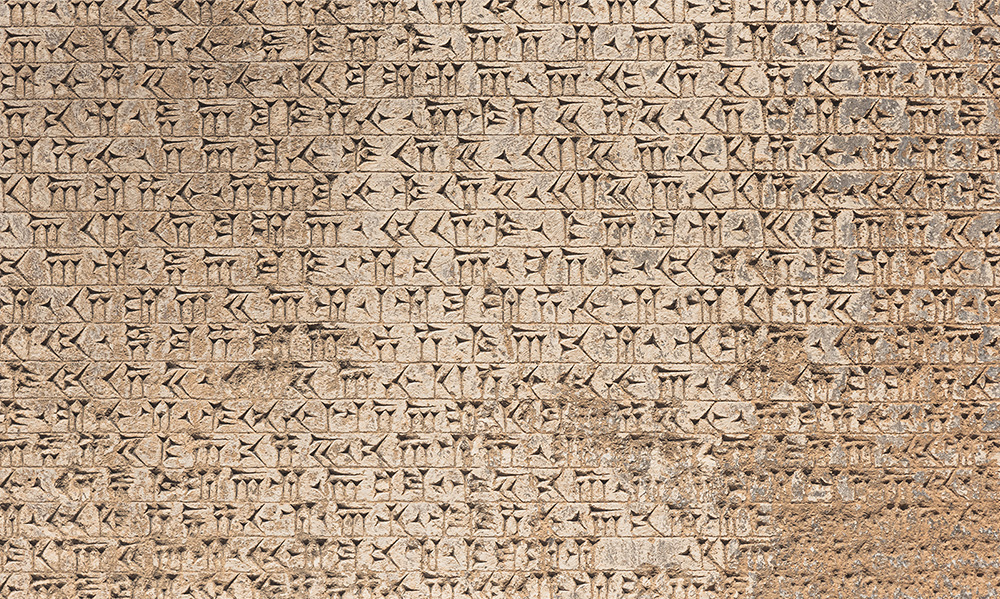

A message from Persian emperor Darius the Great, dating from the fifth century BCE, Kermanshah Province, Iran, written in three languages: Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian. © Jean-Philippe Tournut / Moment / Getty Images

A message from Persian emperor Darius the Great, dating from the fifth century BCE, Kermanshah Province, Iran, written in three languages: Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian. © Jean-Philippe Tournut / Moment / Getty Images

And the world has had many different written languages indeed. Some use mainly ideograms and pictograms, which directly represent things or ideas. Most, however, use alphabets, sets of letters or characters that represent sounds which are arranged to form words. The most influential of all of these was the Phoenician alphabet from which the first two letters—aleph and beth—we get the word alphabet. Our own “Latin” alphabet, the one used to write this blog post, is descended from this original set of letters. So are the Greek alphabet, the Cyrillic alphabet used in Russia and surrounding regions, and the Georgian and Armenian alphabets.

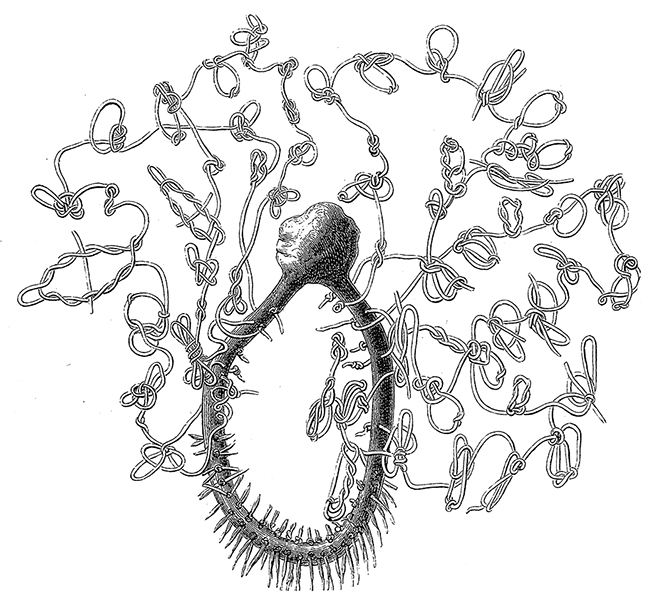

Many parts of the world, of course, did not have alphabets until recently. That doesn’t mean they didn’t have writing systems, however. For example, the empire of the Inca ran on a sophisticated set of accounting records known as quipu, which were based on carefully tied notes stored on longer cords. Unfortunately, many of these quipu were destroyed, both purposefully and by mistake, during the early years of Spanish rule in South America. However, scholars have recently begun to determine ways in which the quipu functioned not only as tax and financial records, but also a system of writing. There is also evidence of older systems of writing in this region, including a system known as quellca, which the Inca themselves banned around 1470.

A rendering of an Inca quipu. © Nastasic / DigitalVision Vectors / Getty Images.

A rendering of an Inca quipu. © Nastasic / DigitalVision Vectors / Getty Images.

The fact that governments have, at times, banned writing systems as well as particular pieces of text demonstrates the enormous power of writing. Historians, of course, know that power. First of all, we know that written sources are powerful ways of not only communicating but also for preserving knowledge. Although we historians now look to all kinds of other types of sources—linguistic, artistic, archaeological, botanical, oral—our representations of the past are still often dominated by what evidence we find in written remains.

Historians now recognize that we need to place more attention on studying societies that didn’t have writing systems. We communicate in a variety of ways, including through documentary video and comics. Yet writing remains a powerful tool for quickly, efficiently, and accurately communicating what we know. And of course, writing continues to evolve. Short-form communication like texting has become more important recently; digital publication allows us to search texts rapidly for ideas and terms; and translation software reads texts in one language and can reproduce them in ever-increasing accuracy in another.

Humans are writing more than ever. Some day in the future, a historian will have to sift through thousands of tweeted and texted customer-service gripes, much as we study Nanni’s angry carvings today. For these reasons and more, writing remains the key to collective learning in our society, and an important skill to teach and learn in your classroom.

About the authors:

Bridgette Byrd O’Connor holds a DPhil in history from the University of Oxford and has taught the Big History Project and World History Project courses and AP US government and politics for the past 10 years at the high-school level. She currently writes articles and activities for WHP and BHP. In addition, she has been a freelance writer and editor for the Crash Course World History and US History curricula.

Bennett Sherry holds a PhD in history from the University of Pittsburgh and has undergraduate teaching experience in world history, human rights, and the Middle East at the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Maine at Augusta. Additionally, he is a research associate at Pitt's World History Center. Bennett writes about refugees and international organizations in the twentieth century.

Trevor Getz is a professor of African history at San Francisco State University. He has written 11 books on African and world history, including Abina and the Important Men. He is also the author of A Primer for Teaching African History, which explores questions about how we should teach the history of Africa in high school and university classes.

Cover image: Engraved illustration of study of a scholar in the 15th century. © mikroman6 / Moment / Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,