By Bennett Sherry

At this point in the year, if you were to ask your students to draw a picture of collective learning, I’m guessing they’d draw something like this:

Over time, people pass on knowledge to their descendants, each generation building on the one before. Thus, we move from sharp sticks to intercontinental ballistic missiles. But you—and probably your students—know that collective learning doesn’t move in a straight line. There are lots of bumps and hiccups, and knowledge is often lost. For example, only in the last five years have scientists discovered why Roman cement was so durable.

How do we know what we know about the past, and how has that knowledge changed over time? People have often used knowledge of the past to shape their future. The picture below is proof of that, and it’s proof that the path of collective learning is unpredictable.

The Polynesian voyaging canoe, the Hokule'a, arrives in the port of Tahiti in 2022, after journeying from Hawaii. © Suliane Favennec / AFP / Getty Images.

The Polynesian voyaging canoe, the Hokule'a, arrives in the port of Tahiti in 2022, after journeying from Hawaii. © Suliane Favennec / AFP / Getty Images.

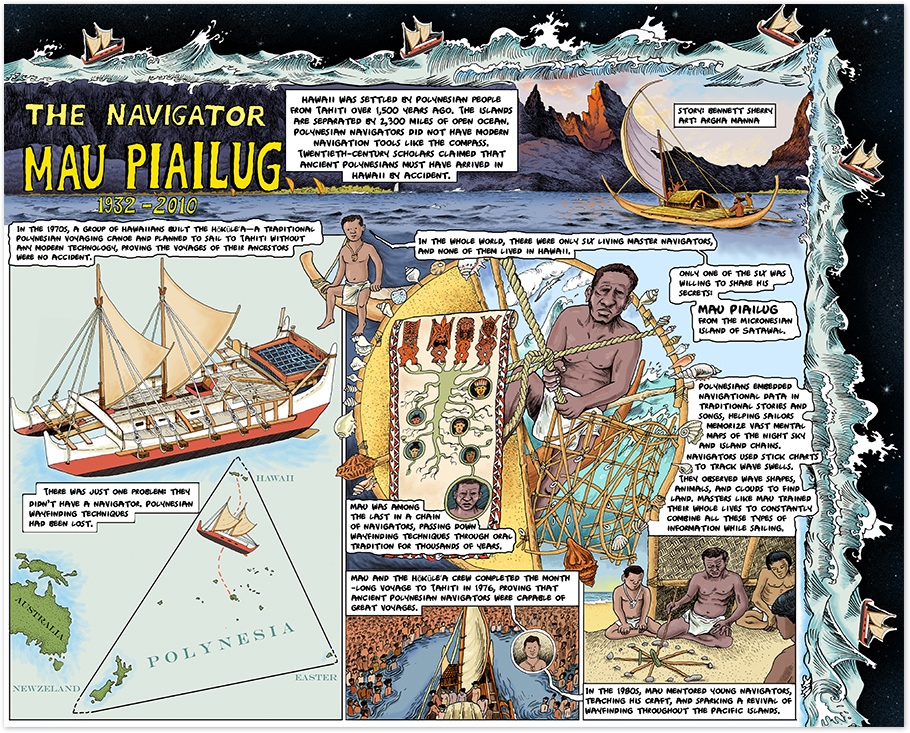

This is a picture of a traditional Polynesian voyaging canoe called the Hōkūle‘a. The story of the Hōkūle‘a starts 50 years ago, but it also begins thousands of years ago. It’s a story of collective learning lost and reclaimed. It’s also the story of a man named, the subject of one of the new graphic biographies in BHP. These one-page comics tell hidden stories in the history of collective learning. Many of these biographies, like Mau’s, are just as relevant in WHP classrooms. (See: Ibn Khaldun, Ibn Bassal, Ales Hrdlicka, and George McJunkin.)

Graphic biography of Mau Piailug. Click to enlarge. By OER Project, CC BY-NC 4.0.

Graphic biography of Mau Piailug. Click to enlarge. By OER Project, CC BY-NC 4.0.

Finding wayfinding

Mau’s graphic biography begins with the story of a group of Hawaiians who, in the 1970s, established the Polynesian Voyaging Society and set out to prove that their ancestors were capable of great voyages—that they had, in fact, traveled the 2,000 miles from Tahiti to Hawaii on purpose.

Ancient Polynesian navigators led their people on migrations across the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean without navigational instruments like the compass, astrolabe, or GPS. The Polynesian Voyaging Society built the Hōkūle‘a and prepared to make a voyage from Hawaii to Tahiti using only the methods their ancestors had used 1,300 years ago.

There was just one small problem: they didn’t know those methods. Thanks to centuries of colonialism in the Pacific, much knowledge had been lost. By the 1970s, there were only a handful of master navigators remaining, and none of them were Polynesian. To make matters worse, most were reluctant to share their knowledge. Navigators held positions of prestige and passed down secret navigational knowledge from generation to generation, from masters to apprentices. Only one man was willing to share his knowledge: Mau Piailug, a master navigator from the Micronesian island of Sahwall.

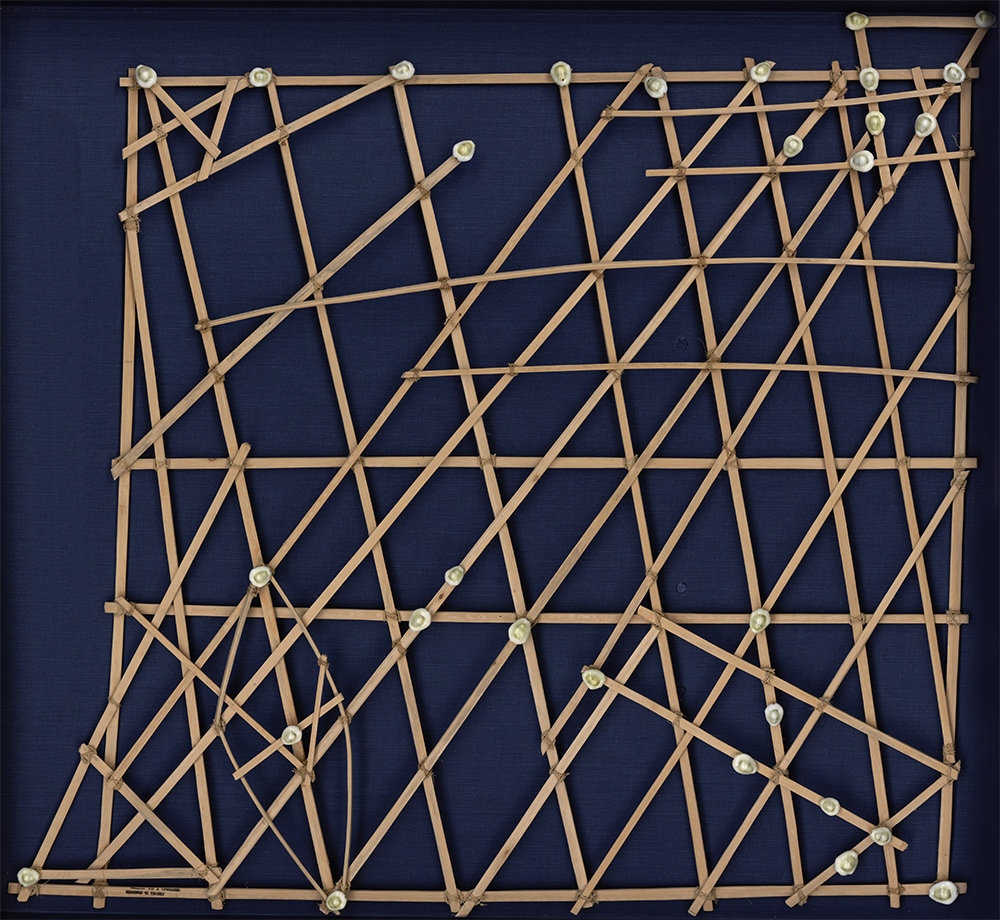

Mau agreed to lead the Hōkūle‘a and share wayfinding techniques with its crew. These techniques included stories, songs, and memory devices that helped navigators memorize the night sky and endless chains of islands; tools like stick charts that help Micronesian navigators track ocean currents in relation to a particular island; and observational data about wave shape, weather, and sea life. Mau stayed awake for most of the voyage, constantly processing all these different types of data to keep the canoe on course. The voyage was a success and the crew’s arrival in Tahiti helped launch a revitalization of Polynesian wayfinding techniques.

Micronesian stick chart. © Hulton Archive/ Getty Images.

Micronesian stick chart. © Hulton Archive/ Getty Images.

Oral traditions

The long history of collective learning behind Polynesian wayfinding, its near disappearance, and its revitalization offer an important lesson. Wayfinding was knowledge gained by centuries of mariners setting off into the unknown to find new islands and learn new routes. Countless mariners must have died in the pursuit of new knowledge. By the time Captain James Cook arrived in the Pacific in the eighteenth century, Polynesian navigators were masters of their craft. One navigator, Tupaia, drew a map for Captain Cook. On it, he recorded the relative locations of 130 islands, naming 74 of them, in an expanse of the Pacific Ocean the size of the continental United States. He did this all from memory.

Historians generally privilege written sources over other types of evidence. Yet people leave behind plenty of information that’s never written down. Societies that don’t use written language have preserved complex and detailed information orally for centuries. That’s how someone like Tupaia—and Mau Piailug—had mental maps covering thousands of miles of open ocean.

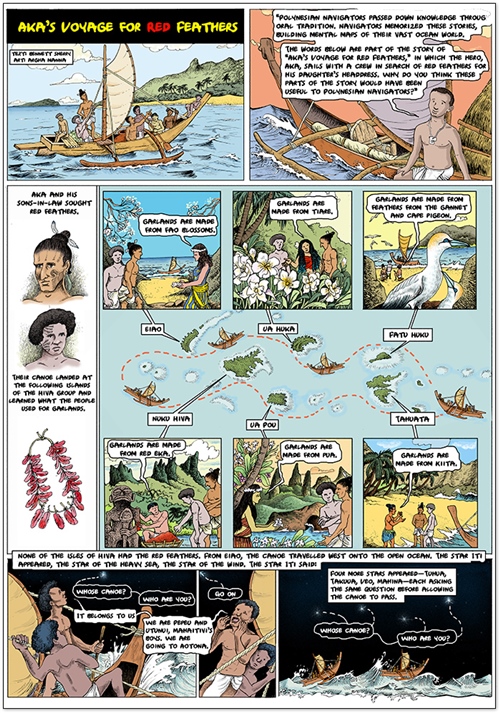

Stories were at the heart of this remarkable example of collective learning. For example, Mau’s graphic biography is accompanied by a graphic primary source: the story of “Aka’s Voyage for Red Feathers.” This story is one among countless myths, legends, and histories passed down by generations of mariners in Oceania (this abridged version comes from an early-twentieth-century transcription by E.S. Craighill).

“Aka’s Voyage for Red Feathers”—graphic primary source. Click to enlarge. By OER Project, CC BY-NC 4.0.

“Aka’s Voyage for Red Feathers”—graphic primary source. Click to enlarge. By OER Project, CC BY-NC 4.0.

Your students might notice that this story served more than one purpose. Sure, it was entertaining to the people who told and listened to it. But there’s important information embedded here. The story contains a list of islands in their geographical order. It lists the types of trade goods to be found at each island. And it contains the names and sequence of several stars that a mariner could use to navigate on open ocean, away from archipelagos. Stories are easier to remember than lists, and because Aka’s story featured a culturally relevant mythical hero, it was more likely to be passed down through generations, along with the information contained in it. These stories—and wayfinding techniques—proved resilient enough to survive centuries of colonial violence and erasure.

Shaping the future

How does this knowledge matter today? Well, for historians, it helps us better understand one of the greatest human migrations the world has ever seen. And for many Hawaiians and other Polynesians, it’s proof of their ancestors’ ingenuity and tenacity.

From Mau Piailug’s teachings, an entire wayfinding tradition has been rebuilt. Today, the Polynesian Voyaging Society continues to train new generations of navigators, and the Hōkūle‘a has sailed over 140,000 nautical miles to ports around the Pacific.

You might ask your students why stories like Aka’s would have been useful for navigators like Mau. Once they’ve figured that out, ask them for some examples of stories that they know and have them tease out what information was passed down through them (for example: “Red Riding Hood” warns children to be skeptical of strangers). Finally, your class might create a story or song of their own, designed to orally pass on information to next year’s class. Maybe a cautionary tale about the dangers of skipping class, or a parable that contains directions from the gym to the cafeteria.

A teacher appeared from the art room and said,

“Whose hall pass is this?”

“It belongs to us. We are Olivia and Jackson, from homeroom.”

“Go on.”

About the author: Bennett Sherry holds a PhD in history from the University of Pittsburgh and has undergraduate teaching experience in world history, human rights, and the Middle East. Bennett writes about refugees and international organizations in the twentieth century. He is one of the historians working on OER Project courses.

Cover photo: Composite image: Mau Piailug enjoys tributes and thanks for his reintroducing the art of noninstrument navigation to Hawaiians during a 2006 ceremony. "Papa Mau", from the Micronesian island of Satawal, was a key to the renaissance of Hawaiian canoe voyaging, guiding the 1976 Hawaii-Tahiti voyage. © lvis Upitis/Getty Images. Mopographic map. The stylized height of the topographic contour in lines and contours. © Oleksandr Hruts / iStock / Getty Images. Gradient abstract constellation background. © Freepik.

Image 2: Growth chart stock photo, © alexsl / E+ / Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

-

Erin Cunningham

-

Cancel

-

Up

0

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Comment-

Erin Cunningham

-

Cancel

-

Up

0

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Children