By Rachel Phillips

OER Project Learning Scientist

If someone asked you, “What does teaching mean to you?” how would you respond? Perhaps with a somewhat vague response—it is, after all, an incredibly open-ended question. However, if you were asked, “What does teaching mean to you now versus what it meant at the start of your career?” you might be able to get a bit more concrete. That’s because the second question asks you to compare two givens, rather than come up with an idea in isolation.

Comparison is something everyone does naturally from a very young age. And as it turns out, comparison is a key skill for learning. It’s simple, and it’s also great for introducing new ideas and gaining deep understanding of any subject. Consider something you know nothing about. For me, a good example is skateboards. If someone showed me a skateboard and asked me to point out the important features of it, I wouldn’t be able to come up with much more than wheels and a top. However, if someone showed me two different skateboards, I might notice differences in the size of the two tops, in the ways the wheels are attached to each of the boards (apparently called “trucks”), as well as differences in the wheels themselves. The idea is this: If you see one instance of something unfamiliar, something that you don’t know a ton about, it’s difficult to pick out the important features. But if you see two different versions of that unfamiliar thing, you can start comparing and contrasting. The learning sciences call this contrasting cases, and studies show that contrasting cases helps us not only learn new things but learn them so well that we can apply what we’ve learned. That’s called transfer, which is one of the most powerful ways to validate that something has been learned with understanding.

Left: Women’s march to Versailles, October 1789. © Getty Images. Right: Women marching during the Russian Revolution, demanding the right to vote, October 1917. © Getty Images.

So, how does this apply to historical comparison? Well—and I’m sure this will come as a shock to you—our students don’t always know a lot about the past. Giving them the opportunity to compare similar types of historical events helps students retain information more easily and helps them understand the nuances of different, yet similar, events. For example, instead of teaching about one revolution at a time, it’s better to have students compare different revolutions so they can see how revolutions start, evolve, and then what might happen post-revolution. By doing this, your students will find traits that revolutions have in common, and other traits that are unique to each. Those common things will often point to the underlying characteristics or structures that make something what it is, such as the strengths and weaknesses of empires. Understanding underlying characteristics is what leads to deep understanding and the ability to transfer. It’s also a faster and more efficient way to learn. And given how much content students have to learn these days, the more we can combine and conquer, the better off we’ll be.

While this seems pretty straightforward, when you’re asking your students to engage in historical comparison, it’s important to consider how you will structure these activities to maximize student learning. There’s another learning science principle, called a time for telling, which emerged from studies that examined the ideal time for teachers to explain concepts to students. Turns out, if you allow students to engage in comparison before you explain concepts, they’re much more likely to learn and remember those concepts. For example, imagine you want students to understand population growth at two different times in history. The traditional approach might be to give a mini-lesson and then provide some data in the form of charts or graphs for students to analyze. Studies show that in this setup, students are less likely to be able to connect what they learned to the data they’re analyzing. However, if you give students two charts or graphs that show population growth to compare and contrast before the mini-lesson, they’ll have prior knowledge to use and with which to make connections in the mini-lesson. In short, students are encouraged to cognitively engage with the material, which helps them build a schema around what they’re trying to learn, and then when they sit in a lecture, read an article, or watch a video, what they have come to the table with can be supported, extended, or challenged by the new information they’re being presented with. This is actually why the flipped classroom model hasn’t been as effective for learning as people originally thought it might be—students are given the information first, then asked to practice, and the two things often end up seeming disconnected.

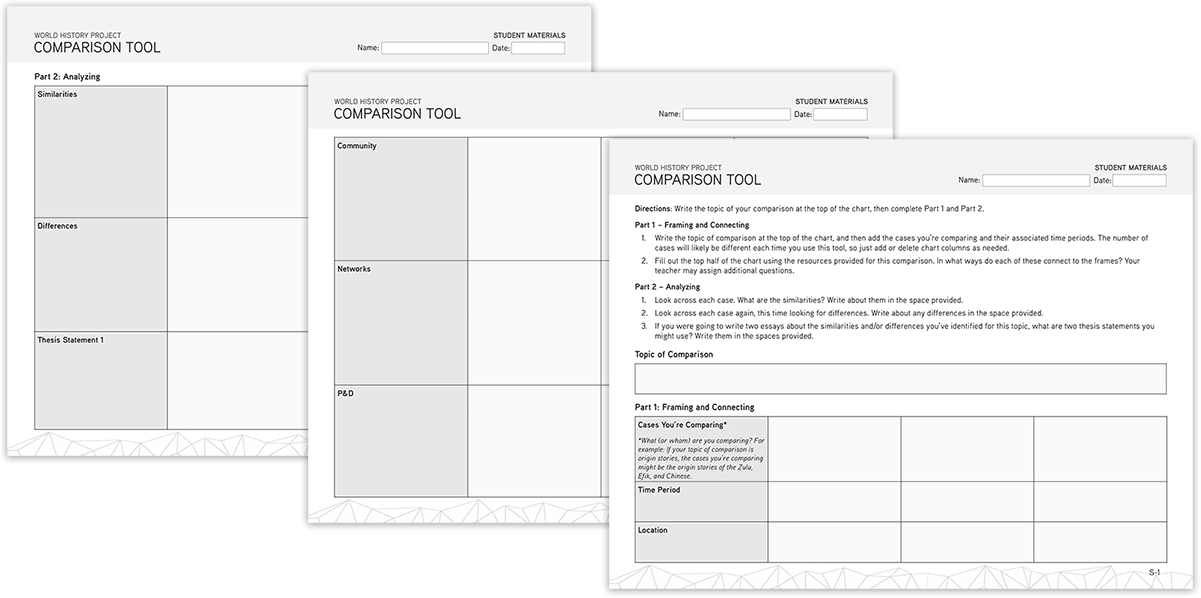

World History Project Comparison Tool.

World History Project Comparison Tool.

Bottom line—comparison is a powerful tool to use in the classroom. And because it can be simple, it may often be de-emphasized in favor of hard-to-learn skills such as causation or continuity and change over time. We encourage you to use comparison and use it often—not only is it a powerful way to learn with understanding, but it also allows you to cover a lot of content at one time. As we know, history keeps getting longer and content standards just keep growing, so we need all the strategies we can find to learn efficiently, effectively, and deeply.

About the author: Rachel Phillips, PhD, is a learning scientist who leads research and evaluation efforts for the OER Project, and also develops curricula for their courses. She is elementary certified, has taught in K–12 schools, and currently serves as an adjunct professor for graduate courses in American University's School of Education. Rachel was formerly Director of Research and Evaluation at Code.org, faculty at the University of Washington, and program director for National Science Foundation-funded research. Her work focuses on the intersections of learning sciences and equity in formal educational spaces.

Cover image: Composite image of girls sitting on skateboards along rural road, Portland, Oregon, USA. © Image Source / Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments