By Trevor Getz, OER Project Team

San Francisco, USA

We all know students need to learn to contextualize

Contextualization fits in everybody’s list of core historical skills. No, really! It’s hard to find anybody who doesn’t call for students to learn how to, in the words of the AP World History Course and Exam Description, “analyze the context of historical events, developments, or processes.”[1] Similarly, the first History Discipline Core Competency listed by the American Historical Association (AHA) is for students to “gather and contextualize information in order to convey both the particularity of past lives and the scale of human experience.”[2]

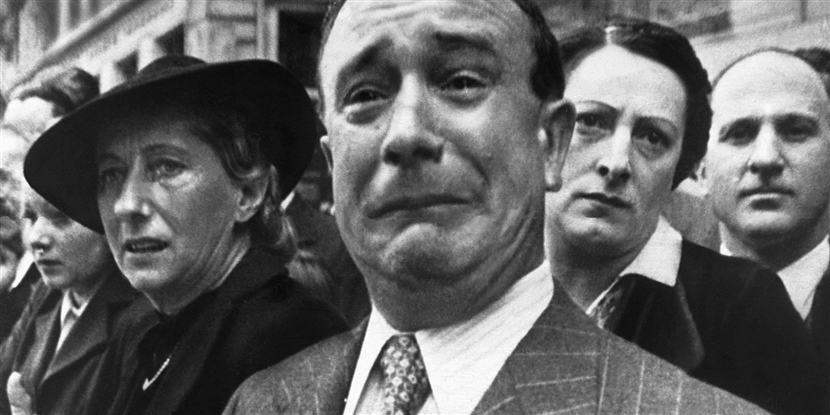

And so, dutifully, we who teach history instruct students on the important components of contextualizing the material they work with. Mostly, we teach contextualization as part of the skill of reading a document. We want students to understand that a primary source is a part of a whole. It can be read and understood adequately only when you understand where it comes from and whom it is for. In the introductory activity for learning contextualization in OER Project’s World History—1750 to the Present course, for example, we ask students to analyze a picture of a crying man with no additional information. We ask, “Why is this man crying?” Typically, students have few answers until their teacher gives them more context: the time frame (1940), the location (France), and some additional clues to the events happening at that moment (the German occupation of France).

Analyzing a particular photograph, or an official record, or a letter, is of course very important. It helps students develop a skill they’ll need in life: The ability to encounter a piece of evidence and understand its meaning based on its environment. Whether they’re perusing a document on the job, reading a letter from a friend, or watching a cult classic movie, they must understand context.

But go back and read those statements from the AP description and the AHA again. They’re not just asking that we teach students to learn how to analyze a historical document or source. They’re calling for students to learn to analyze the context of “events, developments, or processes” and to understand not just “past lives” but also “the scale of human experience.”

Contextualizing the big stuff

In other words, students also need to learn how to contextualize “the big stuff.” They need to know that events like the hajj of Mansa Musa, the wealthiest man in world history, were made possible by political transformations in twelfth- and thirteenth-century West Africa, the importation of camels from Arabia, and economic and religious connections made possible by Islam across a vast region of Afro-Eurasia—to name just a few contextualizing factors!

Students can also benefit by contextualizing the really big stuff, which in the Big History Project (BHP) means thresholds of increasing complexity, and in the World History Project means the frames.

Let’s start with Big History’s Threshold 7—Agriculture. As the BHP materials tell students, for most of human history, all humans foraged for food. Then, around 11,000 years ago, humans in several locations learned to farm. And so began a long shift from foraging to farming, which is the main way we get our food today. Understanding this shift requires contextualizing on a global level, something that we do really well in BHP. Throughout this unit, students learn about the conditions and ingredients that made this shift possible: the increasing density of human communities; ways in which human understanding of our environment had already shifted; climate warming; and increasing competition for resources. To some degree, students also get to work in smaller scales. We talk more about these local contexts in the World History Project courses, where students explore the particular experiences of agrarian societies in China; Egypt and Nubia; Mesoamerica; Aksum (northeast Africa); Nok (West Africa); and the Indus River Valley. We also try to use these local contexts to complicate the dominant narrative about the switch to farming. In particular, we feature two graphic biographies—the “Eloquent Peasant” from Egypt and the “Xianrendang Pottery” from China.

In the World History Project, “the big stuff” mostly comes in the form of the frames: networks, communities, and production and distribution. We want students to use the frames to contextualize both the sudden transformations and those that took place over longer periods. So, for example, let’s look at the production and distribution frame. We try to help students contextualize the big changes that support the narrative of overall economic growth in human history, such as the shift to agriculture and the Industrial Revolution. Our contextualization activity How Was Industrialization Possible? asks students to determine the global and local contexts for the first real industrialization, in eighteenth-century Great Britain. But we also ask students to contextualize the moments that bring this narrative of continual growth and progress into question, like the Great Depression.

Contextualizing thresholds and frames can help students, just as contextualizing documents and images can. The process is a bit different, but the lesson is the same: To understand what’s going on, you have to relate the part to the whole. You must understand that what you’re studying is an element in a vast, complex, system of interlocked people, experiences, and histories. It’s an important lesson in any student’s journey in learning to think like a historian!

[1] College Board, “AP World History Modern Course and Exam Description, Effective Fall 2019,” 14.

[2] American Historical Association, Core Competencies and Learning Outcomes, 2016.

About the author: Trevor Getz is professor of African and world history at San Francisco State University. He has written or edited 11 books, including the award-winning graphic history Abina and the Important Men, and coproduced several prize-winning documentaries. He is also the author of A Primer for Teaching African History, which explores questions about how we should teach the history of Africa in high school and university classes.

Cover image: A man weeps as historic French battle flags are taken out of Marseille for safekeeping in 1941. © CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments