By Rachel Phillips, OER Project Learning Scientist

Theodore Roosevelt is credited with saying that “comparison is the thief of joy,” and in many ways, he’s right—the grass does often seem greener on the other side. However, if Roosevelt had been talking about historical comparison, he couldn’t have been more wrong. Historical comparison brings joy to historians, and I’m going to gamble and say that it’s even possible for historical comparison to bring joy to history students. And it’s not because comparison is one of those “easy” skills. Yes, we compare all the time in everyday life; making comparisons is something we gravitate toward naturally, and studies using fMRI machines show that babies as young as 15 weeks can compare two things and show a preference for one over another. It’s just part of the fabric of life.

But how is it the fabric of history? Well, without comparison, it’s pretty difficult to construct a historical narrative. If we don’t look at how things are similar, and how they differ, how do we pick out the distinguishing features of each or tell stories about this versus that? The answer: not very well. Historians use comparison frequently, and we can probably assume it’s fun for them—they do love history after all! However, just because it’s fun for historians doesn’t automatically make it fun or joyful for students. So, how can do we add the fun to comparison? By giving students both voice and choice. Research proves that listening to students and allowing choice is one of the keys to engagement in school, which of course enhances learning.

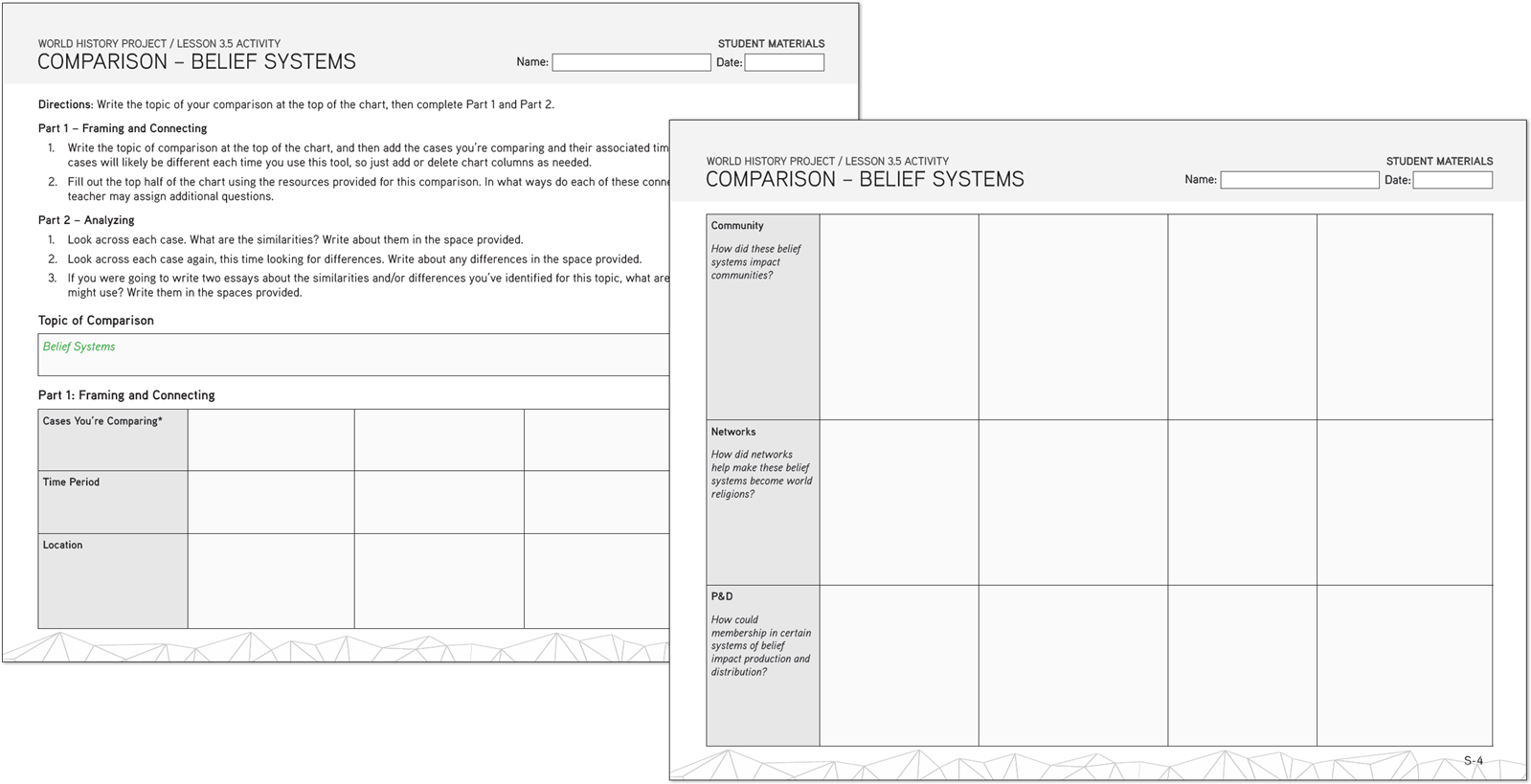

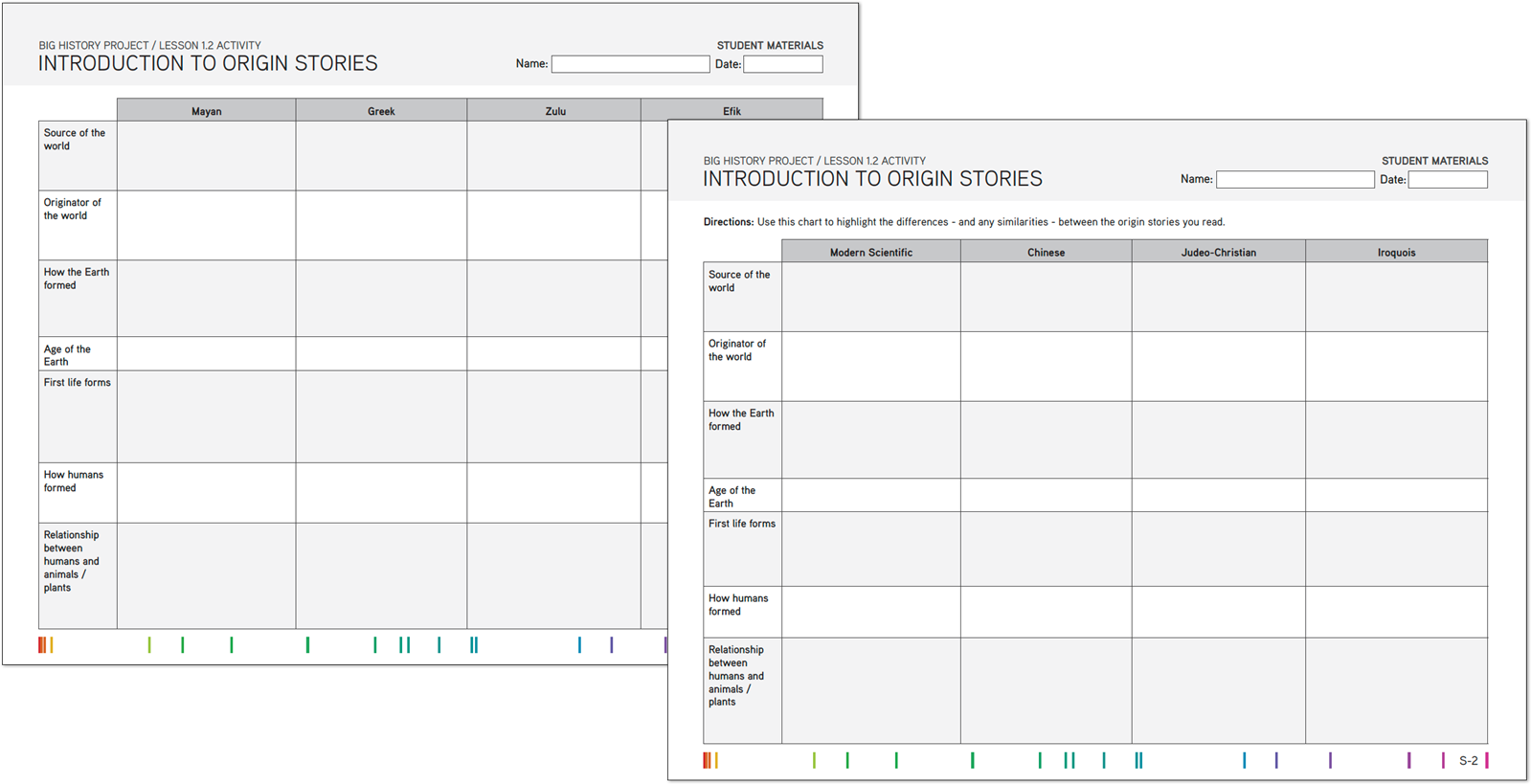

When it comes to historical comparison, the fact is we usually tell students what to compare, and we even tell them how to compare it by giving them specific criteria upon which to make those comparisons. This is a sound approach, one often used in OER Project activities. Take for example the structured comparative work that’s part of World History Project’s comparison practice progression. Or, in the Big History Project course, the activity in which we compare Origin Stories and complex societies. However, neither of these otherwise excellent activities really put students in the driver’s seat for doing this kind of historical work.

WHP’s Comparison – Belief Systems

BHP’s Introduction to Origin Stories

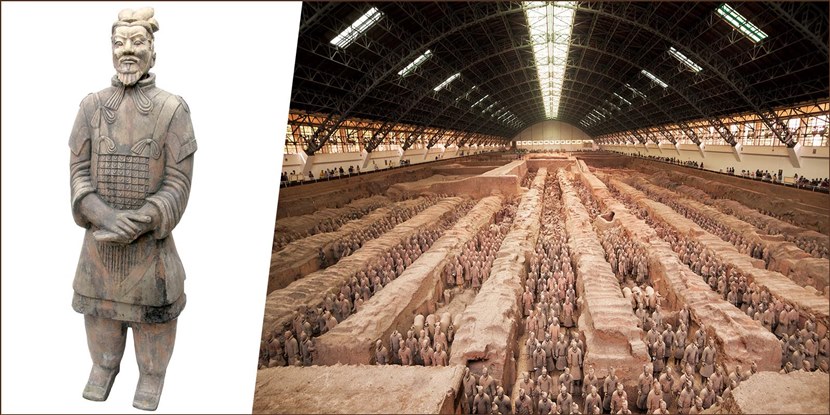

To bring some fun, joy, and even equity into the practice of comparison, why not let the students choose what they want to compare, or even the criteria they want to use to make a comparison? In WHP, this could look like students coming up with a new frame or two to use as the criteria for comparison. Or in BHP, this could occur when learning about scale—for example, what happens if you’re on Rapa Nui (Easter Island) and you zoom in on one Moai statue, but then zoom out and see them all? Or, to use an example not found in our courses, what happens if you zoom in on one warrior in the Qin Dynasty Terracotta Army and then zoom out and see the entire army? Or, what if you compare a historical person at the point of their greatest renown to that person at other points in their life? Or, you might even have students compare their current selves to their former selves. I guarantee, students will be a lot more creative in finding comparisons that may seem more unusual than your typical social studies comparisons and will undoubtedly highlight ways to think differently about the past. In doing this, students will truly take on the role of historian, finding new narratives and new ways of thinking about and analyzing the past.

Giving students the opportunity to do historical comparison without dictating what or how they compare also allows student empowerment. It shows them that the historical record is not set in stone, and by comparing like historians, ones with fresh perspectives, they are likely to diversify and deepen their own historical knowledge. Providing new ways to analyze history allows your students to get creative, to bring their own perspectives and voices to the table, and to show there are many paths to being successful historians. By doing this and allowing students a chance to examine history from new angles, you—and they—will likely bring more fun and joy into the process.

If you’ve turned the comparison reins over to your students, how did you do it and what was the outcome? Please join us in the OER Project Teacher Community to share your ideas for letting students drive the comparison bus!

About the author: Rachel Phillips, PhD, is a learning scientist who leads research and evaluation efforts for the OER Project, as well as develops curriculum for their courses. She is elementary certified, has taught in K–12 schools, and currently serves as an adjunct professor for graduate courses in American University's School of Education. Rachel was formerly Director of Research and Evaluation at Code.org, faculty at the University of Washington, and program director for National Science Foundation-funded research. Her work focuses on the intersections of learning sciences and equity in formal educational spaces.

Cover images: Composite image of the terracotta army of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China, dates from 210 B.C. in Xian, China. A single warrior © OliverChilds / E+ / Getty Images (left) and the whole army © MediaProduction / E+ / Getty Images (right).

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,