By Bennett Sherry, OER Project Team

“What are we gonna learn this year?” As we stare into the abyss of a new school year, it can be a thrilling—and scary—question. One of the key learning objectives for Big History Project (BHP) and World History Project (WHP) students is understanding that the history and scientific discoveries they’re learning this year exist thanks to the contributions of many people over thousands of years. Sir Isaac Newton famously called this “standing on the shoulders of giants.” In both BHP and WHP, we call it “collective learning.”

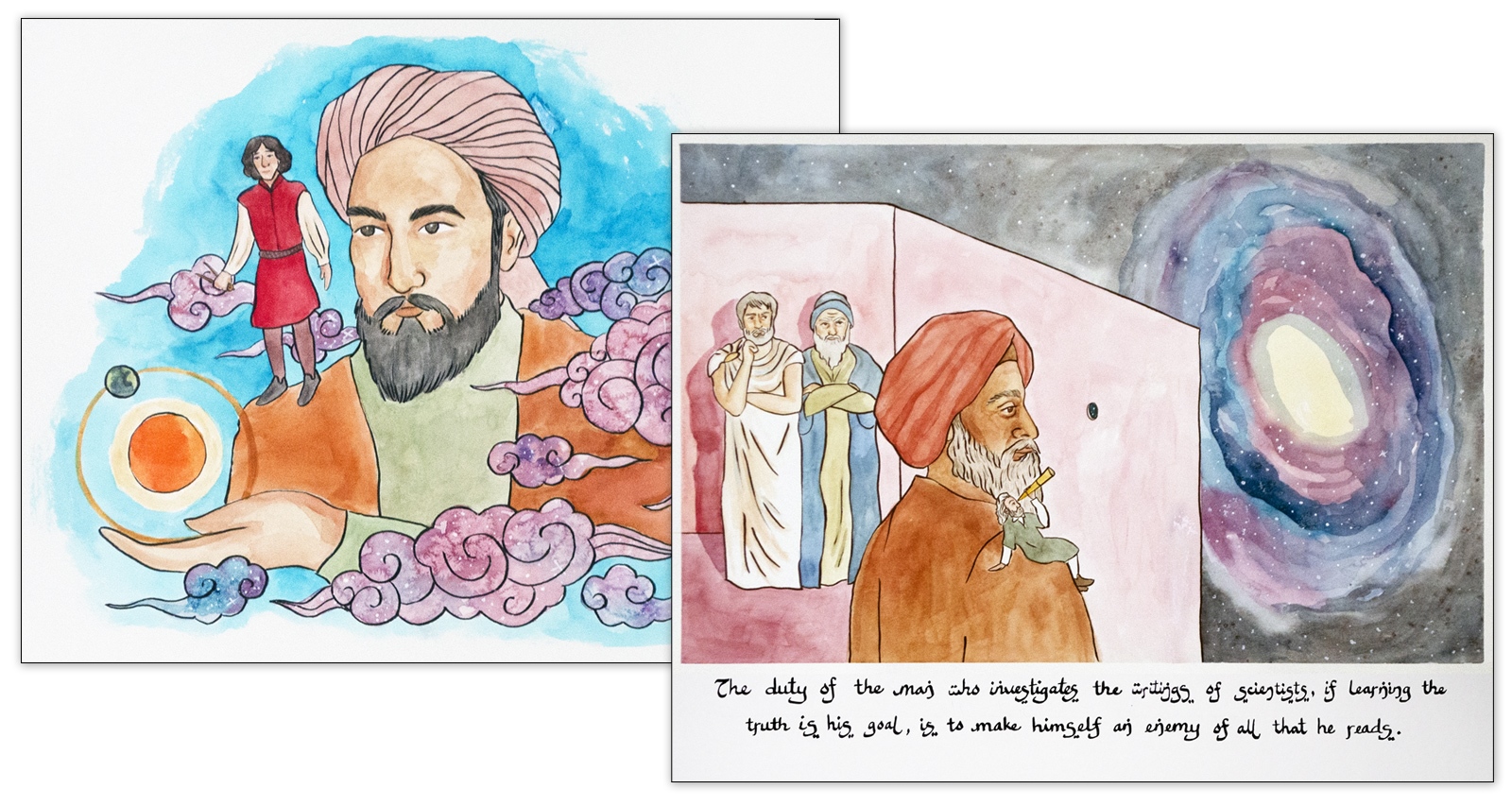

BHP articles about collective learning, Standing on the Shoulders of Invisible Giants (left) and The Universe Through a Pinhole: Hasan Ibn al-Haytham (right).

BHP articles about collective learning, Standing on the Shoulders of Invisible Giants (left) and The Universe Through a Pinhole: Hasan Ibn al-Haytham (right).

Last year, we introduced a new series of illustrated articles about Islamic scholars to BHP. As your students encounter “invisible giants” such as Ibn Al Haytham and Ibn Majid, they will see that much of the knowledge we depend on today was built on the work of scholars they’ve never heard of. Like many people from many different places, these Islamic scholars contributed to creating the knowledge that produced our modern scientific origin story. From a vast nothingness to a Universe full of stars, galaxies, and us, this origin story is incredibly complex, and it was composed through the work of many different people, each building on the work of those who came before.

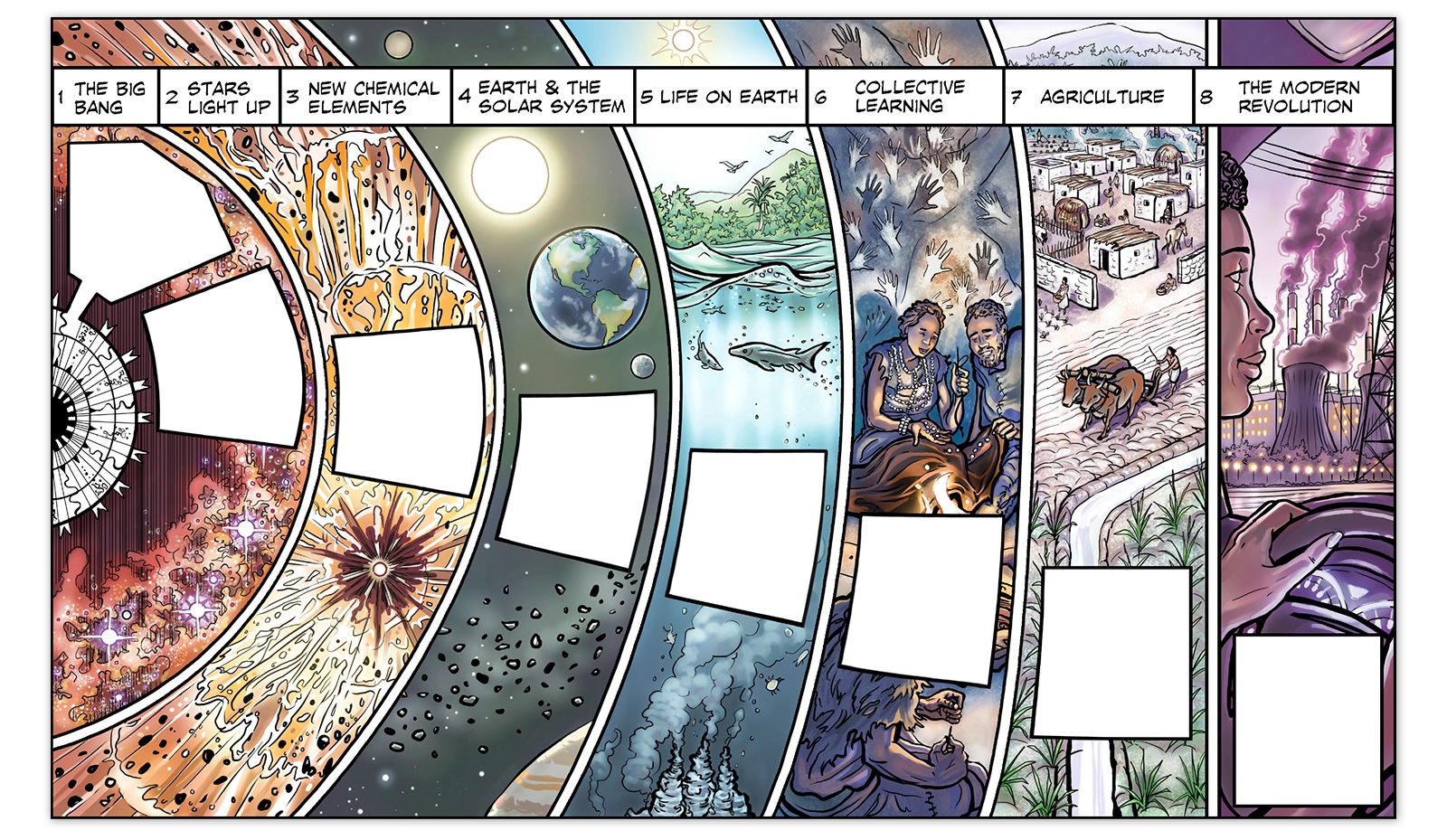

BHP’s eight thresholds help organize our modern origin story.

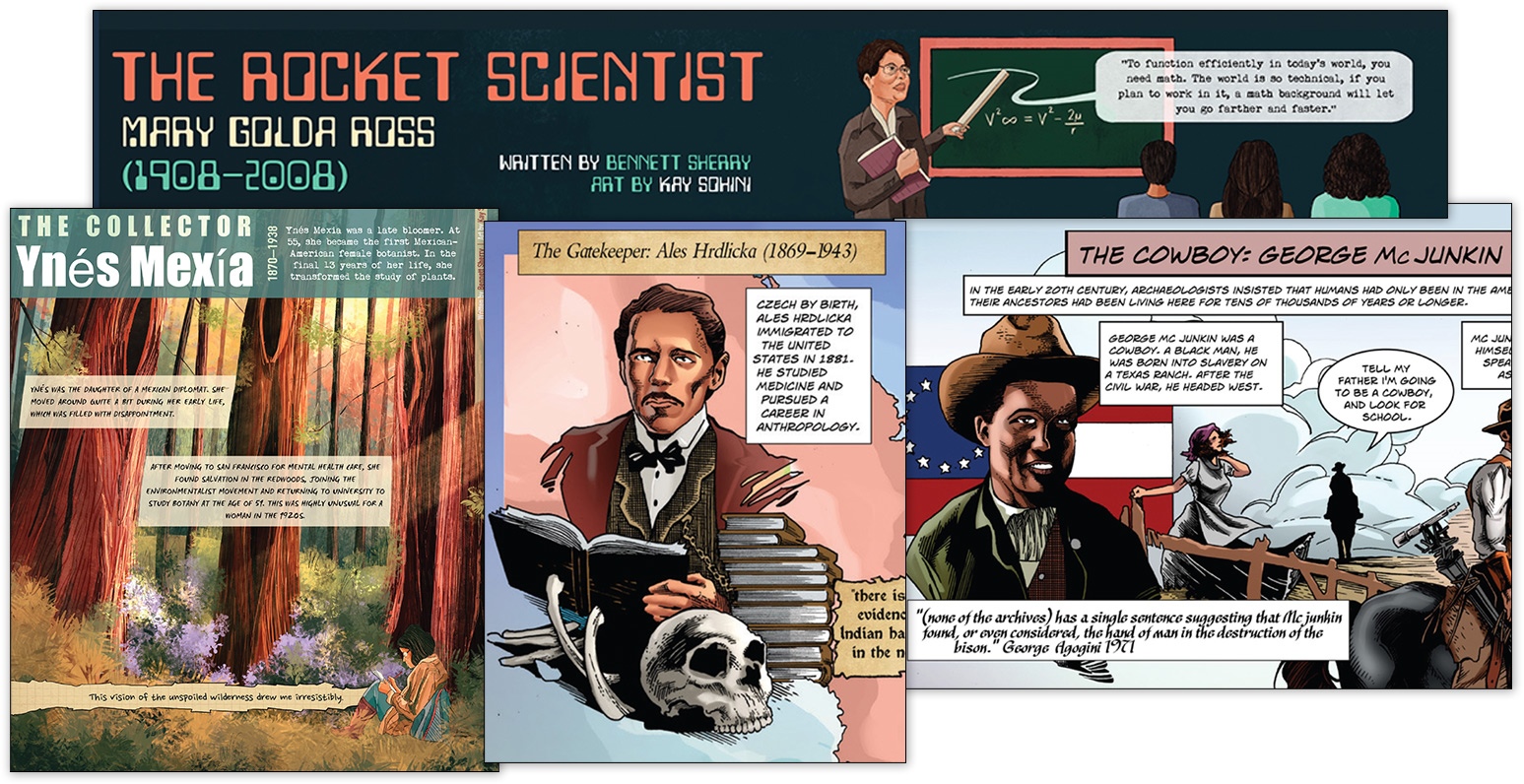

Both Big History and world history are, well, big! They include the history of planets, stars, and the whole of humanity. But both the history of the world and the history of the Universe also made up of smaller stories: The stories of individual people pressing our knowledge forward. Full of breakthroughs and mistakes, heroes and villains. The story of who we are and how we got here is a mosaic of the lives and work of brilliant scientists and geniuses, but also the lives and work of everyday people—cowboys, sailors, botanists, and milkmaids. To continue the search for the invisible authors of our modern origin story, we’re introducing new graphic biographies for BHP in the vein of the graphic biographies that accompany all WHP courses. During the year, we’ll be releasing these one-page comics that tell some lesser-known stories, stories of people who contributed to the long history of collective learning that produced our modern origin story.

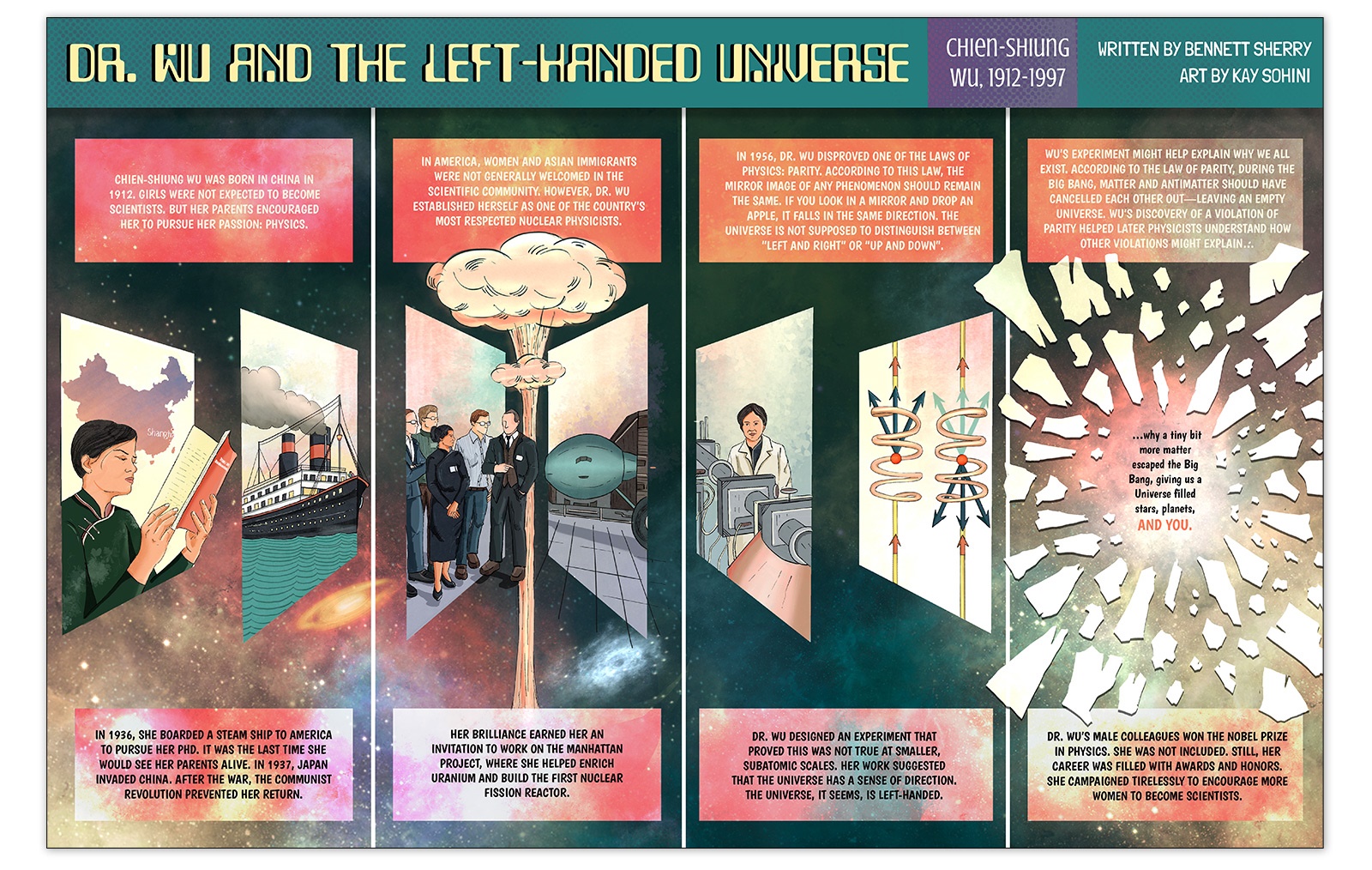

Some pretty impressive geniuses have been invisible in the history of science as well. Let’s take an example: I bet your students know the name Albert Einstein. If they’re excited about astronomy, physics, or extraterrestrials, they might also know names like Fermi, Hubble, Oppenheimer, and Curie. But do they know Chien-Shiung Wu? I’m guessing most don’t. And that’s despite the fact that her experiments launched a chain of collective learning that helped explain why anything exists at all. Why our Universe—stars and nebulae, blackholes and labradoodles, Harry Styles and hydrogen, anything with matter—exists at all.

Why is there something rather than nothing? According to the laws of physics, the Big Bang should have produced equal amounts of matter and anti-matter, which would have canceled each other out, leaving nothing but an empty Universe filled with leftover energy. Recently, physicists have begun to unravel this mystery, discovering violations of natural laws that might have permitted the tiniest surplus of matter—about one part in a billion—to escape the Big Bang intact. That matter is what you, and I, and all those stars, and labradoodles, and everything else, is made of.

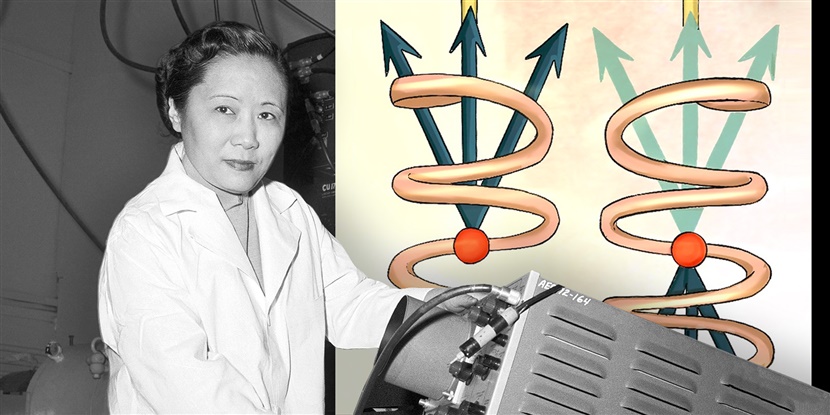

Just as unlikely as our existence was the career of Chien-Shiung Wu, who is today remembered as the “First Lady of Physics.” A Chinese immigrant to America and a woman, Dr. Wu overcame many barriers on her path to becoming the world’s leading expert on beta decay. She is one of the most important physicists of the twentieth century. You can learn more about Dr. Wu and her most famous experiment in this graphic biography.

Dr. Wu and the Left-Handed Universe: Chien-Shiung Wu graphic biography.

Dr. Wu and the Left-Handed Universe: Chien-Shiung Wu graphic biography.

In addition to her many other contributions to nuclear physics, Dr. Wu’s work paved the way for later physicists to begin to understand how matter might have escaped the Big Bang. But Wu contributed to collective learning in other ways. Like many of the women and people of color in these graphic biographies, Dr. Wu paid it forward. She campaigned tirelessly to get more women involved in the sciences. Speaking at MIT in 1964, she reflected, “I wonder whether the tiny atoms and nuclei, or the mathematical symbols, or the DNA molecules have any preference for either masculine or feminine treatment.”

In these graphic biographies, we tell Dr. Wu’s story and those of many others who contributed to the long chain of collective learning that produced the modern origin story at the heart of BHP.

The stories in the Islamic Scholars collection and in these new graphic biographies remind us that the development of our modern scientific origin story started long before the Scientific Revolution and involved all sorts of people from all over the world. And it’s a story that we’re still telling today, revising with each new experiment and each new observation. Some of these stories feature scientific ideas we still accept today. Others explore ideas that have been debunked. But our mistakes and failures are a part of this story, as much as our triumphs. These resources help students grapple with the idea that scientific knowledge doesn’t simply exist—it is developed and refined over time, through experimentation, mistakes, and cross-cultural exchange.

Whether in BHP or WHP, your students are going to learn a whole lot this year. In BHP, they’ll examine the modern origin story as they uncover more about the history of science. In WHP, they’ll explore developments like the Islamic Golden Age, the Enlightenment, and the Industrial Revolution. In both courses, they’ll encounter big narratives, including the seven thresholds and three frames. And they will use graphic biographies to challenge and revise these narratives as they learn about some of the many individuals who played a role in shaping them. But remember to remind your students—maybe as new photos from the James Webb telescope trickle back to us—that there is a whole lot we still don’t know, and we’re counting on them to keep learning.

About the author: Bennett Sherry holds a PhD in history from the University of Pittsburgh and has undergraduate teaching experience in world history, human rights, and the Middle East. Bennett writes about refugees and international organizations in the twentieth century. He is one of the historians working on the OER Project courses.

Cover image: Composite image. Physics Professor Dr Chien-Shiung Wu in a laboratory at Columbia University. © Bettmann / Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,