By Bennett Sherry, OER Project Team

Each year around November 1, hundreds of thousands of people gather in Mexico City for a huge parade in celebration of Día de los Muertos—the Day of the Dead. Or at least, they have every year since 2016.

You see, in 2015, the James Bond film Spectre was filmed in Mexico City. During the opening scene, Daniel Craig battled through a crowded parade as revelers in skull masks and colorful costumes marched to celebrate the Day of the Dead. There’s just one problem: Mexico City didn’t have any such parade. Yet to capitalize on the popularity of this film (and others, like Disney’s Coco), the city government started hosting an annual parade in 2016. Over 250,000 people attended, and that’s how the “tradition” of an annual parade started!

In our deeply interconnected, globalized world, this sort of cultural phenomenon isn’t uncommon. A cultural tradition in one place becomes popular in another and changes in the new place. But then, somehow—through a movie, travel, or some other means—it comes back to the place of origin and changes the original tradition. Take pizza, for example. It started out as a simple Italian flatbread and stayed that way in Italy, even as it turned into a cheesy, saucy vehicle for toppings in the United States. But later, when Italian American migrants visited family in Italy in the early twentieth century, they brought along the American take on pizza, with all its toppings. Pizza in Italy was changed forever.

Daniel Craig, as James Bond, is seen on the set of "Spectre" in 2015 in Mexico City, Mexico. © Clasos/GC Images/Getty Images.

Daniel Craig, as James Bond, is seen on the set of "Spectre" in 2015 in Mexico City, Mexico. © Clasos/GC Images/Getty Images.

The history of Día de los Muertos predates James Bond by a few thousand years, and it’s filled with a variety of changes and influences that crossed oceans and defied empires. The holiday blends elements of precolonial Indigenous practices, Catholic rituals, and ideas from pre-Christian Iberia. If you’re teaching Era 3 of WHP Origins, Unit 3 of the 1200 course, Unit 4 of the AP course, or BHP Unit 7, Día de los Muertos offers a great example to illustrate cultural syncretism.

These days—in addition to the new parade—the celebration of the Day of the Dead takes place on November 1 and 2. Specific traditions vary from place to place, but generally communities gather in cemeteries to clean family tombs, leave treats for their deceased family members, and celebrate their memory. Sugar skulls (calaveras), special bread (pan de muerto), marigolds, and are among the offerings left for the dead. Alcohol consumption is common, and the festivities are joyous and unburdened by mourning. It's believed that on this day, dead relatives awake from their sleep to party with you, so you wouldn’t want to offend them by being morose. But beware! If you fail to remember your dead kin, punishment awaits you in the afterlife!

Each celebration is based on rituals repeated year after year. But where do these rituals come from? Are they indigenous? Spanish? Or brought from even further away? Probably all of these! In fact, this a great example of cultural syncretism. However, it’s pretty tough to trace the many routes through which cultures form—whether in Central Asia or surrounding the Lady of Guadalupe. So as you cover the origins of traditions, make sure your students have their claim testers!

The traditions behind the Day of the Dead didn’t emerge from any single place but rather from a long history of cultural blending. Many historians argue that the festivities are inspired by Indigenous Mesoamerican traditions, particularly the Nahua people who lived in the Aztec Empire. Their celebrations of the dead included offerings of food to aid the deceased on their journey. Typically, these celebrations were held in the summer months. The Aztec Empire, of course, conquered many peoples, and it’s likely that these early festivities were a blend of earlier traditions.

After the Spanish conquests of Mesoamerica, the colonizers brough Catholicism to the Americas. Catholic missionaries and colonial missionaries saw the persistence of Indigenous religion as a threat and sought to quash earlier practices. When this failed (as it often did), the new Catholic practices sometimes blended with Indigenous traditions to create something new. But Day of the Dead celebrations also might have been influenced by other, non-Christian traditions from the other side of the Atlantic. Some scholars note similarities to various European and Iberian folk traditions, such as the Danse Macabre. Others point out that, given the long history of enslavement in Mexico, West African influences are also likely.

During the colonial period, the Spanish worked to move the celebrations from the summer to early November, so it would coincide with the Catholic special masses of All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day. At other times, colonial officials took steps to repress the celebrations, either by banning visits to cemeteries or limiting the sale of alcohol. It appears that continued celebration of the Day of the Dead was, at least in part, a form of resistance against the Spanish colonial government.

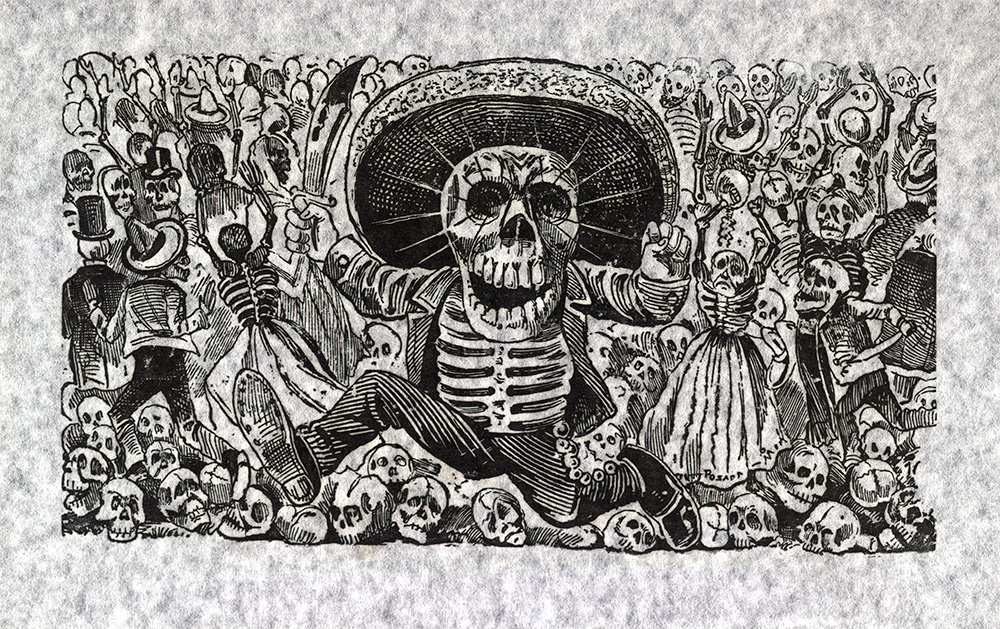

Day of the Dead continued to stand as a symbol of resistance into the twentieth century. The sugar skulls that we associate with this holiday today are thanks to the artist Jose Guadalupe Posada. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Posada drew a huge number of satirical broadside illustrations criticizing elites in Mexico, continuing his work through the early years of the Mexican Revolution.

Calavera Oaxaquena, published by Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, circa 1903. Print shows fierce calavera brandishing knife with a crowd of calaveras behind him. © VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images.

Calavera Oaxaquena, published by Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, circa 1903. Print shows fierce calavera brandishing knife with a crowd of calaveras behind him. © VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images.

As you introduce syncretism, you might show your students a picture or two from the celebrations, like the one below. Ask them to do some research and label the picture, identifying elements that they think came from Indigenous, Christian, or other sources. They might be surprised how hard it is to tease apart one from the other. Then you might ask them what James Bond has to do with this Mexican holiday! Popular culture changing a centuries-old cultural practice in such a dramatic way is a great reminder that cultures are not static. And our traditions continue to evolve as our societies grow more interconnected.

Dia de los Muertos altar on display at the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City, Mexico. This altar is dedicated as reverence to Our Lady of Guadalupe and remembrance of deceased love ones. © Gabriel Perez/Moment/Getty Images.

Dia de los Muertos altar on display at the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City, Mexico. This altar is dedicated as reverence to Our Lady of Guadalupe and remembrance of deceased love ones. © Gabriel Perez/Moment/Getty Images.

About the author: Bennett Sherry holds a PhD in history from the University of Pittsburgh and has undergraduate teaching experience in world history, human rights, and the Middle East. Bennett writes about refugees and international organizations in the twentieth century. He is one of the historians working on the OER Project courses.

Cover image: Participants in traditional costume and with their faces painted seen during the Catrina Festival. Thousands of people took to the streets of Mexico City to watch the procession of Catrinas. Catrina is a female skeleton with a large hat, often made of feathers. The figure is based on a character created in the early 1900s by artist José Guadalupe Posada and then reinvented by Diego Rivera. © Lexie Harrison-Cripps/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments

-

Joe Baginski

-

Cancel

-

Up

+1

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Comment-

Joe Baginski

-

Cancel

-

Up

+1

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Children