By Bridgette Byrd O’Connor, OER Project Team

At this point in the school year, you and your students may be about to embark on the history of the world wars or maybe even the Cold War. Both are pertinent topics this year, providing valuable background (and even possibly continuity) for the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the surrounding crisis of 2022. Those kinds of connections across time are an important feature of thinking historically. For example, the world wars are taught as two separate and distinct periods of global conflict, but here at the OER Project, we also ask students to consider what happens when we shift scales and discuss thirty years of continuous global conflict? Or, what if we broaden our view even wider and discuss the whole of the twentieth century through the lens of global conflict? In fact, broadening the periodization and looking at the twentieth century as an era of global conflict will help students understand the continuities and changes that have led to the current crisis.

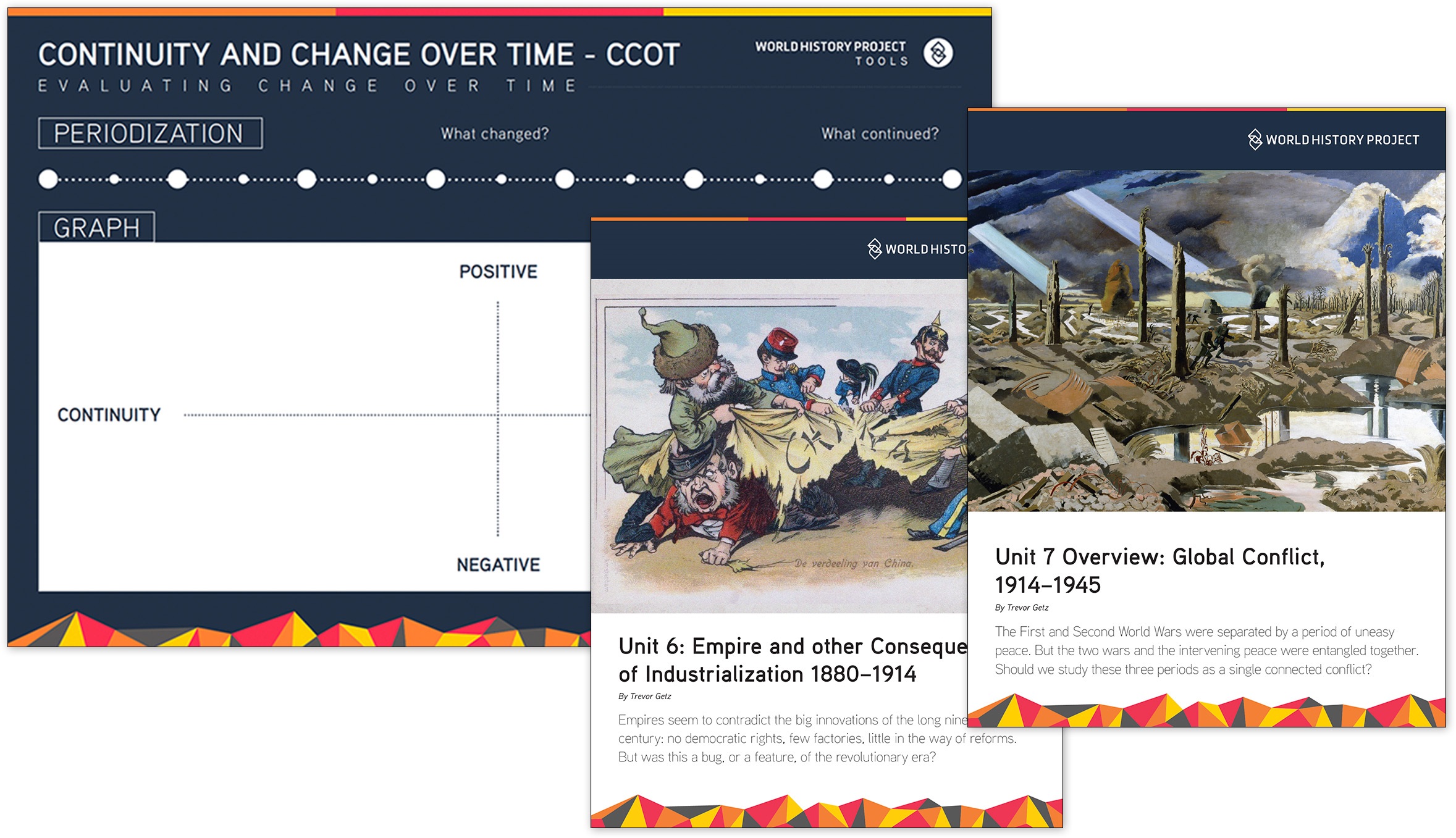

In order to evaluate the continuities and changes that occurred in the twentieth-century era of global conflict, students could use the WHP 1200 Unit 7 CCOT—Empire to Global Conflict activity. “CCOT,” of course, stands for continuity and change over time, and your students would benefit from exploration of continuities and changes even if they’re taking another WHP course “flavor.” The WHP 1200 Unit 6 and Unit 7 overview articles are a great way to get students thinking about continuity and change in the context of the transition from empire to global conflict, which sets the stage for the Cold War. This activity will allow students to think about how the vestiges of empire and decades of global conflict shape our world today.

The World History Project’s CCOT practice progression, which includes the CCOT Tool, asks students to create a list of changes and continuities over a set period of time, usually spanning two eras/units. From a student perspective, changes are often much easier to identify. For example, if discussing the transition from empire to global conflict, students might identify a new technology as a change. Innovations in weaponry, communication, and transportation during the long nineteenth century helped make the world wars deadlier and more global. They might also add that new independent states began to emerge as communities across the world started to demand freedom from colonial rule.

Continuities tend to be more difficult for students to determine than changes. However, the persistence of empires and the ongoing effects of industrialization are two that students can easily identify. You should be able to guide students to perceive how these continuities persist today. For example, Ukraine was part of both Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union. Pundits today speculate that Vladimir Putin’s ultimate goal is to reinstate Russian occupation of this region. Students might also note continuities in the form of industrial military technologies, like the tanks battling throughout eastern Ukraine in 2022, much as they did in 1942.

Once students have their list of changes and continuities, they can get to work in pairs or small groups. They choose the most significant changes and continuities for this era, categorize them using the WHP frames—or AP themes—and plot these on a graph. We ask students to consider if their most significant changes and continuities are positive or negative, or maybe somewhere in the middle, and then add them to the graph. Positive changes and continuities are placed above the continuum while negative ones fall below the line. But here’s the kicker—students will have to explain their reasoning using evidence from the era/unit, and if another group disagrees with the proposed location, they can change it, but only if they fully explain their reasoning with evidence.

CCOT poster with WHP 1200’s Unit 6 and Unit 7 overview articles.

This very simple act of placing sticky notes on a chart can quickly turn into an energetic debate about continuity and change over time. And you can quite easily extend this activity by asking students to plot the changes and continuities for current events like the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and use our Project X materials to explore related historical trends such as whether humans are fighting more or fewer wars now than in the past. You can also look at CCOT for other historical topics such as the Black Death or how we’ve come to live in the Anthropocene. It’s an engaging way to help students build a usable history by engaging with the challenges we face in the present using evidence from the past.

We’d love to hear the innovative methods you use to get students practicing continuity and change over time. Share your lessons in the OER Project Teacher Community or get inspired by conversations about CCOT such as this one, in which teachers shared CCOT ideas, or this one about facilitating a PD session on CCOT. You can also check out the blog post by Lynsey Woldendorp and Ben Tomlisson, the brains behind the CCOT Tool, along with numerous other CCOT teaching tips in this section of our on-demand, online professional development, Teaching World History.

About the author: Bridgette Byrd O’Connor holds a DPhil in history from the University of Oxford and taught the Big History Project and World History Project courses and AP US government and politics for 10 years at the high school level. She currently writes articles and activities for WHP and BHP. In addition, she has been a freelance writer and editor for the Crash Course World History and US History curricula.

Cover image: Flanders Soldiers. 5th October 1917: Supporting troops of the 1st Australian Division walking on a duckboard track near Hooge, in the Ypres Sector. They form a silhouette against the sky as they pass towards the front line to relieve their comrades, whose attack the day before won Broodseinde Ridge and deepened the Australian advance. © Frank Hurley/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments

-

Erin Cunningham

-

Cancel

-

Up

+1

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Comment-

Erin Cunningham

-

Cancel

-

Up

+1

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Children