By Michael G. Vann

Why did the Japanese Imperial Navy attack Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941? Many Americans thought—and many still think—it was the start of an invasion of the United States. Japan’s focus, however, was the invasion of Southeast Asia, a new phase of the then decade-long Pacific War (1931–1945). The Imperial government’s goal was a complete redrawing of the map of Asia. After centuries of European and American colonial annexations, Japan sought to create an “Asia for Asians.” The war planners called their project “The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” But was this a war of liberation, as they claimed, or a new form of imperialism?

It helps to frame a discussion of the origins of World War II in Asia as the product of unresolved colonial conflicts. Although using this frame will challenge many students’ understanding of the war (it creates a narrative that highlights Asian agency), doing so will help AP® World History: Modern students understand this history from a global perspective as they assess the continuities and changes in colonial territories for Topic 7.5. This approach can help students extend beyond their understandably American-centered view and add complexity and nuance to their understanding of the origins of World War II. At the same time, highlighting the contradiction between “Co-Prosperity” propaganda and the brutalities of colonial rule will show the dark ironies of Japanese imperialism.

History of imperial encirclement

In order to understand Japan’s desire to shake “off the yoke of Europe and America” through the creation of the “Co-Prosperity Sphere,” we must consider colonial expansion from a Japanese perspective. At the beginning of the twentieth century, after centuries of bearing witness to continued European invasion and annexation of Asian cities and nations, Japanese officials were understandably worried. Europeans weren’t the only powers to encroach upon Asia. The US began to project power into the Pacific, sending armed ships to Japan from 1846 to 1854 and pressuring the government to open its closed ports.

Japanese officials also learned from China’s “Century of Humiliations”: China’s defeat in the Opium Wars (1839–1842 and 1856–1860) and subsequent “unequal treaties” that gave European nations a powerful position in Asia. Appalled by Western behavior in China and the US attack on Korea in 1871 and annexation of Guam, the Philippines, and Hawaii in 1898, Japanese strategists felt increasingly encircled and vowed that their nation would not fall victim to a similar fate.

Japan as hero of Asia

By the turn of the twentieth century, only Siam (present-day Thailand) and Japan retained their independence in East and Southeast Asia. The Siamese kingdom survived by ceding territory and granting concessions to European powers, modernizing their diplomatic corps, and promoting Western education for the elite. Japanese modernization was even more aggressive, leading to fundamental political, economic, and cultural transformations.

This was a policy of defensive modernization, which supporters of newly installed Emperor Meiji (1868–1912) pursued. They pointed to once-powerful China, now embarrassed by its military failures and internal struggles. They argued that in order to protect Japan from American and European imperial aggression, Japan had to model itself on the West.

To do this, Japanese officials visited Europe and the United States to study the West. They were impressed with English factories and American railways, but also with Prussian administration and French academics. Based on their observations, officials imagined—and created—a new Japan. The government invested massively in the industrial sector, fanning the flames of a new nationalist spirit.

On its surface, rapid industrialization was a great success. However, the dramatic growth led to unintended consequences: profound social conflicts, labor militancy, and changing gender norms. Here, as in Europe, the government used nationalism to channel frustrations outwards and to deflect from and paper over domestic divisions.

“There Stands No Enemy Where We Go: Surrender of Pyongyang” by Toshihide Migita from a series on the Sino-Japanese War, 1894. © Pierce Archive LLC/Buyenlarge via Getty Images.

Japan didn’t just follow the Western example in industry; it also pursued a policy of colonial expansion. First, the newly industrialized Japan attacked China and seized Taiwan in the first Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895). A decade later, Japan shocked the world by destroying the Russian navy in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905). While both were wars of imperial aggression, the dramatic victories inspired many Asians. Here was an example of an Asian country learning from—and then defeating—the West.

Manchukuo Ministry of Overseas Affairs poster celebrating abundant harvests for Japanese in occupied Manchuria, 1927. © Pictures from History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Manchukuo Ministry of Overseas Affairs poster celebrating abundant harvests for Japanese in occupied Manchuria, 1927. © Pictures from History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Colonial expansion addressed a number of crises for Japan. Successful military expansion fueled nationalistic unity while new colonies provided raw materials, lumber, and food for the home islands. Japanese industry sold its products in protected markets abroad, and poor Japanese settled in newly acquired territories in mainland Asia.

Ironic imperialism?

This was just the beginning of Japanese imperialism. Japan became increasingly aggressive as it sought to extend its influence during the twentieth century. In 1910, after years of intimidation, Japan annexed Korea. When World War I broke out four years later, Japan quickly declared war on Germany, and within weeks seized the German-occupied Shandong Peninsula in China. With Europe distracted by the war, Japan issued its infamous “21 Demands on China” in January 1915. Then, from Korea and Shandong, Japan spread its influence over Manchuria. After the war, the Treaty of Versailles continued Japan’s control over Shandong as well as a number of formerly German islands in the Pacific.

Children depicted as warriors marching across Imperial Japan including Korea, Manchukuo China, and part of the Soviet Far East, c. 1940. © Pictures from History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Children depicted as warriors marching across Imperial Japan including Korea, Manchukuo China, and part of the Soviet Far East, c. 1940. © Pictures from History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

In 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria and established the puppet state of Manchukuo. Japan continued to increase its pressure on China, formally invading in 1937. However, years of fighting both the Chinese formal army and the guerillas of the Chinese Communist Party sapped Japanese strength. By 1941, war planners feared they would lose, without more resources. Thus, they launched a plan to occupy the oil fields, rubber plantations, rice fields, and mines of Southeast Asia. But these territories were held by European colonizers and protected by the shadow of the American Pacific Fleet. For Japanese planners, therefore, the attack on Pearl Harbor was a strategic move meant to give the Japanese Imperial Army and Navy a free hand.

While the hyper-nationalists and militarists who ran the Japanese Empire’s expansion were engaged in wars of outright colonial aggression, their propaganda promoted an image of liberators, not conquerors. “The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” did end Western domination of East and Southeast Asia, but it began a new form of colonialism.

After the initial euphoria of seeing their European colonial masters overthrown, nationalists from Vietnam to Java began to resent the increasing burdens of Japanese occupation. Pointing to forced labor, economic deprivations, and the brutal behavior of rank-and-file troops, many Southeast Asians remember Japanese rule as worse than the decades of Western occupation.

In a very different context, the Black feminist author Audre Lorde argued that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.” Adopting Western tactics to fight off colonialism, Japan soon became an aggressive imperialist power itself. Thus, there was a dark irony to Japanese imperialism’s claims of “Co-Prosperity.”

About the author: Michael G. Vann is a professor of history at California State University, Sacramento, where he teaches world history and courses on Southeast Asia, imperialism, and genocide. Vann is the author of The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt: Empire, Disease, and Modernity in French Colonial Vietnam (Oxford University Press, 2018).

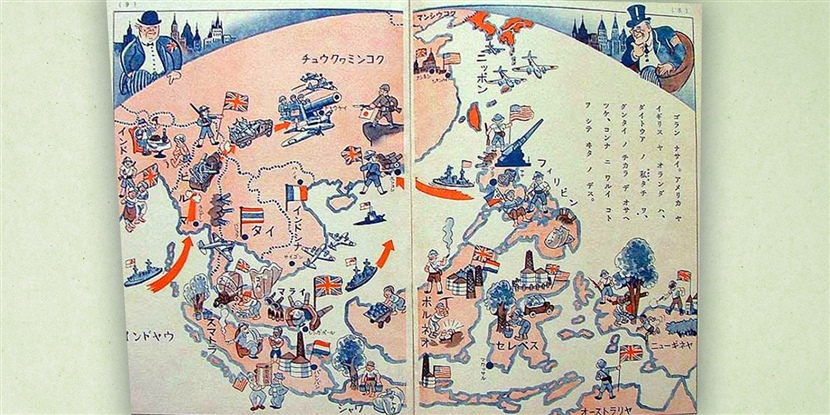

Cover image: Imperial Japan's proposed 'Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere', from the Daitoa Kyodo Sengen ('Manifesto for Greater East Asian Cooperation'), a propaganda booklet for children, c. 1940 (pre-Japanese involvement). Pictures from History / Universal Images / Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,