By Bridgette Byrd O’Connor

Louisiana, USA

The entire world breathed a collective sigh of relief when 2020 came to an end, but little did we know what would greet us at the start of 2021. Our students are living through a tumultuous time, and they are continuously bombarded with information from a variety of sources that can be contradictory and thus confusing. In addition, they’re exposed to an alarming amount of misinformation and disinformation. How do we help students make sense of it all so that they can make informed decisions about some very serious—and potentially life-changing—issues?

There are two historical reasoning skills that students need to distinguish fact from fiction and evaluate the motive and perspective of a source: claim testing and sourcing. These skills feature prominently in OER Project assets, but they’re also difficult skills to perfect. Even adults who consider themselves to be critical readers of information are often misled by sources that appear to be valid. These issues are amplified in our digital age when most people have access to social media, where a post can go viral in a matter of minutes. In the past two decades, fact-checking websites, social media platforms, and media organizations have attempted to combat both misinformation and disinformation. But these fact checkers only achieve their goals if people want to test the claims they read in the news or on social media.

I’m sure we’ve all experienced this problem in the classroom or at home. Yesterday, my daughter shared a rumor from the Capitol riot. I asked if she had fact checked what she was claiming to be true. In return, I got the obligatory eye roll and “ugh.” Translation: “Mom, you are so lame.” But I made her Google her “fact” to find a reputable source to check the claim she had repeated. Learning that her claim was wrong after checking for herself was more powerful than hearing that information from me—especially after the eye rolling. This is the uphill battle we’re all fighting as teachers, parents, and citizens. And that’s one reason why claim testing and sourcing skills are included as progressions in the OER Project courses. You’ll note that claim testing is found in both BHP and WHP, but sourcing is only in WHP. We consider claim testing to be a precursor to sourcing, so the idea is that as students build their claim testing chops in BHP, they’ll then be able to progress to the more challenging task of sourcing in WHP.

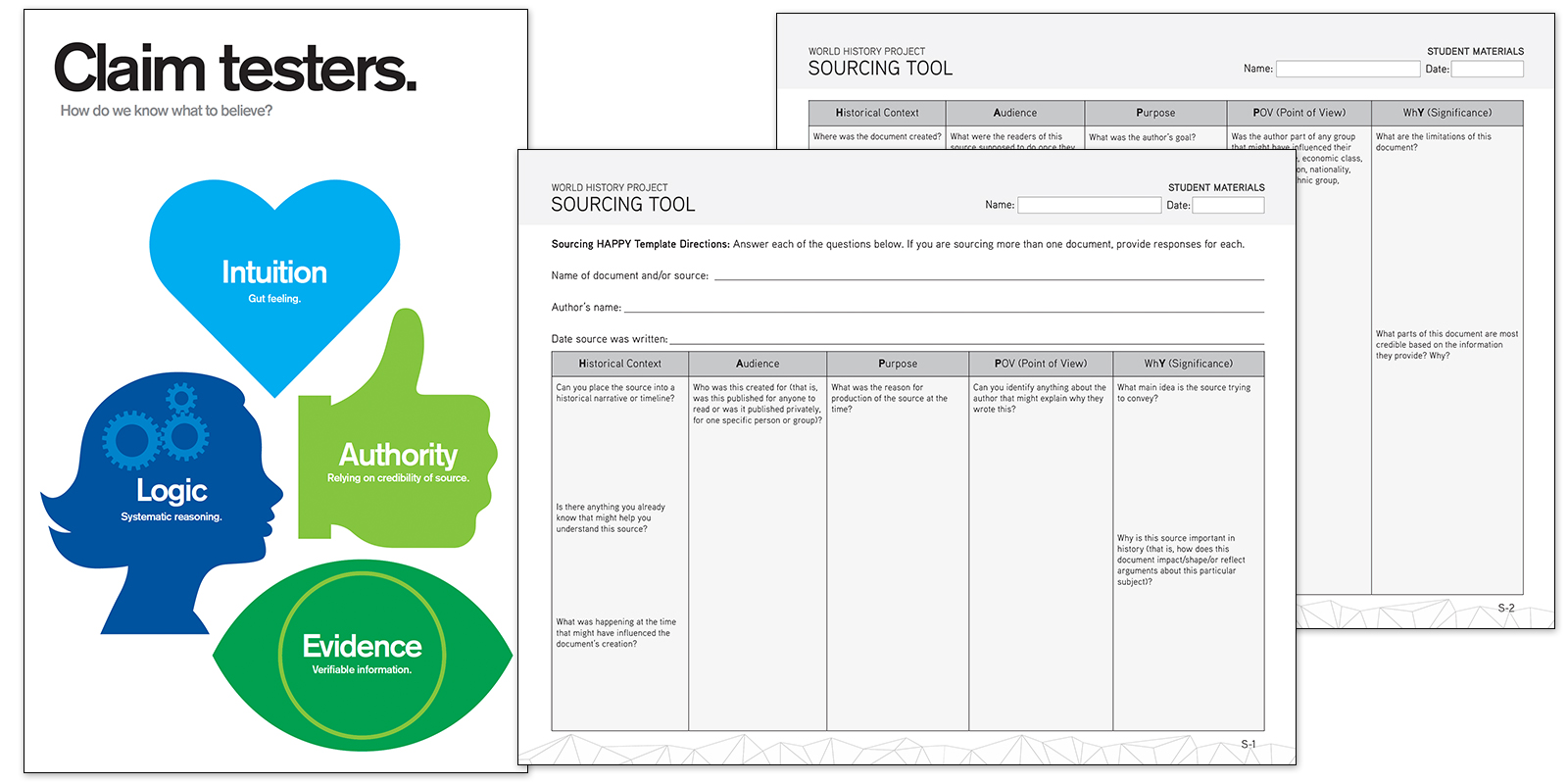

In both the World History Project and Big History Project courses, the claim-testing progression begins with an introduction to claim testing and terminology. In BHP, we first ask students to complete a Claim Testing Snap Judgment exercise by labeling a series of statements as true or false. Then, students categorize a collection of statements using the four claim testers—intuition, logic, authority, and evidence. In WHP, students begin with an introductory activity before moving on to examine the claim testers of authority and evidence in more detail. Later in the course, students will use their claim-testing skills to evaluate a selection of claims related to the content in a particular unit by finding supporting statements and counterclaims. They’ll also work on creating claims of their own in the Making Claims activities. These activities will help prepare students to evaluate historical claims and sources, but you can also use them as models to test claims that students encounter in their own lives.

|

New to claim testing? Check out this blog, which provides a comprehensive description of the claim testers, or this teacher-take on how to use claim testing in the classroom. To learn more about how to incorporate claim testing in the classroom, check out 8.2: Claim Testing in Teaching Big History, or 2.2: Claim Testing in Teaching World History. For guidance on the challenging, but oh-so crucial skill of sourcing, head on over to 4.4: Sourcing in Teaching World History-Origins (or 4.4 Sourcing in Teaching World History-1750). |

One of my favorite ways to do this for current events is to give students a news story that could be true, or a social media post from someone who is supposed to be an authority, and then have them use their claim testing and sourcing skills to evaluate it. For example, in 2012, John Fleming, then a Louisiana state representative, posted and linked to a story on his Facebook page. The story in question was from The Onion. We’re guessing you know this, but just for context: The Onion is a satirical news source. Although most students know this, it would be a great way to introduce claim testing and sourcing to your class. Have your students read the original article and complete the Sourcing Tool or ask them to evaluate the source using the four claim testers: intuition, logic, authority, and evidence. Had former Congressman Fleming used these skills to analyze the source and determine whether the author of The Onion piece was an authority, he would have saved himself a lot of bad press and embarrassment.

News organizations have entire pages devoted to fact checking these types of claims, and I’m sure there are countless examples of these types of stories floating around on social media. Or, like me, maybe your kids have discussed some questionable claims with you. I encourage you all to share some in the Community (but please remember to remove the names of any family or friends from the posts, unless, of course, they’re elected officials), along with ways those suspect claims might be used to help students sharpen their claim testing and sourcing abilities.

These types of exercises are usually fun and get students to apply claim testing and sourcing skills on articles and posts they see every day. But there are more troubling posts circulating on social media, such as those that have manipulated media or data that is skewed to produce desired results. And then there are the conspiracy theories, which have moved into the mainstream in frightening ways. It almost makes me nostalgic for the days when flat Earth and fake moon landings were the most bonkers conspiracy theories out there. Teaching students claim testing and sourcing skills from a young age can help combat their susceptibility to these “theories,” but the problem remains of how to teach these skills to those who have already jumped down the rabbit hole.

Looking for more? Join us in the OER Project Community today! And if you aren’t registered with us yet, create an account here for free access to the OER Project Community and more.

About the author: Bridgette Byrd O’Connor holds a DPhil in history from the University of Oxford and has taught the Big History Project and World History Project courses and AP US government and politics for the past 10 years at the high school level. She currently writes articles and activities for WHP and BHP. In addition, she has been a freelance writer and editor for the Crash Course World History and US History curricula.

Cover image: Composite image; teen girl using mobile phone while in the backseat of car, Chicago, USA. © Heather Wilson / 500px / Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,