By Natalie Martinez

Join Natalie Martinez at Fundamentals: The OER Project Conference for Social Studies on March 23! There's still time to register for the free webinar and see her keynote!

Imagine you’re looking at someone through a two-sided mirror. How does your perspective differ from theirs? How do your respective views differ when you’re looking at opposite sides of the same thing?

As an Indigenous scholar working in public education, this is a common experience I have when reading world-history textbooks. Those textbooks often seem like they were only interested in one side of the glass. This article will look at whose histories are reflected in our textbooks and whose knowledge gets left out of the historical narrative.

One unique place that can give us a glimpse into how history’s narratives impact real people is the First Americans Museum (FAM) in Oklahoma City. Visitors to the FAM are asked to consider how truths are told and how those narratives have become part of what counts as history. They experience ancient and contemporary stories about the 39 diverse Indigenous Nations of Oklahoma. As visitors leave, they’re reminded that there is more than one truth in history, but that what ultimately counts as knowledge is written by those from the dominant perspective. By doing this, the FAM reclaims the histories of Indigenous peoples who encountered one another and the institutions established by Euro-American society. This results in a more complete picture of many histories from the perspectives of Indigenous peoples.

The author at the First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City. The symbolism involved in these architectural designs is meaningful to the Nations represented in the museum. There are informational plaques that detail the significance of the stones, the arch, the hand, and the shape of the design. Courtesy of Natalie Martinez.

The author at the First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City. The symbolism involved in these architectural designs is meaningful to the Nations represented in the museum. There are informational plaques that detail the significance of the stones, the arch, the hand, and the shape of the design. Courtesy of Natalie Martinez.

Nearly 200 years after “Indian Territory” was established by the US government on what it believed to be barren land, the Nations of Oklahoma are thriving in a contemporary world and have adapted to the circumstances their ancestors endured during the 1830s Indian Removal Era.

Another place to begin to understand Indigenous histories is New Mexico, home to some of the most ancient civilizations. Ancient civilizations are the focus of sixth-grade social studies in New Mexico, but often the criteria for what counts as a civilization are biased toward Western measures of knowledge such as formal writing. This is why textbooks focus on classical civilizations as the ideal. Indigenous civilizations are thus demoted to “cultures” or “tribes,” which ignores their important historical impacts on world history. Rich oral histories and education systems of Indigenous peoples are reduced to myths or folklore. Ignoring Indigenous historical perspectives can have devastating effects in the present.

Our language can reinforce biases, and the word civilization is not the only example. Another example is the notion of the so-called New World. Who is seeing the Americas as new? The complex societies existing across the world prior to the fifteenth-century European voyages didn’t see themselves as new. The idea of a “New World” suggests that the Americas were vacant or uninhabited lands, which justifies the taking of lands and resources. This sort of language reinforces narratives that depict original inhabitants as combative—or, even worse, as complicit in losing their lands.

How can we address these biases and one-sided histories in our world-history classrooms? We must develop a curriculum to challenge the belief that colonization is positive and inevitable. Doing so turns the gaze of the two-way mirror to the other side of the glass. It interrogates the dominant narrative by basing the curriculum on counter-narratives. This has the power to reclaim the agency of oppressed peoples. We find an excellent case study in New Mexico schools. In 2020, when icons of oppression were being dismantled across the nation, curriculum designers in New Mexico responded with lessons that focused on the counter-narrative in the clash of the New World with the world already in existence for Pueblo peoples. This history revealed the brutality of Spain’s Juan de Oñate against the Pueblo peoples, specifically Acoma Pueblo, and the resurgence of Pueblo defenders, which lead to the Pueblo Revolution of 1680. When students are presented with Indigenous perspectives, their truth expands, and they can then understand the why behind contemporary conflict in their world. It is empowering for Indigenous learners to know that their histories matter too.

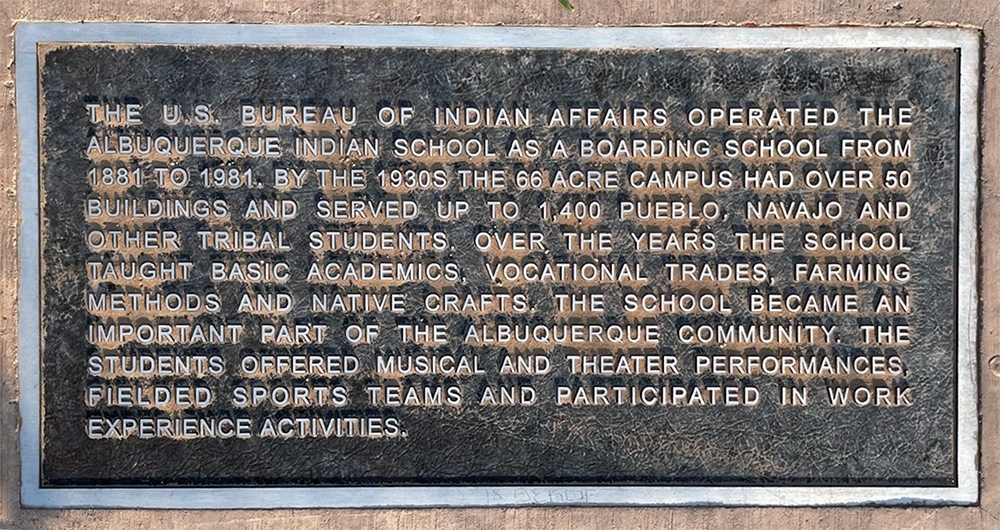

A plaque to commemorate the Albuquerque Indian School. Across the street from these plaques is an unmarked burial ground for children who never returned home from the school. Courtesy of Natalie Martinez.

A plaque to commemorate the Albuquerque Indian School. Across the street from these plaques is an unmarked burial ground for children who never returned home from the school. Courtesy of Natalie Martinez.

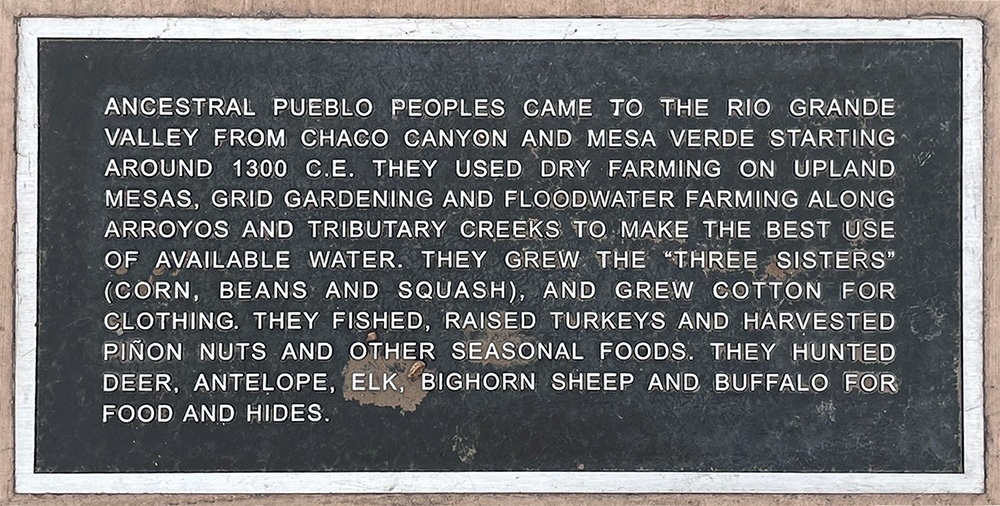

A plaque to acknowledge the background of Pueblo peoples in the region. Courtesy of Natalie Martinez.

A plaque to acknowledge the background of Pueblo peoples in the region. Courtesy of Natalie Martinez.

Such curricular practices counterbalance the dehumanization of people that allows lopsided history to portray “others” as inferior, and to make their histories and their existence inconsequential. The use of the “New World” writes people out of history so that it seems as if there are no obstacles to claiming land, resources, and Indigenous knowledge. The narrow criteria for “civilization” diminish the value of Indigenous life, culture, and history. History then becomes a tool of conquest and a method to support cultural theft and land grabs—because it participates in erasure.

Erasure is harmful because it takes lived experience and knowledge from the more than 500 Indigenous nations at the time of European contact and wipes them from the pages of history, or brands them as uncivilized. It affects contemporary Indigenous peoples on many levels. From the earliest times in the history of schooling in the United States, the attempted stripping of all “Indianness” from Indigenous children in order to make them seem more European has inflicted generational trauma on families, trauma that many are still dealing with. It has erased the original philosophers, scientists, engineers, scholars, and expert craftspeople from our collective memories, and it has made room for the continued violence toward Indigenous peoples in the forms of laws and practices aimed at suppressing their rights. For Indigenous youth in schools today, the battle of representation and recognition continues to be a daily challenge.

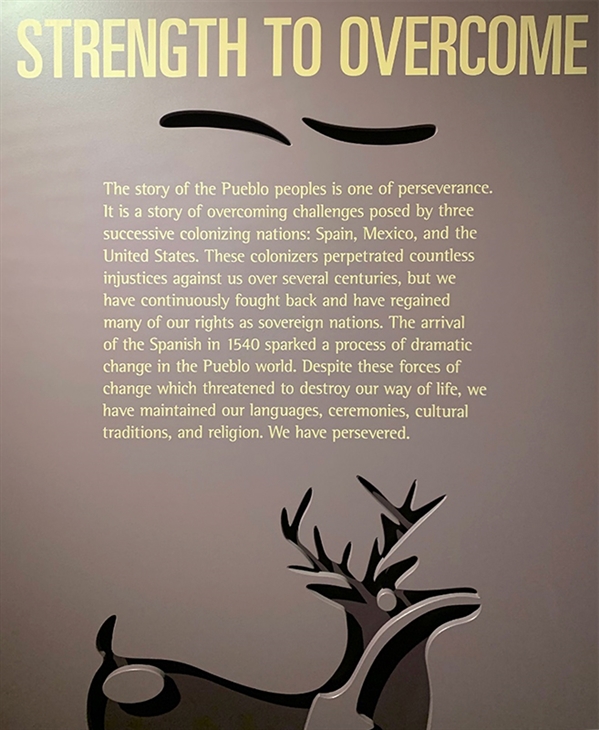

Indian Pueblo Cultural Center Museum placard claims the narrative of Pueblo history and resilience. Courtesy of Natalie Martinez.

Indian Pueblo Cultural Center Museum placard claims the narrative of Pueblo history and resilience. Courtesy of Natalie Martinez.

Efforts to address the reclamation of knowledge and to express Indigenous sovereignty continue today. Initiatives that address inequities of Indigenous representation in all fields of study and careers; acknowledge Indigenous languages and cultures; and recognize Indigenous rights across the world, such as with the International Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, are here, now. Educators have opportunities to help their students uncover missing narratives. We can reintroduce to learners the complex democratic governing systems of the Iroquois Confederacy; the sophisticated engineering designs of the Maya, the Inca and the Mexica; the complex international trade systems of ancient Pueblo peoples; or the canal systems of the Hohokam that provide the foundation for modern-day Phoenix; the expert seamanship and whaling enterprises of the Wampanoag; and the advanced agricultural practices of many Indigenous Nations across North America and South America. We can go beyond merely acknowledging the contributions of these peoples within histories of colonial domination. By delving into their diverse perspectives, we can begin to fully portray the complex societies and networks already in operation and extending across continents, long before European contact.

Indian Pueblo Cultural Center Plaza in Albuquerque, New Mexico. This is a business enterprise owned and operated by the 19 Pueblos in New Mexico and Sister Pueblo in Texas. The Center itself is built upon lands that were occupied by the former Albuquerque Indian School, a US government boarding school. Courtesy of Natalie Martinez.

Indian Pueblo Cultural Center Plaza in Albuquerque, New Mexico. This is a business enterprise owned and operated by the 19 Pueblos in New Mexico and Sister Pueblo in Texas. The Center itself is built upon lands that were occupied by the former Albuquerque Indian School, a US government boarding school. Courtesy of Natalie Martinez.

Indigenous activists continue to promote legislative policy efforts to address systemic issues with schooling. They advocate for access to quality education for Indigenous students and to expand education about Indigenous issues and histories in schools. These efforts are here, now. The Yazzie-Martinez court case transformed the focus of education in New Mexico by mandating equity in education for Native students. In other states, laws for equity in Native education such as Montana’s “Indian Education for All,” Washington’s “Since Time Immemorial,” and Oregon’s “Tribal History/Shared History” have begun to expand the idea of what counts as knowledge.

In schools and in teacher preparation programs, we can address the remnants of erasure and misrepresentation by deepening our understanding of Indigenous knowledge and interrogating our biases about Indigenous peoples. We all have a contribution to make to our world, and it could start simply with understanding more and knowing that we can begin prior to the point we’ve been led to believe is the beginning of history. We can start the story in other places, at other times. The big takeaway here is to acknowledge that there is no ONE history or ONE source of knowledge. There are different, often conflicting historical narratives and different funds of knowledge that different communities use to better understand their world.

Classroom resources:

- Teaching students to be critical consumers of history is important; teachers can actively engage students to think like historians and to question the information they are receiving. Using the National Council for the Social Studies standards and C3 Framework can help build dialogue. https://www.socialstudies.org/standards

- The Native Land app, found at https://native-land.ca/ has an interactive map with information about ancestral Indigenous lands, as well as lesson plans.

- An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States for Young People by R. Dunbar-Ortiz, adapted by D. Reese & J. Mendoza (2019) is a straightforward history that includes Indigenous perspectives. The accompanying lesson plans and curriculum guide can be found at the Beacon Publishing website: http://beacon.org/Assets/PDFs/IndigenousHistoryYAtg.pdf

- The Smithsonian National Museum of the Native American hosts virtual events and a teacher website called Native Knowledge 360° https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360

Further reading:

- An Indigenous Peoples History of the United States for Young People, Curriculum Guide http://beacon.org/Assets/PDFs/IndigenousHistoryYAtg.pdf

- First Americans Museum https://famok.org/

- Indigenous Wisdom Curriculum Project https://indianpueblo.org/indigenous-wisdom-curriculum-project/

- National Museum of the American Indian, Native Knowledge 360° https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360

About the author: Natalie Martinez, PhD (K’awaika-meh, Laguna Pueblo), is a professional educator. She was a principal and teacher at her Pueblo Nation, and taught at other schools in New Mexico. Dr. Martinez’s collaborations on Indigenous-centered curriculum projects include: Indigenous Wisdom; Indigenous New Mexico; and the curriculum guide for An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States for Young People. Her chapters appear in Luminous Literacies and The Yazzie Case: Interrogating the Yazzie/Martinez Lawsuit. Dr. Martinez most recently completed a visiting lecturer appointment at the University of New Mexico. Her research focus is education for Indigenous youth, professional curriculum development, and education policy.

Cover illustration: Composite image - View of Albuquerque Indian School, students and faculty, 1885. © PhotoQuest/Getty Images. Kyle Toya of The Southern Slam Dancers from Zia Pueblo performs the Eagle Dance at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque, NM on November 23, 2019. © The Washington Post / Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments