By Trevor R. Getz

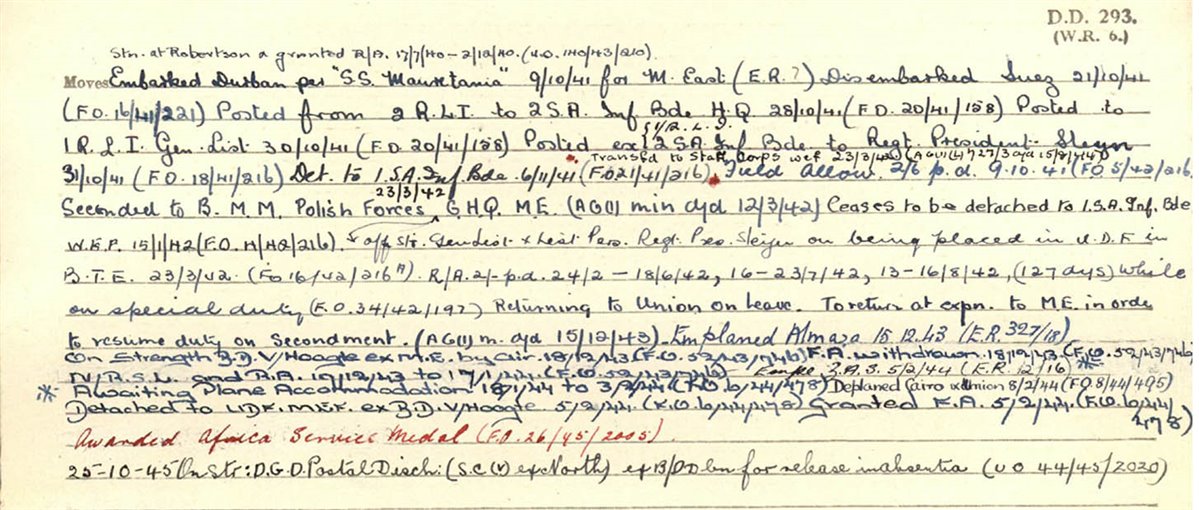

I became a historian because of the stories my grandfather told me of “the war.” Sitting beside him at the dining-room table as he sketched campaign maps and showed me photographs from his brief leave to marry my grandmother, I found a love for the stories of human struggle and passion that make up so much of history. Soon I was checking out the big picture books of World War II from my school library. Over time, I graduated to volumes full of descriptive text, and then analysis, and then went in search of original sources myself—in the process finding and studying my grandfather’s service record, a document that roots me in my research even today.

An excerpt from the author’s grandfather’s war records that includes leave home to get married. Courtesy of the author.

An excerpt from the author’s grandfather’s war records that includes leave home to get married. Courtesy of the author.

Many social studies and history teachers have similar stories of the moments of historical discovery that drew us into a love—and study—of the past. Many of them involve our families or visits to sites like Gettysburg or Ellis Island or our ancestral homes. But most of us had to make these discoveries on our own. Our teachers never invited those stories into the classroom or connected them to the textbooks and exams required to pass a course. Our students, too, have those connections to the past—family members, traditions, rituals, and sites of memory. Can we help make our courses more relevant and meaningful by inviting these stories about the past into the classroom?

The problem, of course, is that family and community recollections about the past don't play by the rules of history. Like the Origin Stories in the Big History Project, they are ways of explaining where we came from and how we became what we are rather than attempts to put facts in a logical order. Historians constantly bring narratives about the past into question, seeking to verify them as the most likely explanations for what happened and why. By contrast, we don’t set out to interrogate our grandparents when they relate their pasts to us. We value them as memories of what it means to be “us.” So how can we connect these different ways of talking about the past?

In 1992, researchers Luis C. Moll, Cathy Amanti, Deborah Neff, and Norma Gonzalez set out to connect the two in a groundbreaking education article based on their study of classrooms and households on the United States-Mexico border. They used the term “funds of knowledge” to describe family ways of knowing and sought to describe some ways teachers could bring these into the classroom. The method they suggested involved having students take on the role of researchers. They would access the knowledge of their family members, whom they recognized as experts, while the teacher assumed the role of learner. In this way, the researchers argued, students could learn to meaningfully connect the classroom to their homes, families, and lives.

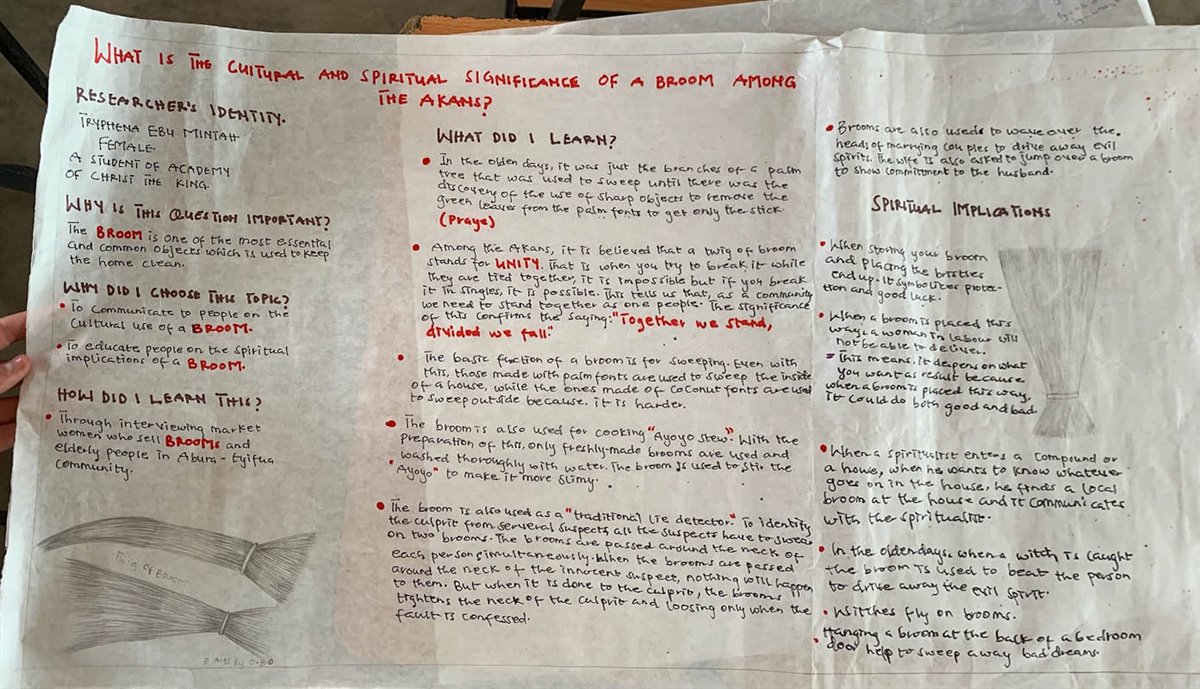

In the summer of 2022, a team of researchers including OER Project advisory board member Tony Yeboah and myself conducted a similar project in Ghana. Working with local teachers, we designed a two-week activity in which students defined their own research projects in their own communities, acquired oral history methods, then relied on their families and community members to generate evidence. Students studied spiritual sites, the lives of their teachers, and even the histories of everyday objects, such as brooms. They then invited their families to their presentations at school, where the conversation continued. In the end, we found that students’ motivation to study history had significantly increased.

A project poster from the summer 2022 community history course at Academy of Christ the King, Cape Coast, Ghana, focused on the significance of the broom among the Akan communities. Courtesy of the author.

A project poster from the summer 2022 community history course at Academy of Christ the King, Cape Coast, Ghana, focused on the significance of the broom among the Akan communities. Courtesy of the author.

How can you help your students bring their funds of knowledge into the classroom? Well, first of all, you should check out the original article by Moll, Amanti, Neff, and Gonzalez. You can also start by having students write or draw their own histories and recognize that much of what they know comes from their families and community as well as their own memories, all of which are valuable ways of knowing the past. For recent events, find ways to bring family knowledge together with the big events of the recent past, as I do in this article about World War II.

You might be a bit wary about this strategy because you anticipate that students’ funds of knowledge may contradict the sources in the classroom. You’re right—they might! But think about using these contrasts to open up a conversation about the different kinds of knowledge and how to understand them. In some cases, this journey matters more than having students reach a conclusion about who is “right” in the classroom setting.

If you want to try out this technique, just remember the ground rules for using household funds of knowledge: help students become researchers by sharing skills like oral history methods; recognize family members as experts in their shared past; and be open to assuming the role of learner. The big secret is that this can be quite a fun role reversal for you, the teacher!

About the author: Trevor Getz is professor of African history at San Francisco State University. He has written 11 books on African and world history, including Abina and the Important Men. He is also the author of A Primer for Teaching African History, which explores questions about how we should teach the history of Africa in high school and university classes.

Cover image: The author’s grandfather, Dan Gonski (front row, third from left), serving with the Second Polish Corps during World War II. Courtesy of the author.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments

-

Bram Hubbell

-

Cancel

-

Up

+2

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Comment-

Bram Hubbell

-

Cancel

-

Up

+2

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Children