Trevor Getz, OER Project Team

San Francisco, USA

What causes COVID-19?

Is 5G radio technology causing or exacerbating the epidemic of COVID-19 that is currently sweeping the globe?

Of course not.

We know 5G isn’t the cause because we can use the scientific method to establish a chain of evidence that connects a corona-shaped virus—SARS CoV-2—to the symptoms that we experience as COVID-19. The scientific basis for establishing these kinds of connections was first developed by German philosopher Robert Koch in the nineteenth century. He discovered that two diseases—cholera and tuberculosis—were caused by microorganisms, specifically bacteria. More importantly, Koch developed a set of rules to identify and isolate these disease-causing microorganisms. These rules, called Koch’s postulates, begin with Koch’s assertion that a specific microorganism must be found in all people and animals suffering from a particular disease. He then went through a series of steps to culture the microorganism, show that it caused the disease when inserted into a healthy person or animal, and then demonstrate that the microorganism hadn’t changed between the two hosts. Later, Koch’s postulates were updated to deal with viruses, but it turns out that the original postulates work pretty well for SARS-type viruses, and in this case demonstrate that the SARS CoV-2 virus causes the COVID-19 disease.[2]

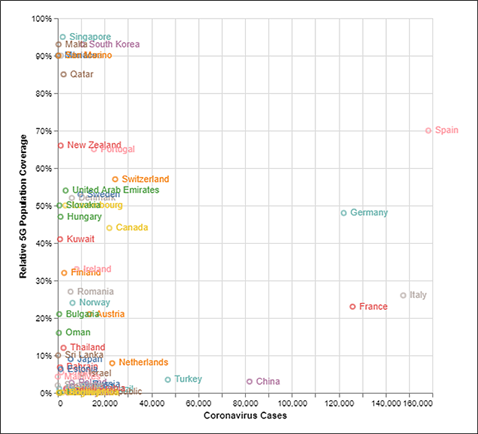

By contrast, the evidence of any connection between 5G and COVID-19 is not only lacking, but actually negative. That means that the evidence we have points to no link between the technology and the disease. For example, the chart below shows that some of the places with the highest rates of 5G coverage, such as Singapore and Malta, have had very few coronavirus cases, whereas some places with very low 5G coverage, such as China, have had large numbers of cases of COVID-19.

Graph to demonstrate that 5G is not correlated at all with the spread of coronavirus. Sources: 5G data and Coronavirus data.

Graph to demonstrate that 5G is not correlated at all with the spread of coronavirus. Sources: 5G data and Coronavirus data.

Yet despite this and other compelling evidence to the contrary, people around the world mistakenly believe that 5G Internet causes COVID-19. In Europe, people have even sabotaged 5G towers. And this misconception matters far beyond vandalism and property destruction. If we want people to behave in ways that limit COVID-19 infections, we have to convince them that it is important to wash hands and socially distance—behaviors that we know are helpful in combating the spread of viruses. At the same time, laughing at or ignoring people who have these kinds of ideas doesn’t help diminish the threat. Instead, by understanding where these ideas come from, we can slow the spread of misinformation, and support behaviors that can help save people’s lives!

The 5G “truthers” are by no means the first people to look for explanations of epidemics in strange places. For example, for years some people in the United States have believed that weak electromagnetic fields (like nearby power lines) cause cancer, although there is no evidence to support this argument.[1] There are dozens of other examples throughout history. Often, vulnerable communities are blamed. The Romans accused Christians of spreading smallpox, and fourteenth-century Europeans believed that Jews caused the bubonic plague by poisoning wells. These theories led to persecution of both of those groups. Other attempts to get to the cause of disease have had dire results for the entire society. In the 1850s, many Xhosa people in South Africa believed that a disease killing their cattle was a result of witchcraft. On the advice of a prophetess, they killed their remaining cattle and burned their crops to purify their society. The result was mass starvation and an inability to resist conquest by the British.

None of these historical groups, however, had access to Koch’s postulates and the kinds of evidence-based scientific research that we have. None of them really understood that these diseases were caused by naturally occurring organisms such as bacteria and viruses. However, those of us living in the twenty-first century do have that knowledge. We can use it to shape our behavior and policies in ways that actually reduce the spread of these organisms, if we choose to do so. Why do so many people embrace theories that lack hard evidence?

COVID-19 conspiracy theories

We can understand this problem partly by looking at these explanations as examples of what we often call conspiracy theories. Joanne Miller, associate professor in the departments of political science and psychology at the University of Delaware, studies why people believe conspiracy theories. These are usually theories about a negative event that assumes that nothing is as it seems, but rather was organized by evil conspirators acting for their own gain. Miller finds that people believe these kinds of theories for a variety of reasons. One of these is a need to restore control. People who believe these kinds of theories perceive that the world is uncertain and out of their control, and that they aren’t able to manage it.

Conspiracy theories also arise when people feel anxious and threatened. What a conspiracy theory does is cut through the uncertainty and anxiety and identify a clear, simple cause of the problem—something they can focus on and deal with. “However far-fetched the theory may be, tying up confusing events with a simple, neat conspiratorial bow fulfills the individual’s need for order and reduces [associated] anxiety”.[2] Moreover, people tend to believe conspiracy theories that generally support their overall political, identity, religious, or cultural beliefs.

Pandemics fit all of these descriptions. They threaten people’s beliefs and culture by forcing them to make radical changes in their behavior – like not going to church or not hanging out with their friends. The resulting inability to control their world causes great anxiety. People naturally seek an easy explanation for what’s causing the rapid and uncontrollable spread of deadly disease, and they come up with causes that support their existing worldview.

Three big conspiracy theories have emerged to explain the coronavirus virus, none of which is supported by any meaningful evidence. The first, as we already mentioned, is that it is caused by 5G technology. A second is that it was produced by the US government. The third is that it is a bioweapon engineered by the Chinese government to wage war on America.[3] Each of those explanations identifies a clear, easily understandable cause. And each appeals to a group of people based on their preexisting identities. People who generally think new technology is dangerous are predisposed to blame 5G. People unhappy with parts of US government are perfectly happy to accept the idea that they’re the cause. People who are strongly politically partisan and hold racialist ideas are likely to believe that coronavirus is a Chinese bioweapon.

Conspiracy theories can spread rapidly. Social media helps bogus theories get traction, usually without anyone checking the evidence.[4] But some theories are also supported by bad actors—such as governments looking to cover up their mistakes and blame their enemies, or scammers trying to make money.[5]

What can you do about it?

So what is your responsibility as an individual? First, whenever you encounter an explanation for coronavirus (or any other problem), consider carefully whether it is worth sharing or if it should guide your actions. Be particularly careful when you read ideas that are easy to agree with. Check whether there is evidence behind them. Try to figure out whether the idea is the product of a scientific test. Look for whether trusted and academic sources support this idea. Don’t share anything without doing this kind of analysis first. If you do figure out that some information is incorrect, especially if it is shared by a friend, tell them that you think it’s not accurate. But be polite rather than rude or patronizing. Also, take advantage of the fact that many social media platforms have ways to report disinformation. By following these guidelines, you can help slow the spread of misinformation and instead can support the spread of advice and practices that help us respond to this pandemic!

About the author: Trevor Getz is a professor of African and world history at San Francisco State University. He has been the author or editor of 11 books, including the award-winning graphic history Abina and the Important Men, and has coproduced several prize-winning documentaries. Trevor is also the author of A Primer for Teaching African History, which explores questions about how we should teach the history of Africa in high school and university classes.

Cover image: It ain’t the 5G, people! By OER and Peter Quatch, CC BY-NC 4.0. http://peterquach.com

References

[1] National Cancer Institute, https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/radiation/electromagnetic-fields-fact-sheet.

[2] Joanne M. Miller, Kyle L. Saunders, and Christina E. Farhart, “Conspiracy Endorsement as Motivated Reasoning: The Moderating Roles of Public Knowledge and Trust,” American Journal of Political Science, 60 (2017): 824-845; 825.

[3] There are other theories, such as the idea that coronavirus doesn’t really exist, but we won’t look at those ideas closely here.

[4] Facebook is beginning to inform people when they see or comment on debunked coronavirus theories. Shannon Bond, “Did You Fall for a Coronavirus Hoax?: Facebook Will Let You Know,” NPR, April 16, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/04/16/835579533/did-you-fall-for-a-coronavirus-hoax-facebook-will-let-you-know

[5] Max Fisher, “Why Coronavirus Conspiracy Theories Flourish. And Why It Matters,” The New York Times, April 8, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/08/world/europe/coronavirus-conspiracy-theories.html .

[1] Ron A.M. Fouchier, Thijs Kuiken, Martin Schutten, et al., “Koch’s Postulates Fulfilled for SARS Virus,” Nature, 423, 240 (2003), https://doi.org/10.1038/423240a.

[2] Linlin Bao, Wei Deng, Baoying Huang, et al., “The Pathogenicity of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in hACE2 Transgenic Mice,” bioRXiv, https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.07.939389.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,