By Rachel Phillips, OER Project Learning Scientist

Technology has helped ensure that our day-to-day lives are maximized for each of us as individuals. Your morning might start with an Alexa- or Siri-delivered weather report for your ZIP code, followed by a news update, tailored to your interests—so “yes” to last night’s game, “no” to the stock market. You can preorder your coffee so that you can swoop right in to pick it up, no standing in line. Your health app might remind you to stand and walk around the room every 30 minutes. These are just some of the ways technology allows us to maximize our time in very individualized ways. Who wouldn’t want a learning experience that provides that kind of individual guidance?

While advances in machine learning and natural language processes have improved this kind of educational technology, these technologies haven’t not reached maximum potential in terms of personalizing experiences for all students. There is a ton that technology can do, but there’s still a long road ahead, especially when it comes to social and emotional learning. Additionally, the increased use of technology has started to impact the actual structure and function of people’s brains. Attention spans are changing, memory is affected—these are impacts that have been repeatedly verified by both EEG and fMRI studies (Korte, 2020).

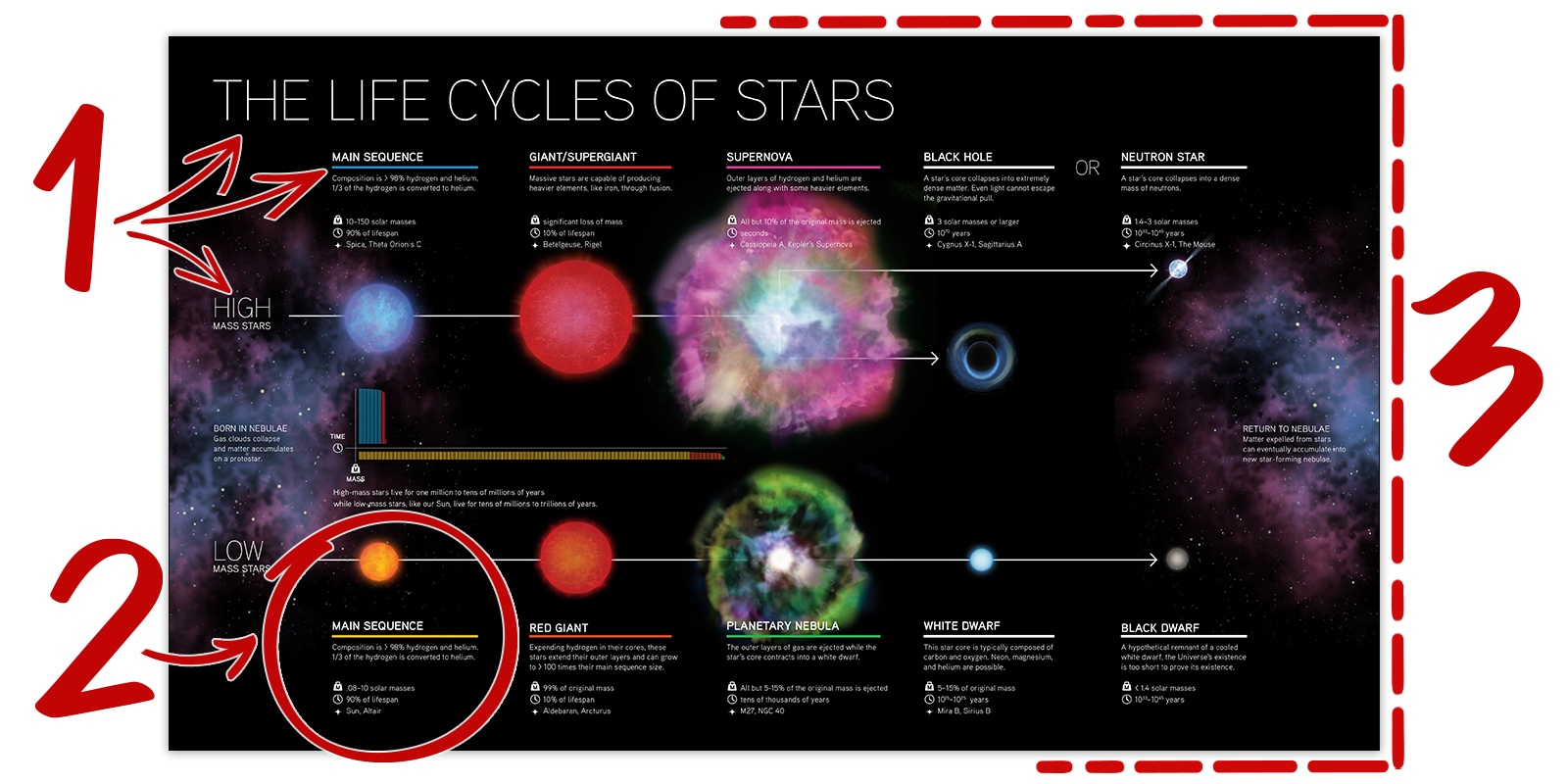

These technology-related changes add even more variability into our classrooms, and make teaching and supporting students in reading trickier than ever before. While the influence of technology has impacted all subject areas, social studies and ELA are particularly influenced by the fact that access to what we can and should be able to read has expanded exponentially. Reading has gone far beyond the standard textbook. Students are reading online, and they’re reading a diverse set of texts. Now, we’re not saying that’s bad—OER Project courses use a broad definition of what it means to “read.” Because of this, we regularly ask students to “read” videos, infographics, historical comics, primary and secondary sources, maps, and data. How do we support these changing brains in this broadly defined reading?

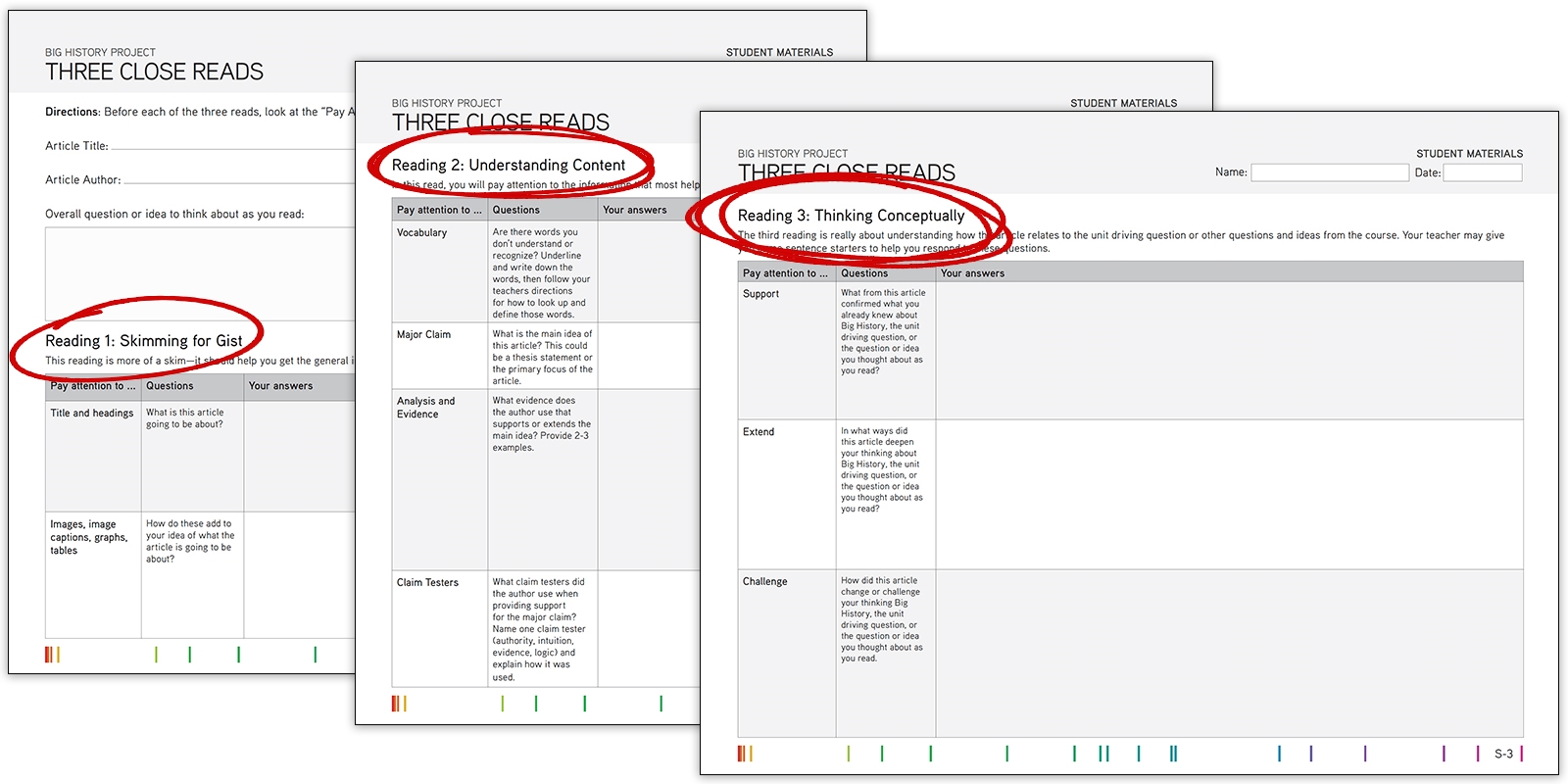

The first way to support students is by using OER Project’s Three Close Reads approach. The general idea of three close reads can be used when encountering anything that we “read.” There’s always a first (short) read, where you skim for gist or get the general idea of what something is before really diving in—just a bit of a primer. The second read is where you really dig into the weeds to understand the details, and the final read gives you time to think about how what you’ve read applies to what you already know and understand.

If your students are reading an infographic, for example, the first read might just be to look at the title and major headers, and to check the data sources for credibility. For the second read, students might answer specific questions that help orient them to the main features of the infographic. For the third ready, they might do more of a synthesis read to understand the bigger picture of what the infographic is trying to convey and why.

This approach personalizes learning for each student to some degree, especially the first and third reads. The first read helps students activate prior knowledge about the topic (or, if there isn’t prior knowledge to speak of, it starts to give them an idea of what’s to come, helping them to start building ideas). The third read is the most personalized—in OER Project courses, we always ask students to discuss how what they just read supports, extends, or challenges what they already knew. This is directly connected to the knowledge that the student came in with, or just gained during the first two reads, which makes it personally relevant. Personal relevance improves engagement, which in turn deepens learning. However, this is personal to content knowledge, and personalization can go even further than this.

The second way to support students is by having them personalize their own approach to reading. Learning is such a complicated process, and while we can give students all the tools in the world, they need to understand how they learn best to be successful. How can you help them do this? One way is by having them run some experiments on themselves early in the year so they can discover how (and maybe when) they do their best reading.

Choose a task that students will do repeatedly throughout the year, a task that you will assess. Reading articles independently is a great example. Then, have students engage in that tasks by altering their learning environment each time they read. Perhaps the first time they read, they do it on paper and in a quiet room. The next time might be on paper with music playing. Perhaps the third time is reading on-screen while taking notes on paper, and so on. Students should track the elements of their environment, changing one variable at a time, and seeing how the environment impacts the outcome. You and your students can likely come up with a lengthy (and fun) list of variables to test, but here are some examples: time of day, location, noise level in the room, paper, pencils, screens, keyboards, note taking and annotation strategies, or whether it was before or after a meal.

While technology often feels like a solution for differentiation, there are low-tech and no-tech ways we can facilitate individualized learning experiences in reading for our students. The use of Three Close Reads and learning environment experiments are great ways to tap into individual student needs. Have you found other ways to make reading feel individual to your students? We’d love to learn more about your strategies for doing this—share them in the OER Project Teacher Community!

About the author: Rachel Phillips, PhD, is a learning scientist who leads research and evaluation efforts for the OER Project, as well as develops curriculum for their courses. She is elementary certified, has taught in K–12 schools, and currently serves as an adjunct professor for graduate courses in American University’s School of Education. Rachel was formerly Director of Research and Evaluation at Code.org, faculty at the University of Washington, and program director for National Science Foundation-funded research. Her work focuses on the intersections of learning sciences and equity in formal educational spaces.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,