By Rachel Phillips, OER Project Learning Scientist

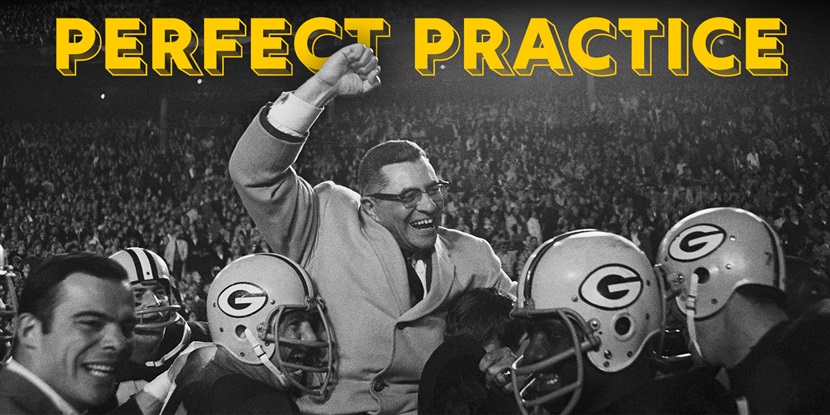

Vince Lombardi has been credited with saying, “Practice does not make perfect. Only perfect practice makes perfect.” This is hard to argue with, but it does beg the question, what does this look like in the classroom? How can we facilitate “perfect practice”? One of the best ways to do this is by using assessment for learning, rather than using assessment of learning. It’s a subtle turn of phrase, with a pretty massive difference in outcomes.

Before we get to the difference between assessment of and assessment for learning, let’s first think about practice and what is often referred to as the development of expertise. We’re trying to help our students become more expert at the work they do in school to prepare them for life. It can take thousands of hours to become a professional athlete, dancer, writer, or musician. One world renowned expertise expert (yes, that’s a thing!), K. Anders Ericsson, suggests that experts are made, not born. The development of expertise in anything takes loads and loads of time. The literature that looks at the development of expertise refers to routine experts and adaptive experts. Routine experts are those who are really good at doing the same thing over and over again. Adaptive experts, on the other hand, are those who can take their expertise and innovate on it, and in doing so advance their skills and their knowledge of the field. And I daresay, in today’s ever-changing world, we should be doing what we can to foster adaptive expertise in our classrooms.

So how do we do that? Teachers are already pressed for time, so where can we find “loads” of it? Turns out, assessment is the solution. The idea goes like this: If you can’t measure something, you can’t improve it. It’s really important that we measure all the learning that happens in the classroom, but it’s also important that we do this in the most effective ways possible. So what’s effective? It turns out, formative assessment is where it’s at. We’ll explain why in a second, but at this point you may be wondering, why not summative assessment? Think about the form summative assessment takes in the classroom (not to mention standardized tests). It’s the end of a unit and you give your students a unit test. They study a bunch (maybe the right stuff, maybe not, hard to say), and once it’s administered, you take home the test, spend a bunch of time grading and commenting on it, and hopefully return it to your students within a week. Upon returning those papers, what happens? Well, if your students are anything like me, they look at their grades...and do nothing else. This means you have made an assessment of their learning. The learning stops there.

Now if we pivot back to formative assessment, or as we like to say at OER Project, informative assessment, this is where we get into assessment for learning. As compared to summative assessment, formative assessment is done at a smaller scale, is easily repeated, and is faster and for lower stakes—all of which allows for development of expertise. It’s about more continual check-ins, rather than a one-shot check for understanding. So how can you and your students get into the practice of formative assessment? As a teacher, it’s important for students to be aware of the goals they’re trying to meet, and they need examples of what “good” looks like. They need to understand the ways in which their learning might progress. Skills progressions help foster this. Rubrics, accompanied by exemplars of student work, are also a great way to help students understand their goals. And those exemplars can’t just be perfect; students need to see a range of quality to know how they get from one level to the next.

Students also have to be made responsible for assessing their own learning. Learning how to assess themselves is a skill that will serve them throughout their lives. Fostering metacognitive practices (asking students to think about their own thinking) helps make students aware of what they know, what they don’t know, and what they need to do to improve. This will support them both in and out of the classroom, and will help them to be more adaptive when they encounter new information, need to solve new kinds of problems, or discover they aren’t learning or improving in the ways they had hoped or intended. What are some ways that you use assessment for learning in your classroom? Share your ideas and formative assessments to help students achieve perfect practice in the OER Project Online Teacher Community.

About the author: Rachel Phillips, PhD, is a learning scientist who leads research and evaluation efforts for the OER Project, as well as develops curriculum for their courses. She is elementary certified, has taught in K–12 schools, and currently serves as an adjunct professor for graduate courses in American University's School of Education. Rachel was formerly Director of Research and Evaluation at Code.org, faculty at the University of Washington, and program director for National Science Foundation-funded research. Her work focuses on the intersections of learning sciences and equity in formal educational spaces.

Cover image: Vince Lombardi being carried by Green Bay Packers players after defeating the Dallas Cowboys. ©Bettmann / Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments

-

Andrew Jones

-

Cancel

-

Up

+2

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Comment-

Andrew Jones

-

Cancel

-

Up

+2

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Children