By Bridgette Byrd O’Connor

When students are working at the large scales of Big History and world history, they can easily come to the conclusion that human history is a story of constant progress. But progress is not a straight line. There are often bumps in the road—obstacles along the path to progress. And yet, in many cases, these challenges have been overcome, and in the process have contributed to the long arc of our collective learning. We can see one pungent example of this in the stinky waters of nineteenth-century London.

As humanity entered the industrial age, change accelerated. Much of that change was good stuff—increased productivity and new inventions. On the other hand, uncontrolled inequality; poor labor conditions; gender, racial, and class discrimination; and industrial imperialism all represented negative outcomes of industrial growth. For residents of London, however, it was the “Great Stinks” of the River Thames and the uncontrolled spread of diseases such as cholera that drew the most attention. How did these obstacles of industrial progress help us change and grow over time—and what happens when humans fail to learn from these challenges?

The stench smelled round the world

As more people crammed into industrial cities like London and Liverpool, they produced smog, grime, germs, and excrement. Diseases such as cholera and “fragrant” odors in cities around the world weren’t new, but in the nineteenth century they reached unprecedented degrees of disgustingness.

In the early nineteenth century, deaths from cholera soared as imperial militaries, increased trade, and faster transportation spread the disease around the world. From 1817—the start of the first cholera pandemic in India—to the end of the nineteenth century, global deaths from cholera climbed into the tens of millions. During the first outbreak, India’s death rate skyrocketed. As the disease traveled, most likely on board British imperial ships departing India, new pandemic waves hit Indonesia, China, Russia, Poland, the Americas, France, and the United Kingdom.[1]

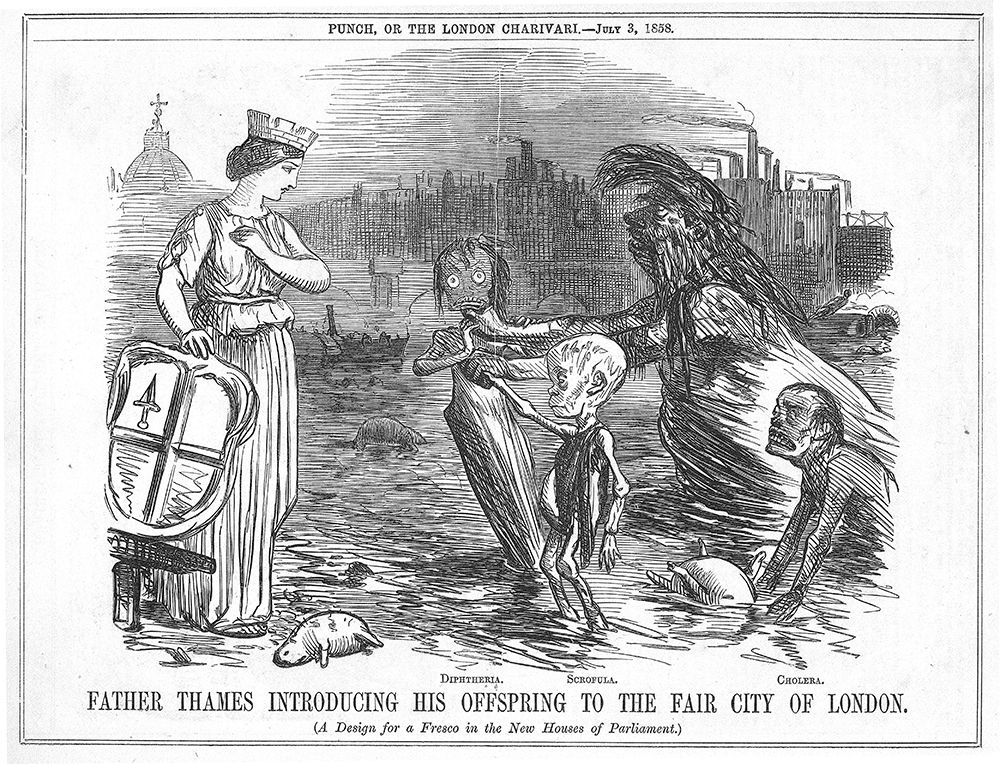

When the second cholera pandemic arrived in Europe in 1831, the disease flourished in urban industrial regions. London, then the most populous city in the world, also had some of the world’s most polluted rivers. London’s large population and large factories certainly contributed to the pollution; however, so did the 150,000 households that enjoyed piped water from the Thames and Lea Rivers. Industrial capitalists and aristocrats took advantage of these innovations and installed running water and flush toilets in their homes, bathing and flushing to their hearts’ content. They also convinced lawmakers to lift an 1815 ban that prevented the connection of household drains to the city’s sewers. Regrettably, London’s sewers hadn’t quite gotten Parliament’s progress memo: raw sewage now flushed directly into the rivers. Of course, having the Thames as your sewer poses a problem when it’s also your main source of drinking water. Soon all those new pipes supplying “fresh” water to households and street pumps became faucets of disease and death.

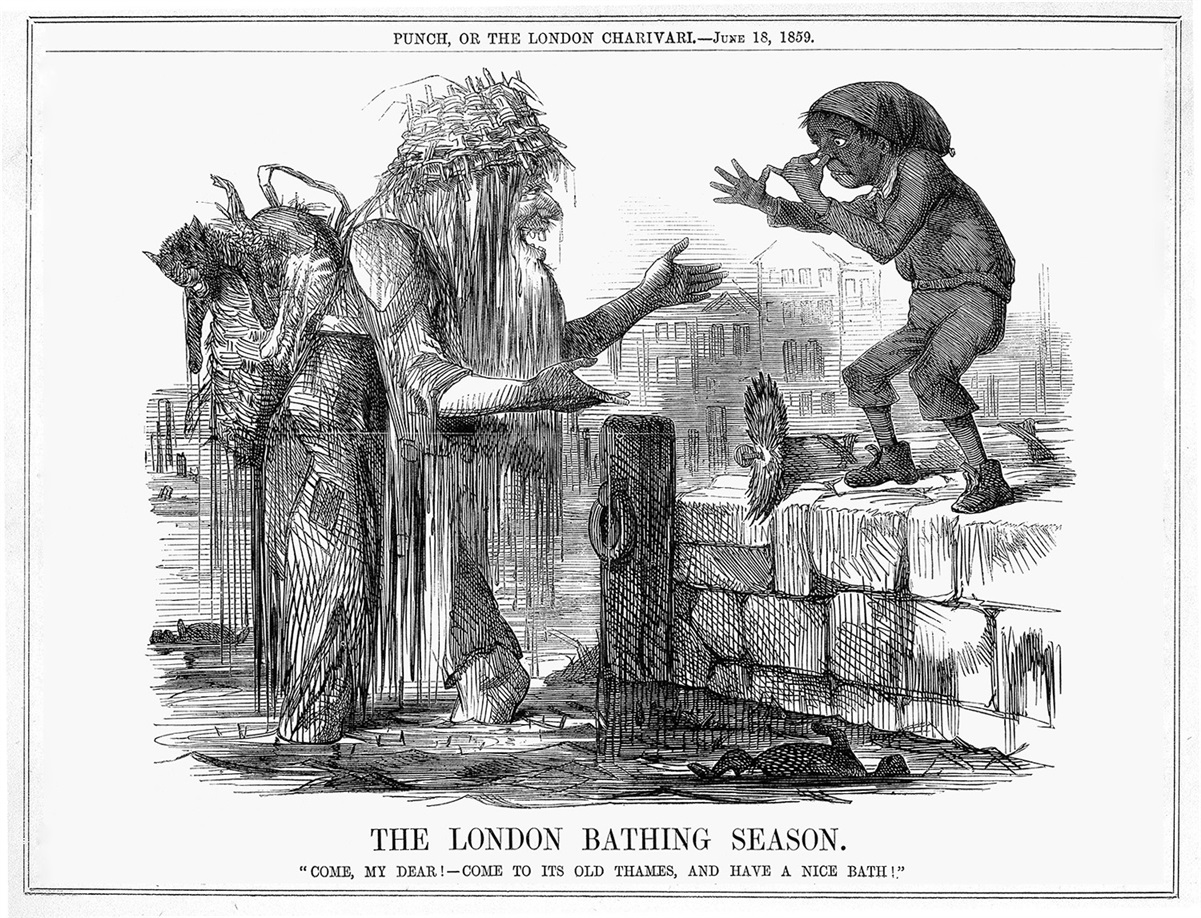

“The London Bathing Season: Come, my dear!—Come to its Old Thames, and Have a Nice Bath!” Punch Magazine, June 18, 1859. © The Cartoon Collector / Print Collector / Getty Images.

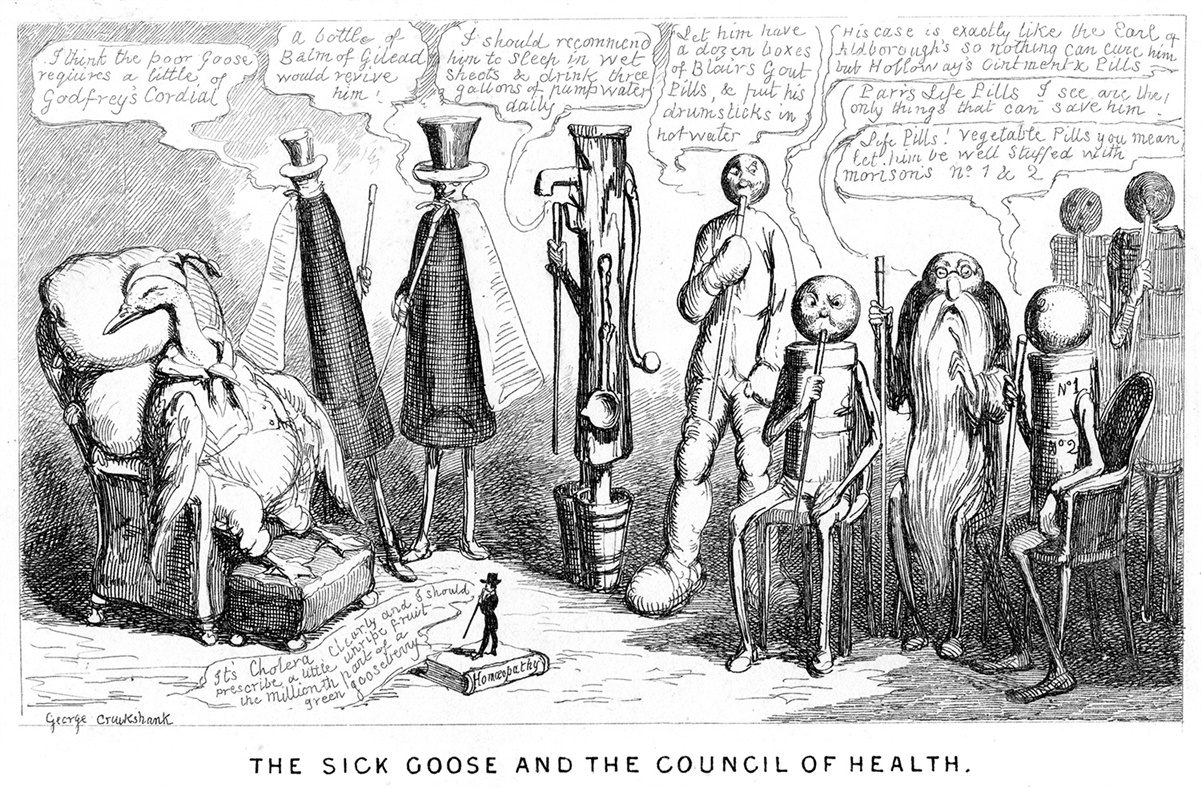

Unfortunately, most scientists at the time believed cholera was caused by noxious air—miasma—rather than contaminated water. Considering miasma theory’s long history and its general acceptance among European scholars,[2] it’s not surprising that most people blamed foul air for the disease. But as long as excrement continued to infect the water supply, cholera continued to return to the city. The results were the pandemics of 1848–1849 and 1853–1854, which killed over 25,000 Londoners. Then, in the summers of 1858 and 1859, the state of the Thames became unbearable. The heat essentially simmered the raw sewage, releasing such a foul odor that Members of Parliament were driven from their newly constructed offices along the river.[3] This wasn’t the first time the stench of the Thames became problematic; it was merely the worst of the Great Stinks. Of course, putrid smells from sewage-contaminated rivers weren’t confined to London—Great Stinks and cholera pandemics occurred in other major cities including Calcutta, Moscow, New Orleans, Tokyo, Paris, and New York.

“Father Thames Introducing His Offspring to the Fair City of London,” Punch Magazine, 1858. Father Thames’ offspring included diseases like cholera. © Universal History Archive / Getty Images.

“Father Thames Introducing His Offspring to the Fair City of London,” Punch Magazine, 1858. Father Thames’ offspring included diseases like cholera. © Universal History Archive / Getty Images.

Breakthroughs and reform

The “Great Sanitary Awakening” that occurred in response to cholera epidemics and the Great Stinks was not the first reform movement of the long nineteenth century. But the sanitation movement was unique in its creation of interdisciplinary global efforts to investigate the causes of communicable diseases and improve sanitation and hygiene. The fight to eradicate these hindrances to industrial progress eventually led to the development of germ theory.

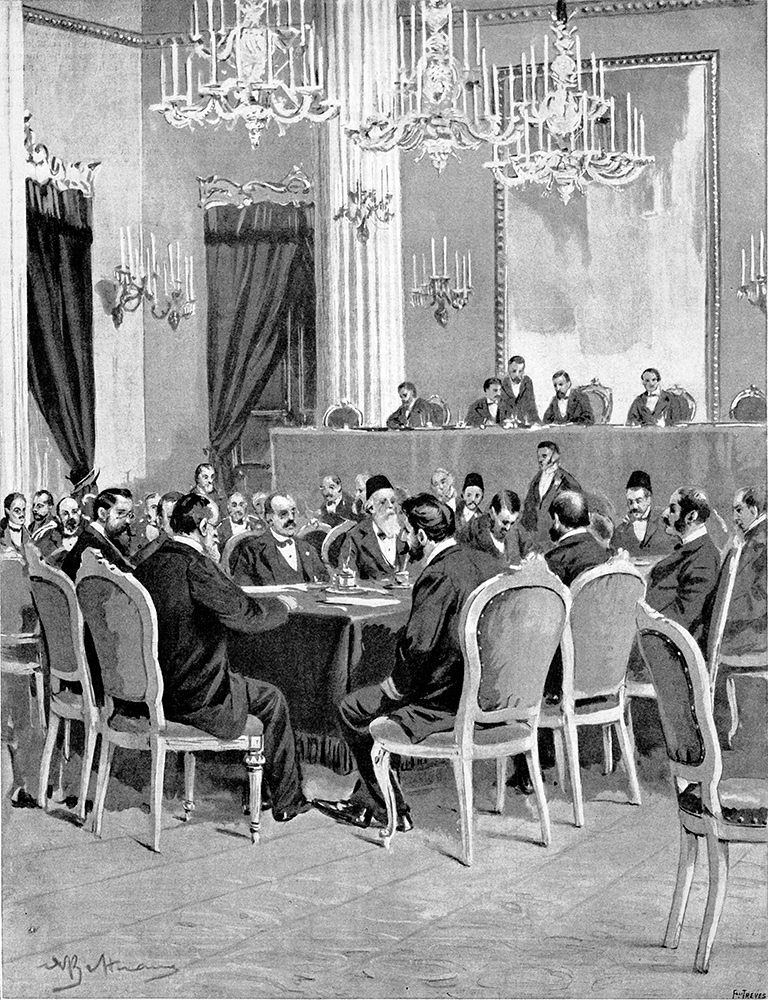

Meeting at the International Sanitary Conference, Venice, 1897, L’Illustrazione Italiana. © DEA / Biblioteca Ambrosiana / Getty Images.

Meeting at the International Sanitary Conference, Venice, 1897, L’Illustrazione Italiana. © DEA / Biblioteca Ambrosiana / Getty Images.

The first of what would be 14 international conferences to improve sanitation took place in Paris in 1851, with 11 European states and the Ottoman Empire attending. Each nation sent scientific and diplomatic representatives to discuss the causes of disease and possible sanitation reforms. Delegates spent six months attempting to come to an agreement on these causes and to determine which diseases warranted quarantine measures. By the end of the conference, however, most states refused to accept the agreement. The conferences often devolved into battles between contagionists and anticontagionists—those who accepted germ theory and those who rejected it—as to the causes and means of communication of cholera, the bubonic plague, and yellow fever. European nations had most of the delegates and most of the power at the conferences, and their main concern was keeping future epidemics away from their borders, rather than helping colonized peoples prevent outbreaks. Four conferences and 30 years later, representation at the conference finally began living up to its “international” moniker. In 1881, delegates from Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Haiti, Liberia, Japan, and China met with European representatives in Washington, DC, where once again not much was decided.

While the conferences weren’t immediately successful in their overarching goals, they were a vehicle for sharing new scientific knowledge. The Italian scientist Filippo Pacini, who theorized that a microscopic bacillus caused cholera during the 1854 pandemic, attended the early conferences and argued with the leading anticontagionist proponents, who argued miasma was the cause. Unfortunately, Pacini would not live to see universal acceptance of his theory. Even the famed German scientist Robert Koch, who’s often credited with the discovery, had to argue with anticontagionists after he proved Pacini correct in 1882.

Nineteenth-century cartoon mocking the various “remedies” for cholera. © The Print Collector / Getty Images.

Nineteenth-century cartoon mocking the various “remedies” for cholera. © The Print Collector / Getty Images.

Despite the failure of delegates to the sanitary conferences to achieve their desired results, the conferences and continued transnational sharing of scientific research laid the foundation for the creation of the World Health Organization in 1948. Unfortunately, the negative effects of progress still plague our world today. Cholera continues to kill tens of thousands every year, mainly in former colonial nations where many do not have access to clean water. Pollution from centuries of burning fossil fuels for industrialization contributes to our current climate crisis. The nineteenth-century Great Stinks and the reform and sanitation movements that followed provide us with insights of how setbacks to progress can still drive collective learning forward. They offer some hope that humanity can continue to learn from these impediments of progress and overcome the challenges we face.

About the author: Bridgette Byrd O’Connor holds a DPhil in history from the University of Oxford and taught the Big History Project and World History Project courses and AP® US government and politics for 10 years at the high-school level. In addition, she’s been a freelance writer and editor for the Crash Course World History and US History curricula. She’s currently a content manager for the OER Project.

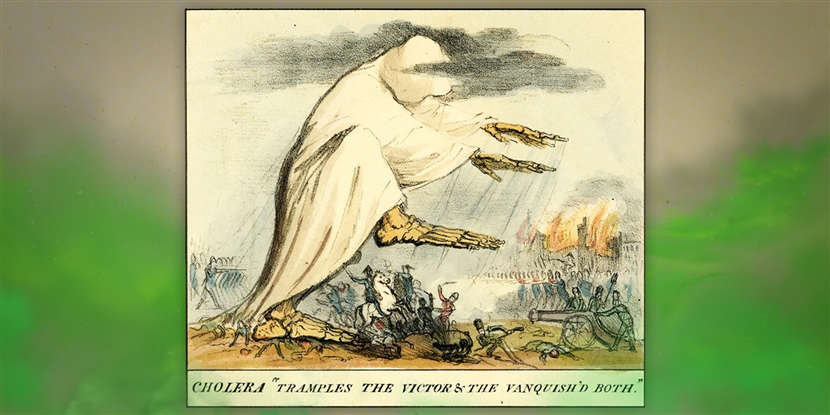

Cover image: Cholera depicted as a skeletal figure giving off noxious fumes as it stomps on Russian and Polish soldiers during the November Uprising (1830–1831). Print by Robert Seymour for McLean’s Monthly Sheet of Caricatures or the Looking Glass, no. 22. © The Trustees of the British Museum

[1] Estimated death rate for India calculated between 18 and 40 million. David Arnold, “Cholera and Colonialism in British India,” Past and Present 113 (November 1986): 118–151. Over the course of multiple outbreaks (1831–1854) deaths from cholera climbed to over 80,000 in the United Kingdom with 36% of these occurring in London. W.S.C. Copeman, “The History of Cholera in Great Britain,” Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine XLI, 165, London, 1947.

[2] Scholars in the Islamic golden age proposed contagion theories, predecessors to the germ theory credited to European scientists such as Louis Pasteur, but miasma theory continued to be popular in the West. For more information on early contagion theories, read “Source 5—Ibn al-Khatib’s Theory of Contagion, c. 1350” in “Source Collection: The Black Death.”

[3] “The intense heat had driven our legislators from those portions of their buildings which overlook the river. A few members, indeed, bent upon investigating the matter to its very depth, ventured into the library, but they were instantaneously driven to retreat, each man with a handkerchief to his nose. … As long as the nuisance did not directly affect themselves noble Lords and hon. gentlemen could afford to disregard the safety and comfort of London; but now that they are fairly driven from their libraries and committee-rooms—or, better still, forced to remain in them, with a putrid atmosphere around them—they may, perhaps, spare a thought for the Londoners.” Friday, June 18, 1858, The Times.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments

-

Gregory Dykhouse

-

Cancel

-

Up

+1

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

-

Bridgette OConnor

in reply to Gregory Dykhouse

-

Cancel

-

Up

0

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Comment-

Bridgette OConnor

in reply to Gregory Dykhouse

-

Cancel

-

Up

0

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Children