By Trevor Getz

My favorite teacher in high school wasn’t actually my teacher. That is to say, when it came time for me to take AP® US history, I was assigned the boring instructor whose students always passed the test, rather than the guitar-playing rebel who inspired his classes to stand up and take action. I ultimately got a 4 on my AP® exam, but I was envious of my peers who instead led a school-wide protest against the lunchtime menu.

But the truth is that now, as an educator, I find that I have modeled myself on the stuffy-but-effective teacher I was assigned back in tenth grade. It’s not that I think passing a test is the metric by which we should judge success. Rather, I admire the way that stuffy guy taught us to set a goal for ourselves, and then to use evidence and a solid methodology to achieve it. I’d like to suggest that this is precisely how we want our students to confront climate change in our social studies classes. And one of the best ways to help them, I think, is to share with them examples of really successful projects executed by other young people.

But where can students find these models? Not in news outlets, unfortunately. Whether online, on the radio, or on TV, most news stories focused on youth activities around climate change feature only the most dramatic, confrontational, and sensational activism. They might lead us to believe that marching and protesting are the only ways to support the effort to stop climate change. But they’re not the only strategies and they’re probably not the most effective ones. After studying more than 70 youth-led climate-related projects, including interviewing some of the participants, I’m impressed by a lot of the community-level, collaborative, thoughtful, and successful work high-school students (and even younger kids) have pulled off. In Climate Project, we’re beginning to feature some of these examples as case studies students can use to plan and model their own projects, but I want to share a few of them with you here, and tell you the lessons I’ve learned from analyzing the whole collection.

Examples of student climate project success stories from cjonline and South Seattle Emerald.

Examples of student climate project success stories from cjonline and South Seattle Emerald.

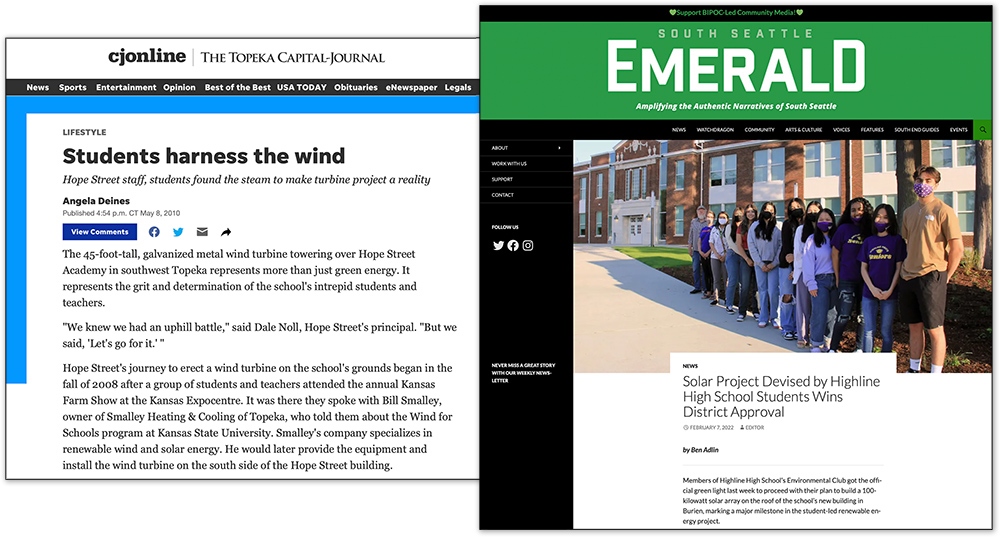

First, let me tell you about a few really great projects focused within the school. In Burien, Washington, Nhua Khuc led her high-school environmental club to successfully get funding and permission to install 225 solar panels. In Topeka, Kansas, a group of students including Kayce Carson, Quincy McCord, and Evanne Wheeler successfully applied for a grant to get a wind turbine installed at their school. Both of these projects are going to be featured in Climate Project as one-page graphic biographies. Students have led other, similar power-generation projects in cities and towns across the country.

Graphic biography of Nhua Khuc. Click to enlarge. By OER Project, CC BY-NC 4.0.

Graphic biography of Nhua Khuc. Click to enlarge. By OER Project, CC BY-NC 4.0.

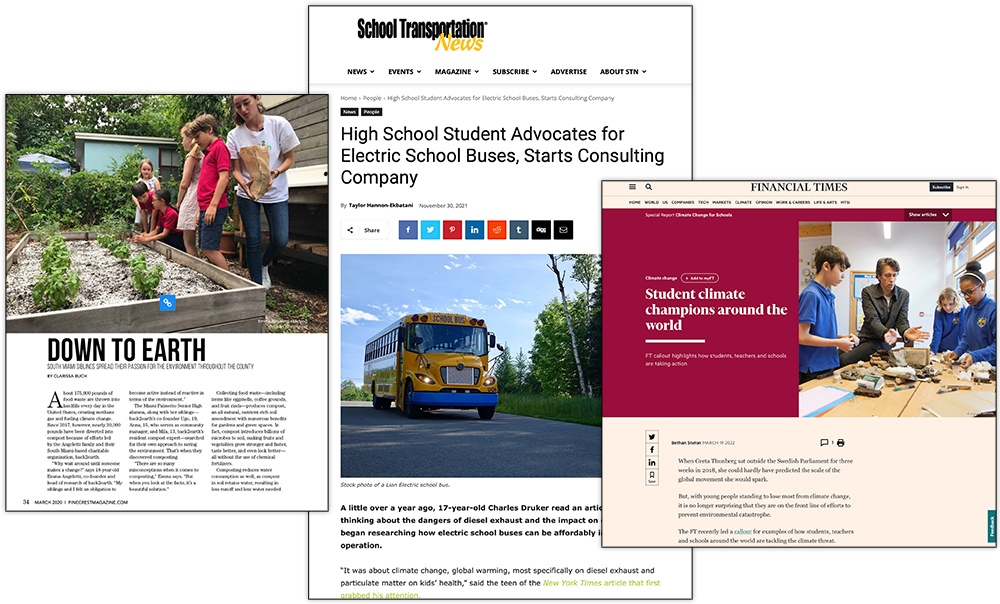

And these power-generation projects are just the beginning. Students are also taking on the problem of greenhouse gas generated by food waste. Ugo and Emma Angeletti, in Miami, Florida, built support for a large-scale composting service to prevent food waste and reduce fertilizer use. By their calculations, they've prevented the release of 180,000 pounds of greenhouse-producing methane gas. In Cambridge, Massachusetts, Charles Druker helped convince his school—and others—to switch from diesel to electric buses. Across the ocean in Kent, United Kingdom, Lily Ray demonstrated how inefficient older buildings on campus were, which prompted the installation of new insulation. She and her peers also started an initiative to install electric-vehicle charging stations on campus.

More examples of student climate project success stories from Pinecrest Magazine, School Transportation News, and Financial Times.

More examples of student climate project success stories from Pinecrest Magazine, School Transportation News, and Financial Times.

What do all these success stories have in common? In my interviews with participants, I’ve found that they all rely on community support. The students I’ve talked to have searched out nonprofit or government agencies as partners. They’ve raised money at farmers markets. They’ve gone door-to-door and presented to fraternal organizations to get support. They’ve worked with neighbors. They’ve appealed to city councils to get planning permission. They’ve educated their peers and parents. In each case, they succeeded through a community effort!

Now, I don’t want to suggest that any of these projects is easy, or that they’re all that’s needed to solve the persistent problem of climate change. The fact is, getting to net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions is going to take change on the global and national levels. But I do want to suggest that community-based projects that focus on the school and surrounding community, that feature educating neighbors and lobbying local leaders, and that slowly build support, can make a difference. All these actions may seem small, but they inspire others. Together, they might make a big difference. They are also the kinds of projects that might be most appropriate for your social studies, civics, or even science classroom.

About the author: Trevor Getz is a Professor of African History at San Francisco State University. He has written eleven books on African and world history, including Abina and the Important Men. He is also the author of A Primer for Teaching African History, which explores questions about how we should teach the history of Africa in high-school and university classes.

Cover image: Students from Highline High School raise funds and find partners for a school solar project at a local farmers market. Photo © and courtesy of Nha Khuc.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,