By Trevor R. Getz

How do you build a climate course for the twenty-first century? One that doesn’t just focus on the science but also helps students engage with the social, economic, and political realities we face? Oh, and that also encourages them to act on what they learn?

When we first began building the Climate Project, we saw that there was already a lot of science-focused climate curriculum out there. A lot of materials were aimed at helping students grapple psychologically with the inevitability of a warmer, less healthy, more dangerous world. We wanted to take a different approach. We wanted students to know that it’s not too late to fight to keep the world from warming perilously, even though it’s going to be really hard, and we’re all going to need to find ways to pull together. We felt students should understand that climate change is more than a science problem, and that the scientists and engineers are going to need help from teachers, lawyers, people in the trades, and community leaders. More than that, we wanted to help students discover pathways to taking meaningful, evidence-based actions to help in that fight.

That’s why we designed the Climate Project to focus not just around social studies, but even more specifically around civics. The course is meant to provide everything a teacher needs to help students engage in the democratic process via productive, responsible, and informed action that is authentic to themselves and their communities.

It turns out that these goals fit the government or civics standards developed by each state pretty well. They also fit the Seals of Civic Engagement that are emerging as requirements for graduation in lots of states–like these in Arizona, Georgia, and California. The Climate Project’s design builds on the typical question a science course might ask—“What is happening?”—by moving to the next step and helping students think through “What are we going to do about it?”

Students in Los Angeles take part in a civics exercise as part of the city’s Youth Council. © Carlos Chavez/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images.

Students in Los Angeles take part in a civics exercise as part of the city’s Youth Council. © Carlos Chavez/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images.

The main way the Climate Project fits a civics framework is that it has students research and rally around a specific solution to a climate change problem. Students get to pick that solution, whether it’s actively reducing food waste at school, helping their community apply for block grants to build charging stations, or educating their peers about climate-related job opportunities. They reach these solutions partly by studying what is effective at reducing greenhouse gases, and partly by asking what solutions authentically fit their community’s assets and values and their own interests. Doing this hard work helps them cut through the anger, misunderstanding, and other obstacles that hold these solutions back at a national level, and it encourages them to take informed action in their school or community.

This civics framework is readily apparent in the three-week Climate Project Extension course. Students begin with an exploration of the problem of climate change. Then they research some possible solutions. In this process, they evaluate the evidence for each proposed innovation or solution, asking questions like, “Which of these strategies will make the biggest difference?” and “Which will work in our community?” Finally, they gather in a summit meeting with their classmates. Here they work out some ideas that are backed by evidence, ideas they can share more widely through informed action.

In the semester-long course, which will launch this summer (2023), the civics approach will be expanded. Students will explore Climate Action Plans from other communities like Whitefish, Montana and Oklahoma City. They’ll see what cities and towns across the country are doing and then figure out which of these things might work in their own communities. Finally, they’ll take informed action—write to legislators, address the school board, or educate their peers.

All this may seem a tall order, but we know kids can help change the world. Not through despair, but through informed, democratic, and civic action. Maybe they can even model the kind of behavior we need kids and adults alike to display in order to face today’s challenges.

About the author: Trevor Getz is a Professor of African History at San Francisco State University. He has written eleven books on African and world history, including Abina and the Important Men. He is also the author of A Primer for Teaching African History, which explores questions about how we should teach the history of Africa in high-school and university classes.

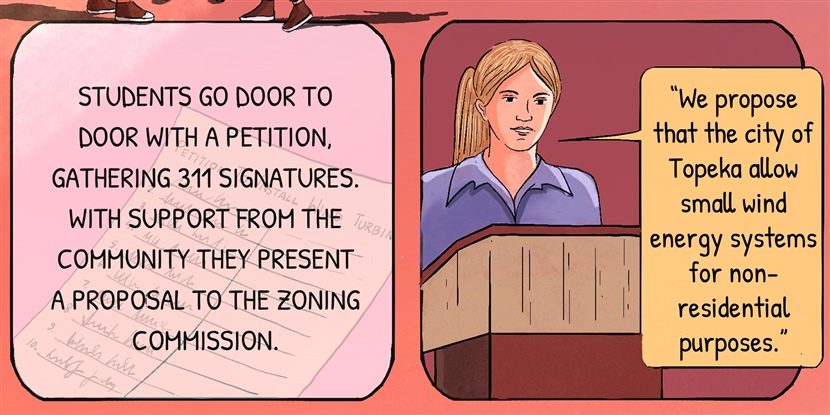

Cover image: Detail from a forthcoming graphic narrative from the Climate Project, detailing a real-world civic project undertaken by students in Topeka, KS to get a windmill installed at their school. In the narrative, students describe the informed actions they had to take to get their project approved.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,