By Rachel Hansen, OER Project Teacher

Iowa, USA

Note: Over the new few months we'll be gradually bringing over some of your favorite articles from the old BHP Teacher Blog. Enjoy this throwback piece, originally posted January 17, 2020.

How close can we get to the Sun? Why does gas cost so much in Europe? If we traded eyeballs, would my idea of purple look different from yours? Is the Moon fake?

I’m bombarded with questions that I cannot answer for what feels like the eleventy-billionth time today, and give the nod to our Class Googlers—the self-appointed research assistants who seek out the answers to our wildest wonderings. On the days that I am exhausted by all of the crazy what ifs, I remind myself that three months ago, there were no questions. None. The fear of asking a dumb question, or sometimes the fear of questioning my authority, silenced all of that beautiful intellectual curiosity. I’ll take the crazy questions any day.

We’ve turned all of our I don’t knows into I don’t know, BUT I know how to find out. It took all of us a while to admit we didn’t have all the answers. And by “we,” I mean me, too.

For too long, the aim of school was to get all of the correct answers. Instead, we should focus on asking thoughtful questions. Curiosity is a habit that can be learned. Lead learning using strategies like these is the way I know to teach it.

1. Teach Students to Be Curious

Albert Einstein said, “I have no special talent. I am only passionately curious.” Let’s teach students to relentlessly pursue their curiosities. Here are some of my favorite ways to encourage students to ask good questions:

World Café: Although World Café is a collaborative dialogue strategy designed for non-educational settings, it’s a powerful learning tool when adapted to the classroom. Students design and lead dialogue around compelling questions that genuinely matter to their lives. Conversation clusters include 4-5 students, and the entire session consists of 3-6 rounds lasting 10-20 minutes each. We’ve used this to troubleshoot class projects, make interdisciplinary connections, and analyze primary documents. Empower students by including them in the design process. They have important questions. Sometimes they just need a little nudge and a safe, structured space to discuss them. Interested in trying this in your classroom? Check out World Café’s Hosting Toolkit!

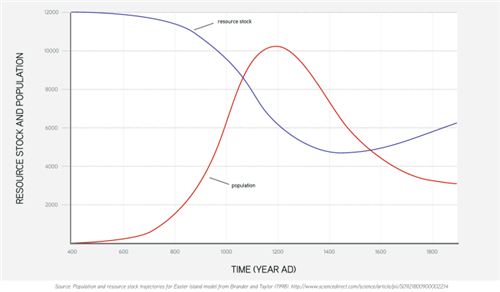

I Notice, I Wonder: We use “I Notice, I Wonder” sentence stems every day in class. I post an incredibly interesting map, graph, image, quote, or question, and then try to find a way to make it even more intriguing. A map without a title, for students to name. A map without a key, for students to label. A graph of population and resources on Easter Island. An aerial image of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. Juxtaposed maps of energy consumption by country in 1960 and 2010. The goal: Get students wondering about EVERYTHING! If you’re looking for something with more structure, try the Question Formulation Technique (QFT).

From the “Easter Island Mystery” assignment in Lesson 1.3 of the Big History Project.

From the “Easter Island Mystery” assignment in Lesson 1.3 of the Big History Project.

Empathy Mapping: Teaching curiosity begins with a firm foundation in empathy. The ability to understand the feelings of others requires expert listening skills. Like curiosity and creativity, listening is a skill that can be learned. Empathy mapping provides students with a structure for close listening. The strategy is often used by design groups to better understand the needs of their clients; however, it’s also a perfect tool for helping students listen to and interpret the feelings, attitudes, and beliefs of others.

- Empathy map template and rubric

- Lesson plan from Stanford University’s d.school

- Activity from IDEO’s Tom Kelley

2. Embrace the Google

Googling is an art form. Skilled question formulation leads to insightful answers. Although these are digital natives we work with, they’re often left frustrated by the amount of junk that clutters their Google search results. We spend a lot of time refining our Googling skills.

Because “click bait” is so tempting, we also spend considerable time confronting our confirmation biases so that we don’t fall into the trap of only seeking out information that confirms our current world view. Even when faced with objective facts, we tend to gravitate toward those that fit our preconceptions. On top of that, social media acts as a sort of echo chamber, often filling our feeds with opinions that reinforce and strengthen our own beliefs.

Facts can be hard to find. They seem to be extra slippery these days. Embracing the Google search as part of being a lead learner means that you’ll spend a good deal of time helping students decipher what information they’ll need in order to zero in on the answers to those big questions.

3. Make Claims. Test Claims. Repeat.

We make claims in class every day. We write them. We look for them in writing, in videos, in podcasts, and in our social media news feeds. We are skeptics, through and through, so we systematically test those claims. And for good measure, we test them again. It’s kind of like the scientific method, but for life. Lead learning is on full blast in this claim-testing process. I am often left vulnerable as I work through an evaluation of a claim in real time with students. I use this Snap Judgment activity to model my thought process and help students sharpen their own critical thinking skills:

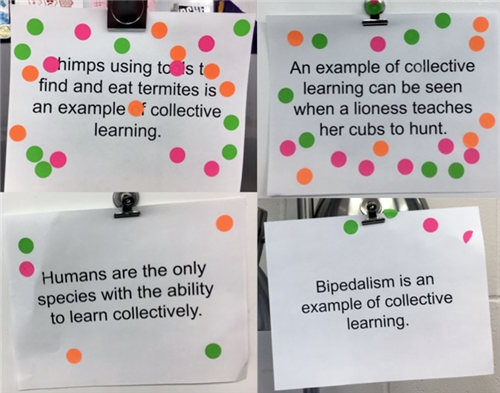

Snap Judgment: We’ll often start a unit by doing a Snap Judgment activity, in which we post on the walls 7-8 claims related to the content we’re studying. Students move around the room in small groups of 3-4, placing a sticker on the claims that pass their claim-testing round. Students run each claim through the filter of four claim testers: authority, intuition, evidence, and logic.

The four claim testers, from the Big History Project.

The four claim testers, from the Big History Project.

A snap judgment activity on collective learning from our world cultures class.

4. Get Comfortable with Not Knowing

Learning is by far the best part of teaching. Learning is not the acquisition of facts. Learning is understanding how those facts came to be. We’ve got to lead the learning charge and walk alongside students in their journey to pursue knowledge. Besides, how much fun would it be to figure out how many golf balls could fit inside the Burj Khalifa?

About the author: Rachel Hansen is a high school history and geography teacher in Muscatine, IA. Rachel teaches the BHP world history course over two 180-day semesters to about 50 ninth- through twelfth-grade students each school year.

Header image: Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive, Big Bend National Park, United States. Photo by Kyle Glenn on Unsplash.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,