By Noah Ramage

When you think of Native Americans resisting European foreign invasion, what do you picture? Do you see men on horseback encircling a federal outpost? Do you see women leading their communities while absent warriors raid deeper and deeper into frontier settlements? Do you imagine a slippery Indigenous “guide” misleading explorers in the a wilderness, or do you see former enemies within Native America using diplomacy to unite against the newer, greater threat? Well, if you do see these things, you’ve got the right idea, but there has also always been more to Indigenous resistance than war and deception; resistance can take many forms.

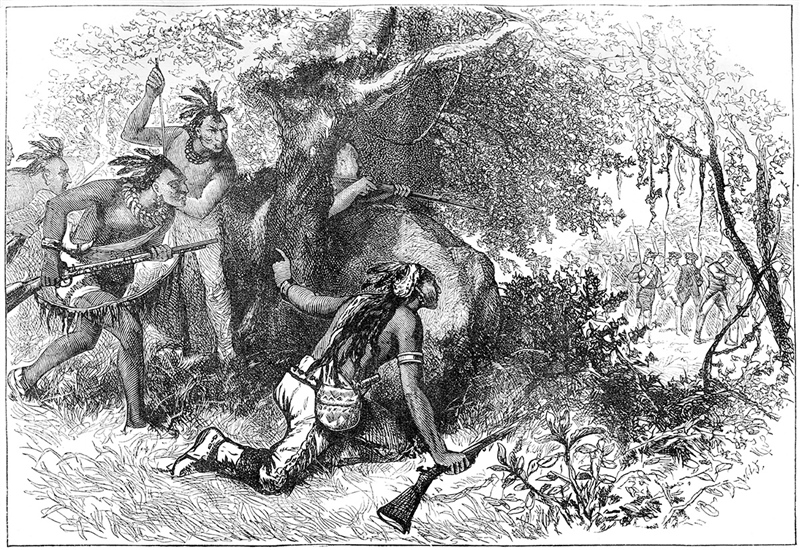

A print from an 1874 history book, Cassell's History of the United States, depicts the “Treachery of the Cherokees.” © The Print Collector / Getty Image.

A print from an 1874 history book, Cassell's History of the United States, depicts the “Treachery of the Cherokees.” © The Print Collector / Getty Image.

State-Building as Resistance

Many Native peoples responded to American state-building with their own state-building. These Indigenous republics were very successful at keeping their ways of life intact, and a great example of this can be found among the Cherokee. The College Board suggests that the Cherokee are an illustrative example in Unit 6 of AP® World History: Modern, as students explore Indigenous responses to state expansion during the long nineteenth century.

In 1794, in response to the formation of the United States, the Cherokee of the American southeast united as a people under one principal chief and one assistant principal chief—analogous to the US president and vice president—along with a National Council—the legislative branch. The Cherokee soon created a police force and banned the cultural practice of revenge killing. Year after year, new laws were passed, and with these laws, a new Indigenous state began to take shape.

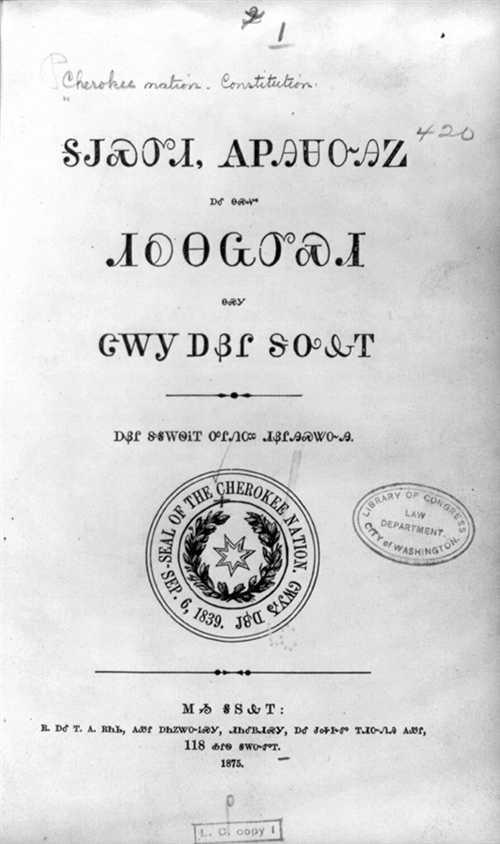

Cherokees correctly referred to this new state as a republic, which gained the sympathy and respect of many white Americans in the northeastern United States. Going further, in 1817, Cherokees changed their National Council into a bi-cameral legislature, splitting the chamber into two separate law-making houses—just like the United States. In 1827, traditionalist full-bloods and acculturated mixed-bloods both ratified the first Cherokee constitution, creating their own Cherokee Nation Supreme Court in the process. The Cherokee were determined to create an independent, Indigenous democracy in the heart of the south.

The title page of the Constitution and Laws of the Cherokee Nation in Cherokee with the seal of the Cherokee Nation, published in 1875. Public domain.

The title page of the Constitution and Laws of the Cherokee Nation in Cherokee with the seal of the Cherokee Nation, published in 1875. Public domain.

Forced Removal

Southerners—particularly slaveholders—were determined to destroy this state. Their state governments held competing claims to Cherokee territory, and they badly wanted to expand their plantations into these cheap, fertile lands. They demanded the federal government remove the Indigenous nations of the South and relocate them to the American West, which was sometimes referred to as the Great American Desert. Deeply attached to their ancestral lands, Cherokee used all the tools of a democratic people—lobbying, petitioning, voting, debating, and litigating—to prevent their removal, but they were unsuccessful. Despite an outpouring of support from northern states, and even though the US Supreme Court ruled against the southern states’ attack on Cherokee sovereignty, the Cherokee would be forced to march what became known as the Trail of Tears into what is today eastern Oklahoma.

All Cherokees were forced into the West against their will, but many had two burdens to bear. Enslaved Black Cherokees and Africans were forced to partake in the removal by their Cherokee masters. They were enslaved and evicted all at once, and neither the first Cherokee constitution (1827) nor the second (1839) would offer them any relief. Only the US Civil War would liberate them.

Cherokee women also suffered a loss of power with the rise of the Cherokee republic. Under precolonial systems, women had played an important part in Cherokee government and politics. Under the new systems, however, they would be pushed out of leadership roles and disenfranchised entirely. For all its achievements in protecting Indigenous sovereignty and traditions, the Cherokee republic was extremely oppressive toward both Black Cherokees and women.

A Resilient Republic

Remarkably, when the Cherokee arrived in their new lands, they did not abandon the democratic experiment. The United States had used its own democracy to brutally remove Native nations, but Cherokees still believed in republicanism. They formed a new government shortly after their arrival in the West, and this second republic would soon become far more powerful and populous than the first.

The Cherokee achieved this by focusing on their own government, now operating in the American West. The Cherokee divided their new nation into nine districts (analogous to states). Each district had its own elections, representatives, courts, and bureaucracies, and all were subservient to the national government. If you were having trouble with white intruders on your land, you would have to contact your district solicitor, who might then contact the principal chief, who might in turn ask a federal agent to authorize the removal of the intruders. Just as in most governments, there was a chain of command, and Cherokee officials from the local to the national level understood the importance of a well-tuned administration.

This new government boasted many accomplishments. The Cherokee erected over 100 public schools all over their country, but prized their Male and Female Seminaries most of all. These two prestigious schools mostly educated the children of elites before shipping them off to American universities such as Dartmouth College. Other graduates went straight into government and helped to create the Orphan Asylum, the National Prison, the Insane Asylum, and a new capitol building. These offices created safety nets, enforced the law, and encouraged national pride—all on Cherokee terms.

Photograph of the 1902 graduating class of the Cherokee Female Seminary, taken in 1902 in Tahlequah, the capital of the modern Cherokee Nation and the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians. © Jennie Ross Cobb / Oklahoma Historical Society / Getty Images.

Photograph of the 1902 graduating class of the Cherokee Female Seminary, taken in 1902 in Tahlequah, the capital of the modern Cherokee Nation and the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians. © Jennie Ross Cobb / Oklahoma Historical Society / Getty Images.

During the 1880s, the Cherokee National Treasury collected more money than it ever had before. Its economy was healthy, its people were prosperous, and its position within the United States seemed to only grow stronger. During this period, many white Americans held a double standard: They favored harsh policies toward many Indigenous peoples but thought that the Cherokee and other “civilized” nations should be left alone. For several decades, Indigenous republicanism shielded the Cherokee from interference.

Denationalization

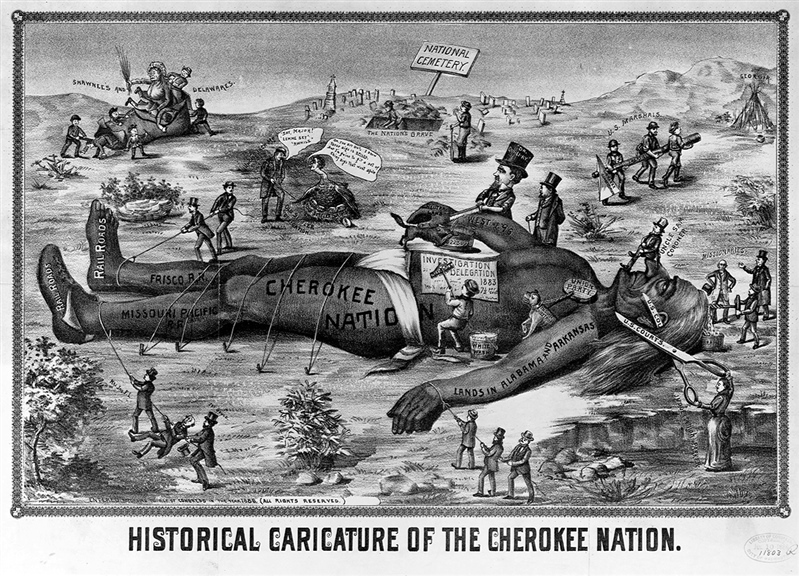

During the late 1890s, perhaps as part of a trend in the rise of American imperialism, the United States became determined to get rid of Indigenous republics—a process called denationalization. In 1897 and 1898, Congress passed laws to abolish Indigenous courts, undermine Native legislatures, and force the Cherokee to negotiate the end of their own national existence.

Political cartoon depicting a giant Cherokee Indian being tied down and destroyed, symbolizing the Cherokee Nation being destroyed by railroad companies, US courts, and US marshals. © Library of Congress / Corbis / VCG via Getty Images.

Political cartoon depicting a giant Cherokee Indian being tied down and destroyed, symbolizing the Cherokee Nation being destroyed by railroad companies, US courts, and US marshals. © Library of Congress / Corbis / VCG via Getty Images.

This process was mostly—but not entirely—successful. Oklahoma became a state in 1907, and most Americans assumed that they had successfully eradicated the tribal governments. During the 1970s, however, the Cherokee Nation sprung back to life with a third constitution. And in 2020, the US Supreme Court ruled that Congress had never fully abolished these governments at all, which meant that these Indigenous republics had quietly remained alive for the entirety of the twentieth century.

Today, this centuries-long experiment in Cherokee republicanism continues. So was this a success? Was Cherokee state-building a good strategy for resisting an invasion? Have your students consider the different forms of resistance employed by the Cherokee—and by other Indigenous nations. Were some more effective than others? Why or why not? What primary sources might help us answer these questions? Share examples you use to teach about resistance in our teacher community.

About the author: Noah Ramage (Cherokee Nation) is a PhD candidate in history at the University of California, Berkeley.

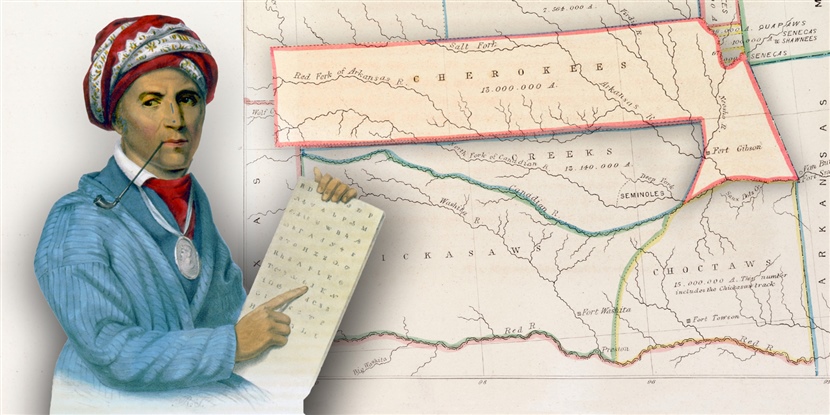

Cover image: Composite image: Sequoyah holding Cherokee alphabet. In 1821, he completed his independent creation of the Cherokee syllabary, making reading and writing in Cherokee possible. © Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images. Map compiled and drawn by soldier-artist Captain Seth Eastman (1808-1875) of the US Army, showing the various tribes and language groups in what is now Nebraska, Kansas and Oklahoma. © SSPL/Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,