By Eman M. Elshaikh and Farhad Imam

As human societies have changed, so too have the diseases that afflict us. In Unit 9 of the AP® World History Modern Course and Exam Description, students are expected to understand how the changing nature of diseases has shaped human societies and how the development of our societies changed the nature of the diseases we face. One of the diseases that the College Board lists as an illustrative example is Alzheimer’s disease, a fatal, progressive, neurodegenerative disorder that has been described as the public-health challenge of our time—the plague of the twenty-first century. In this blog, we’ll explore why. We’ll also explore some of the latest advancements in understanding the disease with Dr. Farhad Imam, Director of Health and Life Sciences at Gates Ventures.

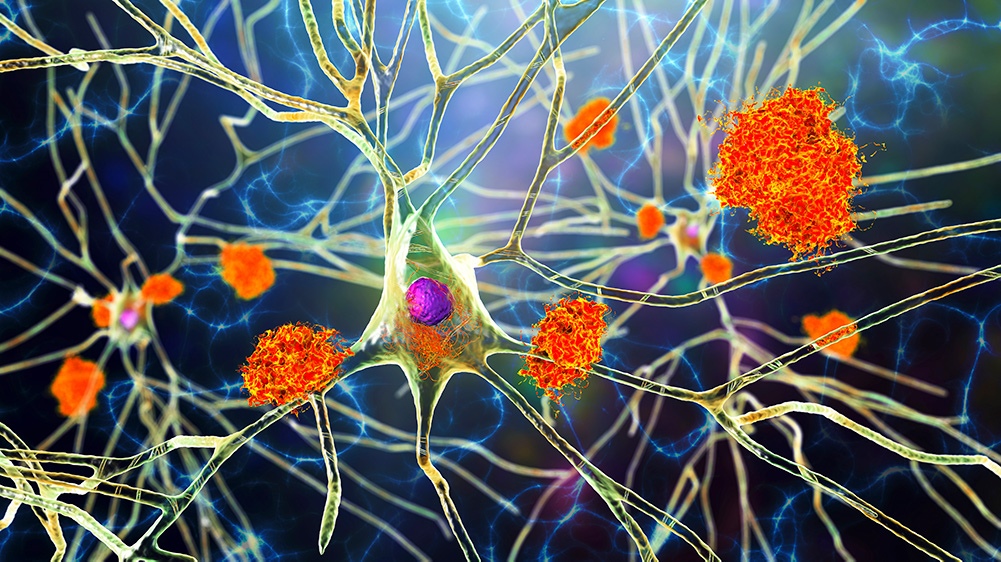

According to Dr. Imam, Alzheimer’s disease emerges “when brain cells—neurons—in particular regions get sick and stop functioning normally. Their job is to process information and send signals to each other, similar to electronic circuits. But when they are unhealthy, they get ‘glitchy,’ and can either stop sending signals or send them inappropriately—somewhat like a short circuit.” This can lead to impairment of memory, word-finding, and spatial recognition.

Alzheimer’s disease causes a great deal of suffering, and it’s an urgent public-health concern for our time. But why is it the plague of this century?

Premodern history of dementia

Alzheimer’s disease got its name in 1906, but it’s been around a lot longer than that. Dementia, which is the main symptom of Alzheimer’s, has been described in various ways by different cultures since antiquity.

Historically, societies have associated dementia with various organs and causes. Yet, in general, scholars and doctors have long observed that cognitive decline is often associated with old age. Ancient Egyptian writings show that people believed memory loss came with old age. And in Ancient Greece, Pythagoras divided life into seven periods, the last of which, he argued, caused the mind to weaken. We even find references to dementia in a Han-dynasty-era book and a first-century Roman medical treatise by Cicero! In the medieval period, the Persian polymath Avicenna contributed to our early understanding of different forms of dementia and their causes.

So, we can see how, for millennia, societies worldwide have assumed that dementia was an ordinary result of aging. So why all the alarm today? Why do some scholars predict an Alzheimer’s epidemic in 2050? What’s changed?

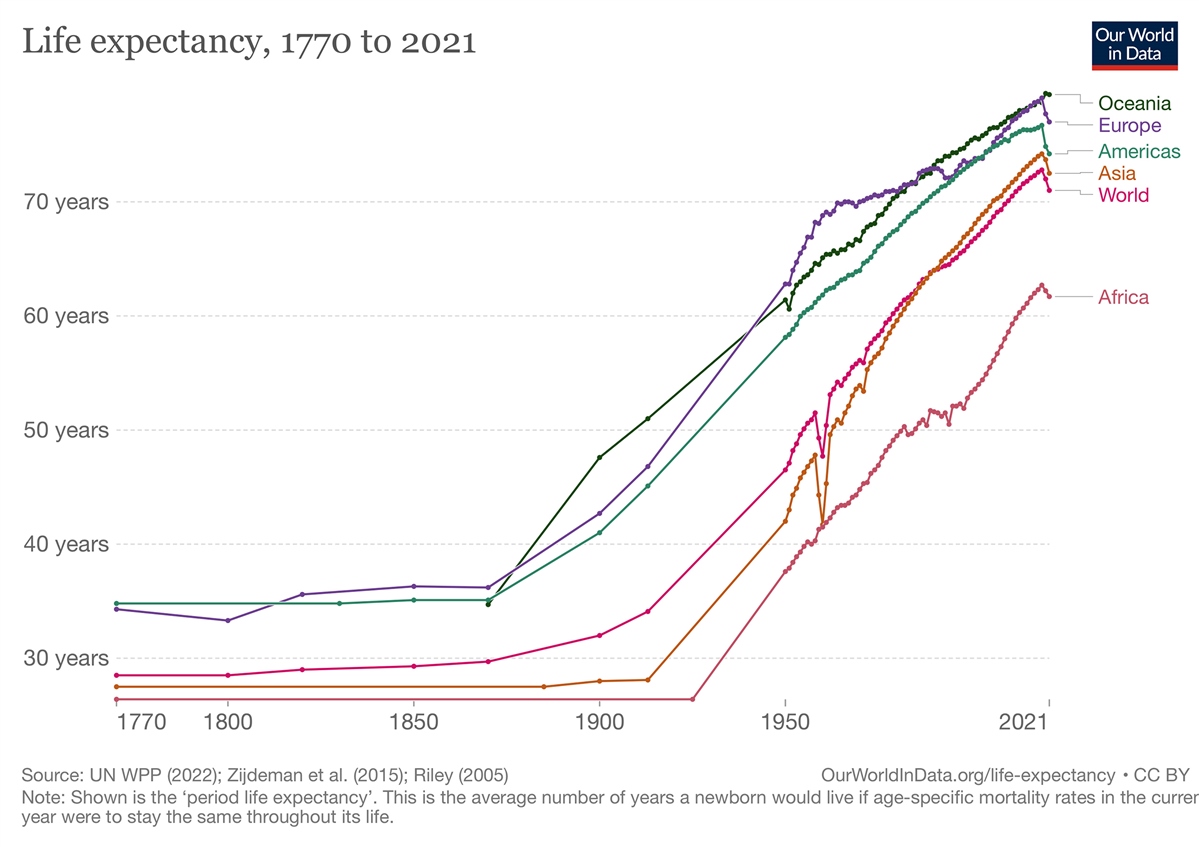

Longer life spans

Well, the demographics of human societies have shifted radically in the last 100 years. For most of human history, life expectancy wasn’t much longer than the age of reproduction. But during the twentieth century, life expectancy in every region of the world rose precipitously. Despite the violence of two world wars, the 1918 pandemic, and crimes against humanity, we started living longer.

We can give thanks for our increased life expectancy to scientific advancements and public health measures, particularly in wealthy communities. Much of the improvement comes from lower infant and childhood mortality. But it also has to do with the advent of antibiotics and vaccines, which, coupled with better hygiene measures, drastically reduced deaths from malaria, tuberculosis, polio, and smallpox. That’s great, right?

Well, yes. Of course. But the paradox of winning the fight against all these diseases is that many humans now regularly live long enough to develop other diseases associated with old age, like Alzheimer’s. The increasing prevalence of diseases associated with longevity is transforming our societies.

Increased life expectancy is directly linked to the increased prevalence of Alzheimer’s. The risk of Alzheimer’s doubles every 5 years a person lives past 60. About 1 in 6 people over 80 and 1 in 3 people over 90 are likely to develop it. This dramatic and rapid increase in average life span can’t be overstated. While human life expectancy gradually increased on an evolutionary timescale, recent increases have occurred in mere decades! To drive the point home: the average Northern European living in 1900 had a life span closer to a hunter-gatherer than to her descendants living in 2023.

Today, 55 million people suffer from Alzheimer’s and other dementias. In the United States alone, there are six million people with Alzheimer’s. By 2050, researchers predict this number will more than double. We haven’t solved the problems of how to diagnose, treat, and care for patients with Alzheimer’s, and these issues will only intensify with time.

The science of Alzheimer’s disease

Dementia has affected humans for thousands of years, and we’ve known about Alzheimer’s disease since 1906. Yet, only in the last 50 years has there been attention to it as a public-health issue and the leading cause of dementia. Alois Alzheimer (1864–1915), after whom the disease was named, received no questions when he presented his findings to his fellow scholars. For decades after, fairly little was said about the disease in scientific journals. It wasn’t until the 1960s and 1970s that researchers recognized that Alzheimer’s disease was becoming an increasingly common cause of death in many places, at which point research started to intensify.

Today, there are some promising solutions on the horizon. A new class of drugs that target abnormal aggregations of amyloid protein (which makes up the characteristic plaques in the brain associated with Alzheimer’s) are in development. As Dr. Farhad Imam notes, “The good news is that lecanemab, an antibody-based drug that targets small clumps of amyloid protein, recently reported the successful slowing of cognitive and motor decline in Alzheimer’s patients with moderate impairment. This was a landmark clinical trial for the field and comes after decades of negative results in over 200 previous clinical trials.”

Nerve cells affected by Alzheimer’s disease © Kateryna Kon via Getty Images.

Nerve cells affected by Alzheimer’s disease © Kateryna Kon via Getty Images.

There are still many problems to solve, both scientific and social. Scientifically speaking, Dr. Imam explains, “What’s puzzling is that many other anti-amyloid antibody or small molecule therapies have not shown the same effect as lecanemab…. The faster we get to the bottom of why one [lecanemab] worked, and why another [solunezamab] didn’t, the faster we can be on the right track for better and more personalized therapies.” A major barrier for researchers who want to help solve this puzzle is data access: most clinical-trial cognitive and imaging data is difficult to obtain and combine with results of other studies in larger meta-analyses. In order to realize the promise of big data in Alzheimer’s patient data, we must not only get better at sharing patient data safely and with appropriate privacy, but also faster at processing the thousands of cognitive tests, images, and biochemical findings that make up these large data sets. So, although we need to keep researching in order to treat Alzheimer’s, diagnosis is also a challenge. According to Dr. Imam, we still don’t have great ways to safely or easily access brain tissue and spinal fluid in large numbers of patients, and we haven’t yet identified reliable biomarkers of Alzheimer’s that can be measured in the blood. Digital biomarkers that measure content or quality of speech, or wearable sensors that detect patient movement are also being closely investigated—on their own and in combination with biochemical and imaging data—and are a promising extension of our current set of diagnostic tools.

We also face social challenges: drugs that treat Alzheimer’s are administered through IVs, which are resource-intensive to administer at clinics or from visiting home health workers. There are also equity challenges when it comes to participating in clinical trials in the first place since, as Dr. Imam explains: “Patients are required to undergo costly imaging studies—sometimes multiple MR and PET scans—to qualify for enrollment and for continued participation in clinical trials featuring the latest drug regimens. This increases cost and creates barriers to access, especially in rural and low-income regions. However, new technology is also creating solutions for access as small, mobile MR machines have recently been approved for patient use. They use artificial intelligence to enhance lower-resolution images from lower-power machines and have the potential to perform imaging studies at rural or home settings at a fraction of the cost of conventional imaging done at centralized health centers.”

Despite these challenges, Dr. Imam is hopeful, saying, “we now are on the map with one effective drug—lecanemab. This groundbreaking finding has galvanized the field, as we have found a positive signal for the first time. Now, we need to build on that signal to further amplify its effect via better drugs—including combination therapies with other existing or novel drugs of the future—and better diagnostics to identify disease subtypes and inform personalization of therapy to optimize patient-specific response.”

Drugs of the future are necessary for an aging population, and as global life expectancy increases, we’ll need to invest in solutions that prepare us to care for people suffering from diseases like Alzheimer’s and others associated with longevity. The illustrative example of Alzheimer’s disease can help your students understand historical developments in the “Humans and the Environments” theme of the AP World History course. It also provides an opportunity for students to reflect on other societal transformations that have made other diseases more or less prevalent throughout human history.

About the authors:

Eman M. Elshaikh is a writer, researcher, and teacher who has taught K–12, undergraduate, and graduate students in the United States and in the Middle East. She teaches writing at the University of Chicago, where she also completed her master’s in social sciences and is currently pursuing a PhD. She was previously a World History Fellow at Khan Academy, where she worked closely with the College Board to develop a curriculum for AP® world history.

Farhad Imam is a physician-scientist with clinical and research expertise in brain injury and neuroprotection. He spent his early career in academia after finishing training at Stanford and Harvard, and it was during a sabbatical from UCSD with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation that he fell in love with big philanthropy and the Seattle area. He has spent the last 7 years working on diagnostic and therapeutic discovery in the Gates ecosystem, first for global health priority disease at the foundation, and more recently on Alzheimer’s Disease and other neurodegenerative diseases at Gates Ventures.

Cover: Composite image: Photo of lonely senior woman sitting at a table and thinking. © ciricvelibor / E+ / Getty Images. Watercolor painted leaf plant set, © vector_corp / freepik.com.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,