Trevor R. Getz, WHP Team

San Francisco, USA

What’s in a name? Somewhere between 1493 and 1495 CE, the disease we know as syphilis began to spread rapidly across Europe. When a person became infected, first they developed sores, then a rash, sore throat, a fever, and eventually such terrible symptoms as brain damage and blindness. Nobody really knew where it had come from (there are still debates today!), but the Italians quickly blamed the nearby French, calling it morbus gallicus—the “French disease.” The English, who had a long-standing feud with the French, happily adopted the name. But many people called it “the Spanish pox.” The name stuck, partly because it was convenient to blame the disease on Christopher Columbus’s Spanish crews, returning from the Americas.

The naming of disease has long been a cultural and political practice, a convenient way of deflecting blame from one’s own society or government. Another example is the Spanish flu, our usual name for the influenza pandemic that swept the globe from 1918 to 1919, killing as many as 50 million people. It got that name purely because the Spanish press was willing to report its early spread among their population, while other countries hid the disease. Many of those other countries were at war, and didn’t want to alarm their already exhausted populations, but Spain was neutral. Unfortunately, the Spanish were blamed by the very countries that were hiding their own failure to act![2]

The naming of disease has long been a cultural and political practice, a convenient way of deflecting blame from one’s own society or government. Another example is the Spanish flu, our usual name for the influenza pandemic that swept the globe from 1918 to 1919, killing as many as 50 million people. It got that name purely because the Spanish press was willing to report its early spread among their population, while other countries hid the disease. Many of those other countries were at war, and didn’t want to alarm their already exhausted populations, but Spain was neutral. Unfortunately, the Spanish were blamed by the very countries that were hiding their own failure to act![2]

If you think about it, geography and populations are often used to name diseases. Lyme disease was named after a town in Connecticut. MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) was first reported in Saudi Arabia. Ebola is named after a river in Central Africa. But these are often not the places the disease originated. At the time it was identified, Lyme disease sufferers lived all over the eastern United States—there just hadn’t been a name for the disease before. Although no one knows for sure, the Spanish flu may have actually started in Kansas.

Can the choice of names actually be harmful? Giving place names (or the names of communities or groups) to diseases may seem useful, but there are a lot of problems with this approach. First, those names don’t actually help us to identify why the diseases broke out, which in most cases is more useful information. If, for example, a disease crosses over from animals to humans because of the way we factory-farm our meat, wouldn’t it be more useful for the disease name to reflect that problem? If it comes from bad sanitation, shouldn’t the name tell us that? That might help people to act better in the future to avoid outbreaks of those diseases, or to slow transmission. If there were an outbreak of a disease called the “dirty smartphone disease,” wouldn’t you be more likely to wash your hands after using your phone?

Naming diseases after places or people has another negative impact—it scapegoats a population, and it fuels discrimination and persecution, especially where it already exists under the surface of society. As in the case of syphilis, people often blame others for diseases that are difficult to understand and threaten peoples’ lives. In fourteenth-century Europe, Jews were inaccurately blamed for spreading the Black Death, partly because some religious practices having to do with cleanliness (especially around the Jewish holiday of Passover) helped keep disease-causing rats away. As a result they suffered fewer deaths in comparison with other groups. Angry crowds in the city of Erfurt, Germany, attacked and killed hundreds of Jews, and in other places they were similarly persecuted. Less dramatically, Mexican-Americans in 2009 found themselves subject to racial discrimination when some newspapers labelled the H1N1 influenza virus the “Mexican flu.”

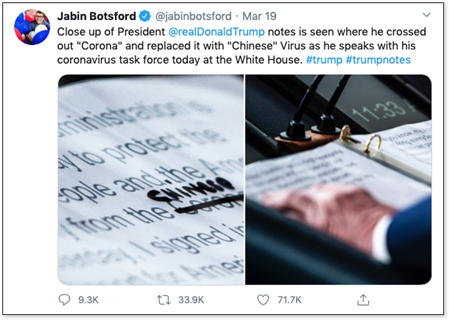

In 2020, we face a deadly virus called SARS CoV-2, which causes a disease known as COVID-19. On Wednesday, March 18, 2020, United States President Donald Trump called this virus the “Chinese Virus.” He argued there was nothing wrong with doing so. “It’s not racist at all. No, not at all. It comes from China, that’s why.”[3] Some journalists, including the opinion editor of USA Today,[4] have agreed that labeling it the “Chinese coronavirus” or the ”Wuhan virus” is fine. But it does seem to have led to a rise in racist attacks, verbal and physical, on people of Chinese or Asian descent in Europe and the United States.[5] It has also hurt business at Chinese restaurants, affecting people’s livelihoods. It may also create problems at a geopolitical level. President Trump’s words have drawn angry responses from China’s Foreign Ministry, and within China rumors are spreading that the disease really started with US military visitors. This has resulted in diplomatic tensions at a time when we should probably all be cooperating with each other.

Close up of President @realDonaldTrump notes is seen where he crossed out "Corona" and replaced it with "Chinese" Virus as he speaks with his coronavirus task force today at the White House. #trump #trumpnotes pic.twitter.com/kVw9yrPPeJ

— Jabin Botsford (@jabinbotsford) March 19, 2020

That’s why in 2015 the World Health Organization adopted guidelines that state disease names no longer single out places, species, or human groups defined by their sexual, religious, or cultural identity. That’s why officially this virus is the SARS CoV-2. It’s named for its symptoms (severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS), its shape (corona-shaped) and the fact that it is the second of its type (2).

But while official naming guidelines have changed, actual human practices change more slowly, and we are still using a variety of names, from “Wuhan virus” to “China virus” to “COVID-19” to “coronavirus.” Maybe each of us should stop and think: What am I calling this disease? What are the implications of that name? How is it changing how I think about the disease, and how I act?

About the author: Trevor Getz is a professor of African and world history at San Francisco State University. He has been the author or editor of 11 books, including the award-winning graphic history Abina and the Important Men, and has coproduced several prize-winning documentaries. Trevor is also the author of A Primer for Teaching African History, which explores questions about how we should teach the history of Africa in high school and university classes.

Header image: Dr. Rhonda Flores labels protein samples at Novavax labs in Rockville, Maryland on March 20, 2020, one of the labs developing a vaccine for the coronavirus, COVID-19. © ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS/AFP via Getty Images.

Body image: German artist Albrecht Durer’s 1496 image of a man with syphilis. © Print Collector / Getty Images.

Sources

[1] Ruben D. Rumbaut, “The Great Pox: The French Disease in Renaissance Europe,” Journal of the American Medical Association 278, no. 5 (1997):440, doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03550050104045.

[2] Laura Spinney, “Who Names Diseases?” Aeon, May 23, 2017. https://aeon.co/essays/disease-naming-must-change-to-avoid-scapegoating-and-politics

[3] Quint Forgey, “Trump on ‘Chinese Virus’ Label: “It’s Not Racist at All,” Politico, March 18, 2020. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/03/18/trump-pandemic-drumbeat-coronavirus-135392

[4] David Mastio, “No, Calling the Novel Coronavirus the ‘Wuhan Virus’ Is Not Racist,” USA Today, March 11, 2020. https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2020/03/11/sars-cov-2-chinese-coronavirus-isnt-racist-wuhan-covid-19-column/5020771002/

[5] Anna Russell, “The Rise of Coronavirus Hate Crimes,” The New Yorker, March 17, 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/news/letter-from-the-uk/the-rise-of-coronavirus-hate-crimes

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,