By Rachel Phillips

We’re used to associating timelines with history, particularly as a way to visualize when important dates happened in relation to one another—and this is likely what many students assume is the sole purpose of a timeline. And sure, it’s incredibly important to have a chronology of the past and a visual representation of how history unfolds. But let’s dig a little deeper into timelines and periodization—the act of dividing and naming time periods. Periodization allows historians to influence how history stories are both told and interpreted. Take, for example, the traditional periodization of early modern history that many students still learn today, which moves from the Renaissance, Scientific Revolution, and Enlightenment to industrialization. This periodization creates a tidy narrative of progress and human ingenuity that was centered in Europe and that led to our modern world, a narrative known as “the rise of the West.” But as we know, this “rise of the West” periodization doesn’t take into account the numerous contributions of different world-systems, systems that the West learned from, thanks to interconnecting networks of exchange that were in place for centuries. The timelines we choose and the ways in which we label them to create a historical narrative can both highlight and obscure details about the past. The ways we periodize can also help us include voices, stories, and ideas that may have been left out of the narrative.

Periodization is a key tool when it comes to historical inquiry—we must always define our time period in relation to the historical event or process being studied, and so must our students. Without defining time periods, we can’t really expect students to engage in historical thinking practices such as contextualization, causation, or continuity and change over time. Without periodization, we would be swimming around in a big pool of history. Periodizing helps us create swim lanes so we can better understand and organize historical narratives.

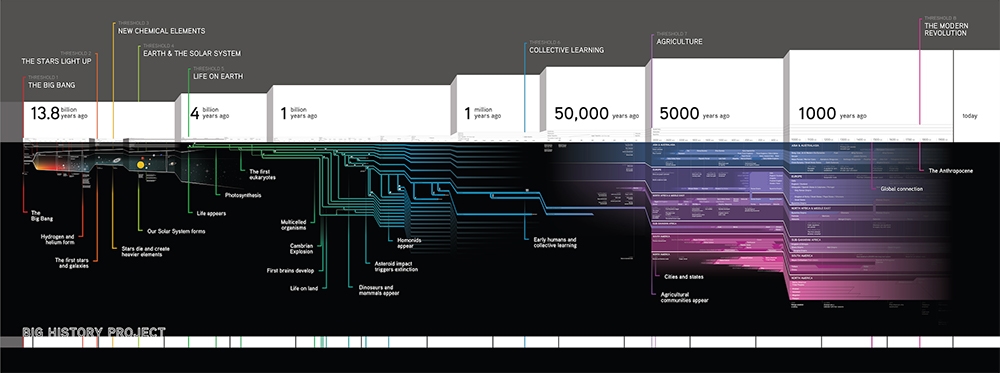

An example of periodization, the Big History timeline. By OER, CC BY 4.0.

An example of periodization, the Big History timeline. By OER, CC BY 4.0.

Periodization is something we encourage you and your students to play with so that they can see the power in this particular practice. In the past year or so, one of my favorite games has been to ask people to periodize COVID for themselves. For example, I think about the following periods from my first year of COVID: there was the “there is only chocolate candy left in the grocery store” period; the “disinfect packages” period; the “let’s bake sourdough and banana bread” period; the “let’s organize every drawer in the house” period; the “jigsaw puzzle” period; and so on. You could ask students to try this activity, or you could ask them to periodize their lives.

There are a lot of classroom activities that can emerge from playing with periodization. For example, you might ask students to pick topics they’re interested in (sports, arts, music, pop culture, and so on) and give them a time frame for examining those topics. Each student could create a timeline or narrative of their topic during that time frame, and then students could compare them to see how looking at different topics over the same period of time can really change the historical narrative. Or you could give students the same topic but assign students different time periods for examining the topic. Then, you and your students could see how stories change once you connect all the time periods.

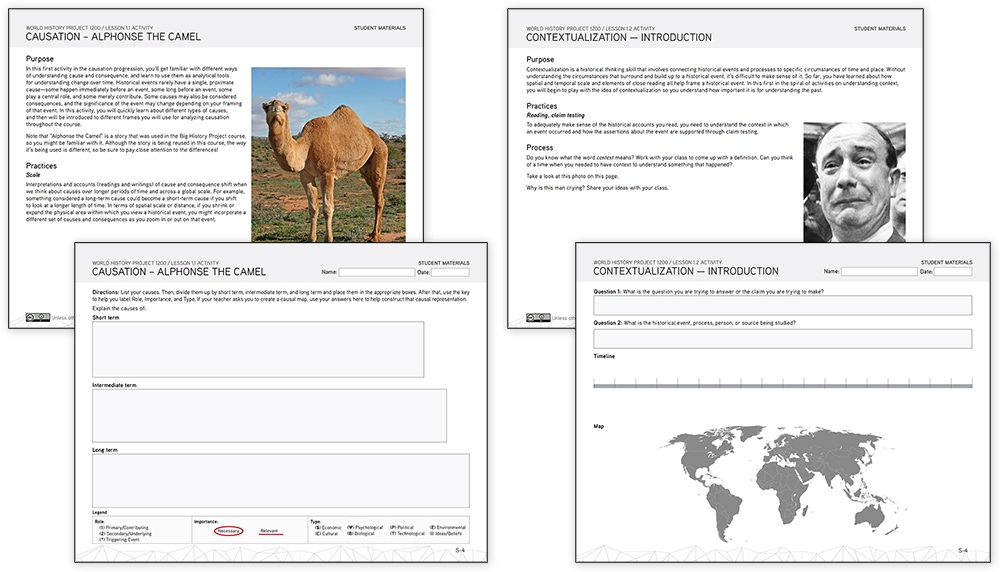

A selection of WHP classroom periodization activities including Causation and Contextualization, By OER, CC BY 4.0.

A selection of WHP classroom periodization activities including Causation and Contextualization, By OER, CC BY 4.0.

You could also ask students to conduct the same causation activity twice, but the second time you’d drastically change the periodization. For example, if you had students analyze the story of Alphonse the Camel over 1,000 years versus 5 years, their analysis would radically change. Short-term causes in the 1,000-year periodization might be long-term causes in the 5-year periodization, and most of the long-term causes for the 1,000-year periodization wouldn’t even show up in the 5-year analysis!

Finally, periodization provides a fantastic opportunity to highlight perspectives that often are overlooked in traditional periodizations. You could take a topic like World War I, but instead of simply focusing on the typical narrative of main causes, battles, and effects c. 1914 to 1918, you could divide students into groups with assigned roles, roles such as government officials, soldiers from European nations, colonial soldiers, women on the home front, women in colonial regions, children, and so on. Each group would then provide a narrative of the war from their perspective, including how each group might periodize the war differently.

There are so many opportunities to play with this, and while the activities are often fun, this is a serious historical practice and concept that should be attended to in all social-studies classrooms. Without periodization, it’s incredibly difficult to make sense of history. How do you dive into periodization in your own classroom?

About the author: Rachel Phillips, PhD, is a learning scientist who leads research and evaluation efforts for OER Project, and also develops curriculum for their courses. She is elementary certified, has taught in K–12 schools, and currently serves as an adjunct professor for graduate courses in American University's School of Education. Rachel was formerly Director of Research and Evaluation at Code.org, faculty at the University of Washington, and program director for National Science Foundation-funded research. Her work focuses on the intersections of learning sciences and equity in formal educational spaces.

Cover image: Composite image, swimming pool with people. © neyro2008 / iStock / Getty Images Plus

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,