By Bennett Sherry, OER Project Team

Maine, USA

I want to tell you a story about cities. It’s a story about the challenges of urbanization, and it’s a story about the modern advances that allowed cities to grow. It’s a story from the bottom up.

If you live in a wealthy nation, you probably don’t think about this story. You conduct your business and flush it down unseen pipes, not worrying about what comes next. But for most of the time humans have lived in cities, “what comes next” has been a question of life or death.

Before the Agricultural Revolution, poop wasn’t a problem. Foragers didn’t have to be too concerned with it. A short walk from their camp would do. If too much waste accumulated, they moved on from their movements.

BHP and WHP courses include activities that ask students to evaluate whether the development of agriculture and cities made life better for humans. Once the Agricultural Revolution allowed people to concentrate in cities, waste became a problem. Middens and cesspits cause disease and pollute drinking water if not managed properly. Cities made life more complicated. Before modern plumbing, the accumulation of human waste was undoubtedly a piece of evidence for the “made life worse” column. Even humanity’s earliest cities, such as Çatalhöyük, suffered these conditions. The remains of children in Çatalhöyük show evidence that they suffered from diseases caused by living in close contact with soil and water contaminated by feces. Agriculture meant that humans had to work harder for longer hours, and now some of them had to be responsible for removing feces.

Just as farming and cities developed independently around the world, so too did methods for managing the final products of the farm-to-toilet pipeline. Ancient cities in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, Mesoamerica, and elsewhere developed latrines and even indoor plumbing. But plumbing wasn’t available for everyone. For many, buckets and open-air defecation remained the norm. We know that sanitation continued to be a problem even in the most powerful societies. For example, in Roman ruins, archaeologists have uncovered some instructive graffiti:

“Twelve gods and goddesses and Jupiter, the biggest and the best, will be angry with whoever urinates or defecates here.”

Other ancient graffiti artists were more direct:

“If you [defecate] against the walls and we catch you, you will be punished.”

In the Roman Empire, toilets were fairly public, and they provided an opportunity for socialization. The trough at the foot of the seats probably carried water intended for cleaning off the communal sponges. By Stefano Bolognini, CC BY 3.0.

Palace plumbing channels in the ruins of the city of Gedi in what is today Kenya. Plumbing was common throughout the Islamic world, including in the Swahili city-states of East Africa. By James de Vere Allen, 1988, Image © and courtesy Archnet.

Eventually, many societies discovered that human waste didn’t have to be a problem. If managed carefully, it could be a resource: night soil. Cities—which typically consume raw materials rather than produce them—could give back to the farms that fed them. In China, night-soil fertilizer from the cities helped fuel farms. And in medieval Japan, night-soil collectors in cities created a profitable market by hauling it to the countryside. In the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, the residents built large artificial islands, called chinampas, in Lake Texcoco. These islands, fertilized with human excrement, were incredibly productive, and Aztec farmers could harvest them several times a year.

A Chinese woman carrying buckets of night soil, nineteenth century. By John Thomson, 1871, CC BY 4.0.

A Chinese woman carrying buckets of night soil, nineteenth century. By John Thomson, 1871, CC BY 4.0.

Night soil itself might have had value in many societies, but almost universally, the laborers who did the work of removing it from cities were less respected. Some societies, like India’s caste system, relegated the people who handled human waste to a lower class of so-called “untouchables.” The English term, night soil, got its name because the cesspit cleaners were required to do their job at night when other citizens wouldn’t have to confront the sights and smells of their labor. And to be fair, cesspool cleaners were often not very careful, and a great deal of waste made its way into roadside gutters or city streets. Historian Donald Reid describes the public attitude toward these workers in Paris: “Their raucous presence in the neighborhood was like a long-delayed fart – unrestrained and unpleasant.”

As cities grew, the same old sanitation problems remained. Not even eighteenth-century Paris—a center of European culture and power—was immune. One French writer described Paris’s “amphitheater of latrines…exuding the most fetid odor on all sides.” He remarked on the “frequency with which blocked pipes cracked, flooded the house, and blasted pestilence through stinking shafts that seemed like the mouths of hell to terrified children.” It’s no surprise, then, that Paris was among the first modern European cities to develop extensive sewer systems and a specialized workforce to maintain them.

The birth of modern sewers in the nineteenth century changed Parisian attitudes. The job of sanitation workers transformed from an unspeakable necessity into a symbol of the modern world. Reid argues that “the sewerman was transformed…into a symbol of man’s mastery of nature.” Parisians hoping to bask in the glow of modernity would pay for tours of the sewers, the contents of which were reused in irrigation. Sewermen were at the forefront of nineteenth-century reform movements—among the first workers to unionize and force labor reforms like the eight-hour workday.

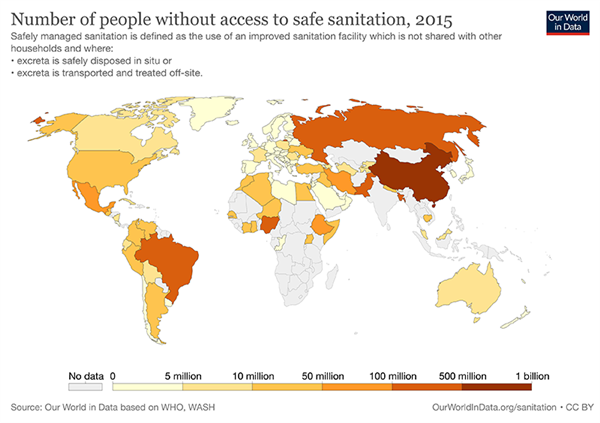

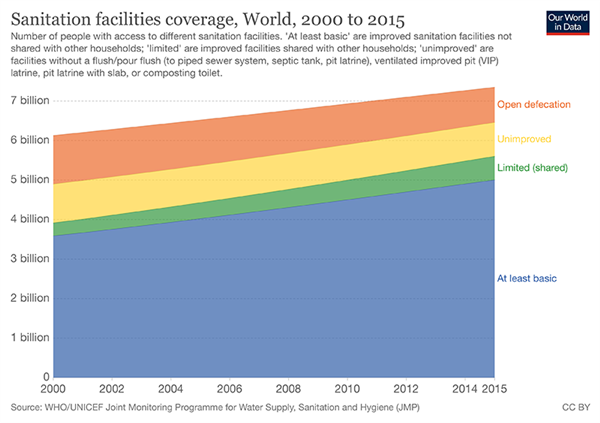

Today, sanitation in cities is as important as ever. With tens of millions living in close proximity, waste disposal is absolutely critical to preventing the spread of disease and ensuring access to clean water. But access to modern sanitation is unequal. As of 2015, open-air defecation is the reality for almost a billion people.

Our World in Data includes these two charts that measure the number of people who lack access to safe sanitation and the type of sanitation methods. Both graphs by Our World in Data, CC BY 4.0.

Our World in Data includes these two charts that measure the number of people who lack access to safe sanitation and the type of sanitation methods. Both graphs by Our World in Data, CC BY 4.0.

As you ask students to consider whether urbanization was a net positive or negative, you might pair this activity with one scheduled later in the course: Dollar Street. Gapminder’s Dollar Street website includes a function that allows students to compare household toilet systems in different countries across income levels. In my experience, when you ask students to reflect on the benefits of the transition to farming and urbanization, they often conclude that it was good. Sure, life was tough for ancient city-dwellers, but now I get running water, smartphones, and antibiotics. And they’re sort of right. Modern advances have pulled billions out of poverty. However, as many as 4.5 billion people still lack access to safe sanitation. The poorer end of Dollar Street’s toilets can help students understand that many of the challenges that faced city-dwellers thousands of years ago still exist today. How many neighborhoods are threatened by middens, cesspools, and unsafe drinking water? Why don’t these people get to share in the same benefits of urbanization?

It might not be the most pleasant topic, but how cities disposed of their waste is as much a part of their history as the arts and technology they produced. Sanitation practices shaped our cities. The time people spent carrying buckets to cesspits was time they could not spend farming or tool making. The location of cesspits and the routes to—and around—them shaped street plans and patterns of urban life. The future of our cities might be shaped as much by what flows under them as what goes on above.

Sources:

Corbin, Alain. The Foul and the Fragrant: Odor and the French Social Imagination. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986.

Magness, Jodi. "What’s the Poop on Ancient Toilets and Toilet Habits?" Near Eastern Archaeology 75, no. 2 (2012): 80-87.

McMahon, Augusta. “Trash and Toilets in Mesopotamia: Sanitation and Early Urbanism.” Friends of ASOR, Volume IV, No. 4, April 2016.

McMahon, Augusta. "Early Urbanism in Northern Mesopotamia." Journal of Archaeological Research 28, no. 3 (2020): 289–337.

Milner, George R. "Early Agriculture’s Toll on Human Health." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - PNAS 116, no. 28 (2019): 13721–13723.

Reid, Donald. Paris Sewers and Sewermen: Realities and Representations. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Storey, Glenn, Rebecca Storey, Li Liu, Sarah M. Nelson, and Roger S. Bagnall. Urbanism in the Preindustrial World: Cross-Cultural Approaches. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2006.

Tajima, Kayo. “The Marketing of Urban Human Waste in the Early Modern Edo/Tokyo Metropolitan Area.” Urban Environment, 1 (2007): 13–30.

Worster, Donald. "The Good Muck: Toward an Excremental History of China." RCC Perspectives, no. 5 (2017): 1–54.

About the author: Bennett Sherry holds a PhD in history from the University of Pittsburgh and has undergraduate teaching experience in world history, human rights, and the Middle East. Bennett writes about refugees and international organizations in the twentieth century. He is one of the historians working on the OER Project courses.

Cover image: Communal latrines at the Beit Shean Archaeological Site, Israel. © Independent Picture Service/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments