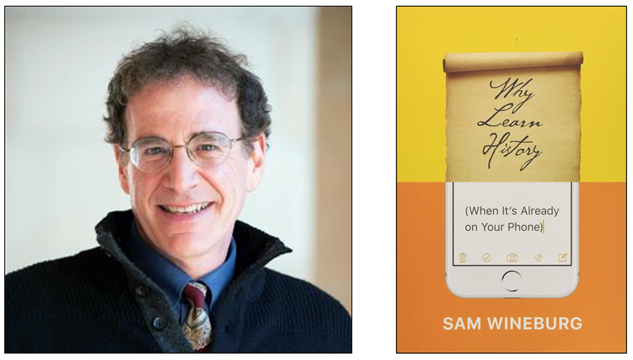

Drumroll please! We are thrilled to announce our summer OER Conference for Social Studies Book Club pick! This month you are invited to join us in reading Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone) by Sam Wineburg (IndieBound / Amazon), who happens to be one of our keynote speakers for the OER Conference for Social Studies.

Since the 1990s, Sam Wineburg has been one of the leaders in research on historical thinking and the teaching and learning of history. He is also one of the founders and directors of the Stanford History Education Group (sheg.stanford.edu), one of the largest providers of free educational resources in the world. Wineburg believes it is essential to provide students with the critical thinking tools necessary to sort through the incredible amount of information being thrown at them every day, and to do so may require updates to traditional teaching practices.

Our community discussion about Why Learn History will kick off with our first book club questions on July 14 right here in this thread, located in the OER Conference for Social Studies Discussion Forum. We’ll post a new question each Thursday for three weeks leading up to the conference which takes place August 3-4. So, grab a copy of the book, bookmark this thread so you can return on the 14th, and prepare for some rich discussions with other members of the community.

Our first week of conversations will cover Part One of the book. Let the reading begin!

Why Learn History // Week One Questions

We are excited to start our book club conversation on Why Learn History (When it’s Already on Your Phone) as we make our way to Sime Wineburg’s August 4th keynote address in the OER Conference for Social Studies. Post your thoughts and answers to the questions below or add your own question. Erik Christensen will be leading the discussion and will be checking in throughout the day to respond to the conversation.

In Chapter 1 "Crazy for History" Wineburg gives a critical analysis of American testing systems (and their effectiveness) and reaches the conclusion that "...no national test can allow students to show themselves to be historically literate." Further, Wineburg makes the claim that multiple choice tests "convey the dismal message that history is about collecting disconnected bits of knowledge..., where one test item has nothing to do with the next, and where if you can't answer a question in a few seconds, it's wise to move on to the next. [These] tests mock the very essence of problem solving."

- How should teachers of history in 2022 test our students?

- How do you determine if your students are learning history?

- How do you, to paraphrase Wilfred McClay, make those hard choices about what gets thrown out of the story so that the essentials can survive?

Why Learn History // Week Two Questions

Bloom's Taxonomy is referenced in many professional development sessions, teacher-admin conversations, and there may even be a poster of this pyramid in your classroom. Wineburg suggests that in a history classroom, Bloom's Taxonomy should be inverted so that knowledge is at the top.

- Do you agree with Wineburg's thesis - that Bloom's Taxonomy doesn't work in a history classroom?

- What would an inverted version of the pyramid look like in your practice?

- Is knowledge the result of critical thinking? Or is knowledge needed to think critically?

Why Learn History // Week Three Questions

In Chapter 7 "Why Google Can't Save Us" Wineburg dives deep into the internet's ability to deeply confuse expert and novice historians (and everyone else!). He describes several case studies that highlight how difficult it can be to assess information that we come across online.

- As more students are conducting research online, how are you managing the information they are exposed to?

- Do you teach digital literacy?

- How do you practice online reasoning or claim testing? How do you practice it with your students?

- What routines or activities have made the biggest impact to negotiating the power of the internet in your classroom?

Post your response to the questions in the comments below as we complete our final week of the Book Club. Be sure to join us for Sam Wineburg’s Keynote Address on August 4 at 1:00 PM PDT!