By Rachel Hansen, OER Project Teacher

Iowa, USA

Note: Over the new few months we'll be gradually bringing over some of your favorite articles from the old BHP Teacher Blog. Enjoy this throwback piece, originally posted October 18, 2018.

I love to write, but I haven’t always. When I left my small, rural high school for the opportunity of a big university education, I learned pretty quickly I was in over my head with the kind of argumentative writing my history courses demanded. I spent the better part of freshman year at the writing center learning how to write. I became a better writer, but it was a humbling process.

Now, I teach struggling readers and writers in their first year of high school. When they grumble about writing, I get it. I also know they’ll become better writers. They always do. Here’s how we do it:

1. Ignite their intellectual curiosity. Great writing begins with deep thinking. I like to entertain wild thinking and big questions. We have thinking partners in class, so students are always verbalizing what they’re learning ⎼ often using “I notice…” and “I wonder…” statements. Before we ever try to write about the driving question, we’ve talked about it ⎼ a lot. Walking debates and Socratic seminars are two of our favorite ways to think deeply about questions. I want students’ brains to be dripping with curiosity so they feel confidently ready to share what they’ve been thinking about when it’s time to write. If students feel like their brains are empty, you can bet their pens will be, too.

2. Establish strong writing routines. I don’t want the first time a student writes a claim to be when they pen it out on the Investigation essay. We make claims all the time. We write claims all the time. We test claims all the time. We write in class almost every day. Perfect practice makes perfect. Writing routines in class mirror those required to complete an argumentative essay: writing a claim, structuring paragraphs, citing textual evidence, and summarizing information. When the act of writing gets to be too much, sometimes, we just talk about writing. What does a thesis statement do? What does good essay organization look like? Which claim tester makes for the most valid argument?

3. Provide scaffolded frameworks of support. Keep the writing training wheels on until all the wobbles are worked out. For Investigation 1, we walk through the entire essay together. (I should clarify – our first essay is actually Investigation 0, which is a baseline assessment. There are no training wheels for anyone on that one, as I want to get a true sense of where students are when they first come to me!) Each student loses the training wheels at a different point in the class. Usually by Investigation 6 or 7, most students are ready to fly solo. The goal is for students to produce independent work by the end of the year.

4. Show students exemplary writing and ask them to emulate it. To produce better writing, students need to see good writing, study how it’s constructed, emulate it, and then compare their attempt to the gold standard. Rinse and repeat. We provide students with two samples of writing, one weak and one strong. We highlight claims, look to see if topic sentences reinforce the claim, and then highlight areas of strong argumentation. After grading the samples, students compare their own writing to the samples we just analyzed. Their goal is to make their writing as much like the strong sample as they can.

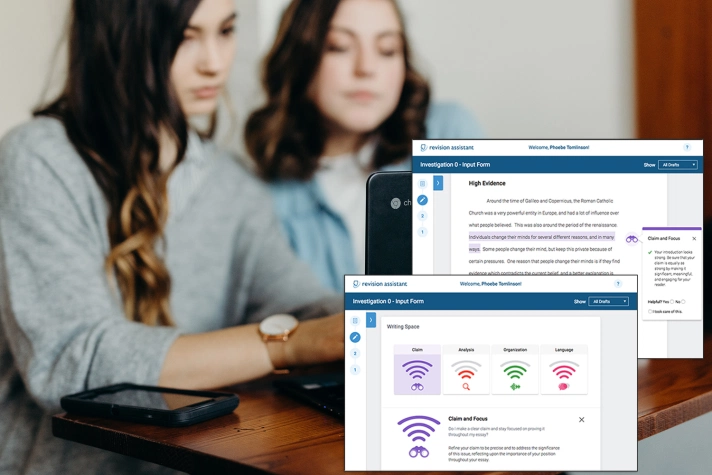

A snapshot of BHP’s free essay-scoring service, BHP Score

A snapshot of BHP’s free essay-scoring service, BHP Score

5. Give targeted and timely feedback. BHP Score makes targeted and timely feedback so easy. We treat the Signal Check like a teacher evaluation. Once students have it, we spend an entire class period breaking down that feedback. I’ll often start with a mini-lesson, and then break the room into pods focusing on different aspects of the essay where students struggled. It’s also been really beneficial to partner strong and weak writers together to talk about ways they approach the writing process. With feedback instantly at our fingertips, I spend the bulk of my time planning for re-instruction.

Every student can become a better writer. Spark their intellectual curiosity, build strong routines, and celebrate growth. Their English teachers will be singing your praises by the end of the year, and so will all the history teachers that come after you—especially those university professors who assign an argumentative essay on Day 1.

About the author: Rachel Hansen is a high school history and geography teacher in Muscatine, IA. Rachel teaches the BHP world history course over two 90-day semesters to about 50 ninth- through twelfth-grade students each school year.

Cover image: BHP students in the classroom at Aspire Alexander Twilight Secondary Academy, Sacramento, CA. Photo © Amanda Lipp.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,