By Trevor Getz, OER Project Team

San Francisco, USA

This is the first in a three-part series on the use of comics in the social studies classroom, focusing largely on Black creators and subjects, both in recognition of Black History Month and also to acknowledge the importance of celebrating diverse voices year-round. Originally published in February 2021, we think it makes for a great introduction to the genre. Click here for additional graphic history content, including lessons, graphic biographies galore, and more!

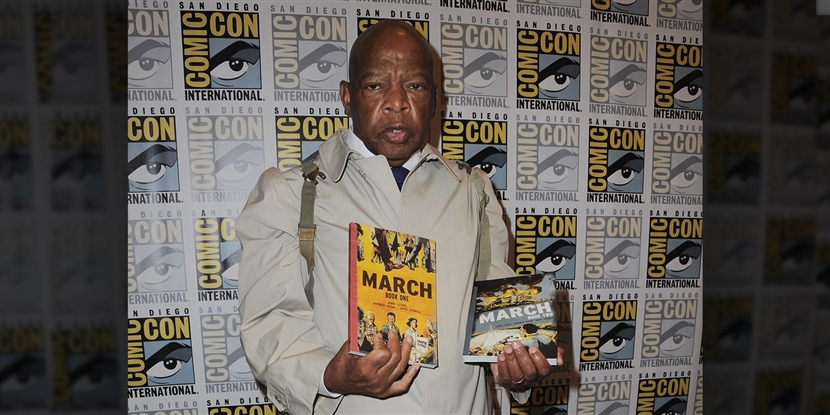

It was 2008 and Congressman John Lewis’s staff were in a long meeting. They were trying to figure out how to tell a story about Lewis’s life that would include the scale of the Civil Rights Movement. They considered all the traditional media—novel, documentary, podcast. Nothing seemed right. It was only when Andrew Aydin, Lewis’s aide, returned to his comics-filled home that a lightbulb came on. The next morning, Aydin proposed they produce a comic book or graphic novel. Congressman Lewis recalled a comic book from his youth—the famous 1957 Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story.[1] This comic helped inform, inspire, and recruit a generation of youth to fight for civil rights. It’s part of a history that Dr. Yohuru Williams describes in this compelling keynote talk during the 2020 OER Conference for Social Studies. Lewis gave the project the green light, and thus was born March, the best-selling nonfiction graphic novel of all time.[2]

Within a few years, Lewis was a star at the annual Comic-Con convention, appearing in cosplay as himself, donning a replica of the beige trench coat and backpack he wore in 1965 when participating in the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery as a 25-year-old civil rights activist.

John Lewis (third from left) walks with Dr Martin Luther King Jr and others as they begin the Selma to Montgomery civil rights march from Brown's Chapel Church in Selma, Alabama, US, 21st March 1965. © William Lovelace/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

John Lewis (third from left) walks with Dr Martin Luther King Jr and others as they begin the Selma to Montgomery civil rights march from Brown's Chapel Church in Selma, Alabama, US, 21st March 1965. © William Lovelace/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

As an author of history-focused comics myself, I have sought for years to articulate where the power of comics lies. The creators of both Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story and March recognized the unique qualities of comics as a form of media. Comics have the power to engage, to build affinity and empathy, and to express complex human stories in empowering ways. These qualities make comics potent tools for creating more inclusive histories and classrooms.

This blog is the first in a three-part series about graphic histories. In this post, I’m going to explore what I see as the unique qualities that comics bring to a history classroom. In subsequent posts, I’ll write about the path that led me to bring together my twin loves of learning and comics, and then finally how this combination led to the graphic biographies featured in the World History Project courses.

But I need to start by talking about why comics are such a potent medium. Their power lies in how comics combine two modes of communication—images and text. Most of us live our lives in a multimedia, visual environment. Yet we are generally told that serious work appears only in one medium—writing. This emphasis gives textbook writers and other intellectuals the power to construct the narratives that inhabit our classrooms. Unfortunately, this excludes most of the population from the crafting of history stories. Comics are a more democratic medium. Many of the finest comic creators, as I’ll describe below, are self-taught and come from the margins of society or under-represented groups. Many of them tell stories that are meaningful to them, stories that are often inhabited by the people they grew up with or those who look like them—and who also look a lot more like our students today!

While images and text work harmoniously in comics, images live in a strange part of our brain that triggers empathy much more easily than writing does. The images in comics allow creators to tie their readers to the people who inhabit their work. Add this together with the increasing diversity of those characters, and you have a powerful tool for teaching both empathy and inclusivity.

I imagine that some of the Black comics creators of the last century knew this. Some of these early twentieth-century creators made comic strips for the major Black newspapers that emerged from the 1920s to the 1940s in northern US cities, serving populations swelled by the Great Migration. Wilbert Holloway and Clarence Washington, for example, introduced “Sunny Boy Sam” in the Pittsburgh Courier while Jay Jackson led a team that authored “Bungleton Green” at the Chicago Defender. Mainly meant to entertain a Black population, these strips told funny—but relatable—stories of Black men and women in the big city, sometimes with a political twist. But I want to focus for a second on a different creator: Jackie Ormes.

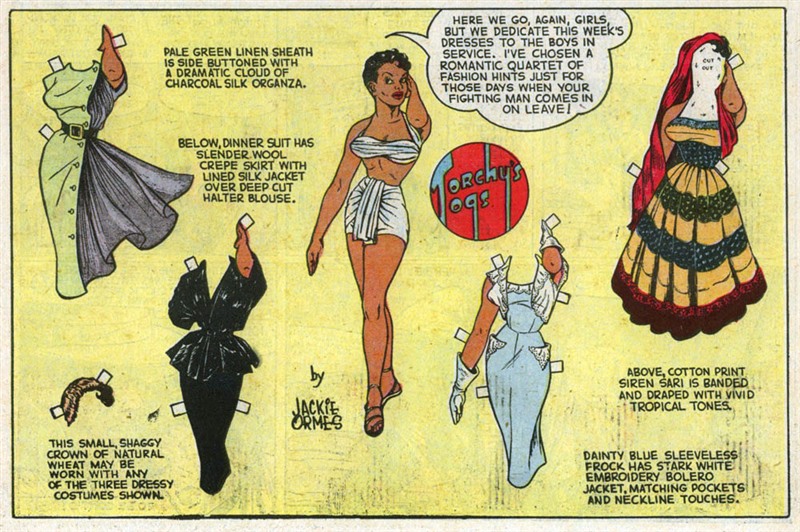

Torchy's Togs by Jackie Ormes, public domain.

Torchy's Togs by Jackie Ormes, public domain.

Often called the first Black woman cartoonist, Ormes’s most famous character is Torchy Brown. Created in 1937 for a strip called “Dixie to Harlem,” Torchy’s story reflects all the opportunity and danger of the Great Migration. After growing up poor on a Mississippi farm, Torchy heads north, encountering both sexual harrassement and racist challenges—first on the train, and then as she seeks a place to live. Torchy’s first comic-strip appearance was short, but she returned in 1950, this time pitched to a middle-class Black audience, in “Torchy in Heartbeats.” Across approximately 200 strips, Torchy lived a life full of music and fashion. Torchy comic strips even came with stylish cutouts that depicted the heroine and her fashionable professional clothes. But she also encountered discrimination: One notable sequence, which focused on pollution from a chemical plant that was sickening her community, was based on very real cases of environmental racism in the 1950s. Reading “Torchy in Heartbeats” today, one has to wonder which was more valuable to a young, female, Black reader: reading about problems like those they themselves experienced, or witnessing a successful woman who looked like them and whom they could aspire to emulate.

In Jackie Ormes’s time, there were few nonfiction comics, and most creators used fiction to tell stories that featured Black characters (or superheroes) and were aimed at a Black audience. This situation reflected the general American view that comics were, at best, entertainment and, at worst, subversive. But then, in 1992, Art Spiegelman won a special citation Pulitzer Prize for Maus, his graphic memoir of intergenerational trauma and the Holocaust. This recognition opened the door to nonfiction comics, many from Black creators.

|

Some notable works by and about Black comics creators:

|

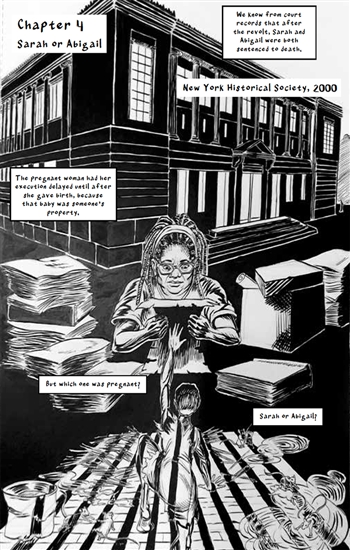

A powerful panel from Wake, © and courtesy of Rebecca Hall.

A powerful panel from Wake, © and courtesy of Rebecca Hall.

I want to conclude by talking a little bit about one of these recent graphic histories, Rebecca Hall’s Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts.[3] I recently spoke to Hall—a descendant of enslaved people herself—about this work, forthcoming in June 2021. Hall told me that she was inspired to create this graphic history from her memories of reading Maus as a young adult, much as Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story had inspired John Lewis. The book began as a PhD dissertation, but Hall knew she didn’t want the history she uncovered to be exclusively read by other academics. Instead, the former high school teacher created a book that might help address classroom problems of inclusivity and history. “I particularly wrote this book for African-Americans, who had been denied this history, but it’s also for anyone who thinks it’s time to come to terms with America’s history of slavery,” Hall told me. This is also a graphic text that is intended to help set the historical record straight. “The argument I’m making—that women planned and participated in slave revolts—is controversial,” she said. “But when you look at the historical sources of slave revolts, there are women all over them.” Finally, Hall created a work that she herself finds liberating. “It has become a memoir of my time in the archive, and of being the descendant of slaves, and living in the afterlife of slavery. I couldn’t tell this story in a regular book.”

From Jackie Ormes to Rebecca Hall and John Lewis, Black comics creators have played an important role in the fight for liberation, equity, and social justice. It’s time we gave their work the respect it deserves.

Looking for more? Join us in the OER Project Community today! And if you aren’t registered with us yet, create an account here for free access to the OER Project Community and more.

[1] You can read the full comic here: https://www.crmvet.org/docs/ms_for_comic.pdf

[2] John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell, March, Volumes 1–3, Top Shelf Productions, 2013–2016.

[3] Rebecca Hall and Hugo Martínez, Wake: The Hidden History of Women-led Slave Revolts, Simon and Schuster, 2021.

About the author: Trevor Getz is Professor of African History at San Francisco State University. He has written eleven books on African and world history, including Abina and the Important Men. He is also the author of A Primer for Teaching African History, which explores questions about how we should teach the history of Africa in high school and university classes.

Cover image: Rep. John Lewis attends the Warner Bros. presentation during Comic-Con International 2015 at the San Diego Convention Center on July 11, 2015 in San Diego, California. © Albert L. Ortega/Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments