Trevor R. Getz, WHP Team

San Francisco, USA

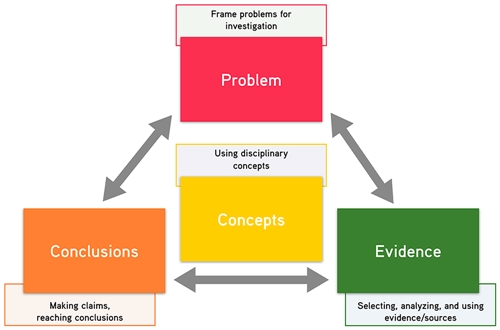

It took me a long time and a lot of hard work to figure out how to think like a historian, but it’s been worth it. I use those skills every day, to orient myself to the world around me, to figure out what’s going on, and to make plans for the future. Probably the most important historian’s practice I’ve learned is the skill of conducting historical inquiry.

At its core, historical inquiry is a pretty simple process. First, the historian identifies a problem to investigate. These problems can come from anywhere – my MA thesis topic came from stories my grandfather told me. My dissertation was based on an idea my advisor randomly shared with me.

I have been working for 13 years on a question that the gardener at the National Archives of Ghana asked me one afternoon when we were both trying to cool down in the shade of a giant tree. (The question: What happened to the Fante Confederation in West Africa? It’s an obscure question to you, but it was important to him. Look it up!). Sometimes the sources guide you to a problem. Sometimes you identify something in the contemporary world and want to find its origins. What historical problems have in common is that they are all questions about the past and its meaning. That’s it.

Equipped with a question, a historian has to figure out a pathway to getting to an answer. The obvious thing to do is to go get as much evidence as possible—right away—but that’s rarely the next step. Instead, historians normally make conjectures. We develop proposals, really based on what we already know. This is what I did when I started studying the Fante Confederation, a constitutional state that appeared in West Africa for about four years in the nineteenth century, and then disappeared. My theory was that it didn’t succeed because it didn’t have popular support.

Once we have a conjecture we set out to test our proposal, and that’s when we really start gathering the evidence. We already know where most of that evidence comes from – the secondary sources written by other scholars and the primary sources we find in archives. But these days, historians have a wide range of evidence to work with: not only written letters, documents, and reports, but also photographs, oral tradition, first-hand interviews, language, material remains, and much more.

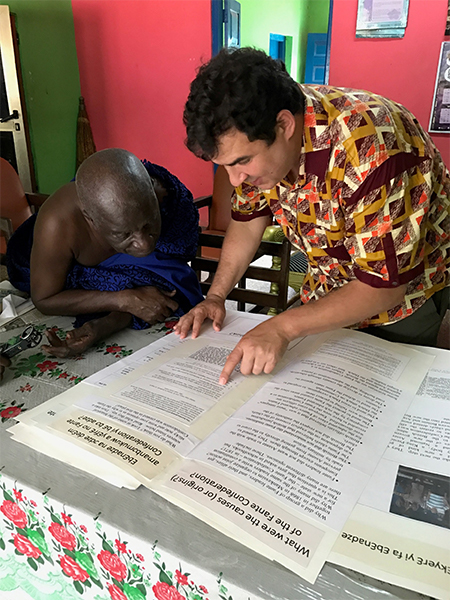

Trevor discusses the Fante Confederation with Nana Baa, ruler of Saltpond. Ghana. Image courtesy and © Trevor Getz.

The difficult thing about this wide range of sources is that each kind requires its own methodology. So, once a historian knows the type of sources in play, the next step is to study up on the methods needed to analyze them. Method usually refers to a way of doing things – the moves a historian makes to pull meaning from each piece of evidence. Method is closely related to the skills that we know as historical thinking: testing claims, sourcing, contextualization, causation, continuity and change over time, and corroboration. When I went to assess my claims about the Fante Confederation, for example, most of the written sources I had were from the state’s leaders or the British, not from popular sources that could tell me how common people felt about it. So I began to work with the methods of oral tradition – collecting and interpreting narratives from people who were community historians within the Fante towns and cities.

An historian also studies up on the theories needed to analyze the evidence. Although theory and method are closely related, theory is generally a set of ideas that give the historian insight into filtering that evidence to get to an answer to a problem. So, for example, in thinking about the Fante Confederation, I studied all of the theory I could find about why people do or don’t support governments. I particularly studied the theoretical work about nationalism and the development of shared identities in countries around the world at just about the time the Fante Confederation was developing.

Now that all the evidence is assembled, the historian can use it to see whether the evidence supports their original conjecture. Maybe it does, or maybe the inquiry process has brought a better explanation to light, or maybe it’s time to start again and rethink those original suppositions. It is only when the historian has an argument that seems to be meaningful, that seems the best fit for the evidence, and that answers the problem, then it is time to take the next step, which is to make those conclusions public in some way. This might mean publishing a book or an article, but these days it might equally mean a blog post, a documentary film, or some other publishing medium. Unfortunately for me, the evidence I uncovered did not support my conjecture. Nor has it helped me to develop an alternative...yet. As a result, I still haven’t published this work.

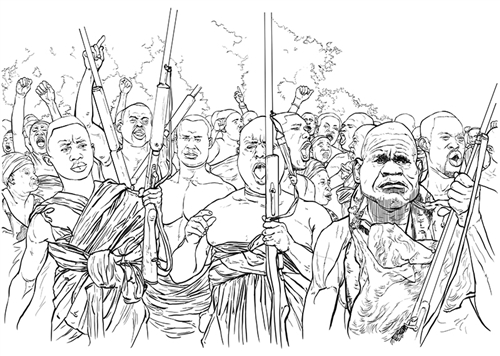

Fante men rallying for the Confederation, 1868–1871. Drawing by Bright Ackwerh. Image courtesy and © Trevor Getz.

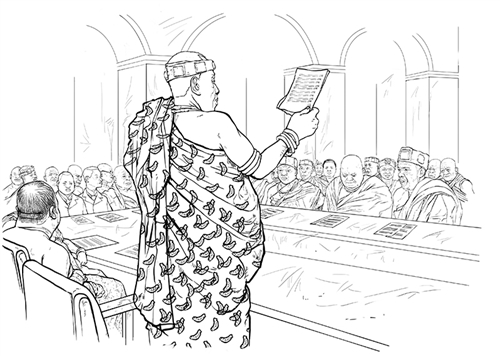

Meeting of the leadership of the Fante Confederation. Drawing by Bright Ackwerh. Image courtesy and © Trevor Getz.

Meeting of the leadership of the Fante Confederation. Drawing by Bright Ackwerh. Image courtesy and © Trevor Getz.

Fante confederation leaders meet with British officials. Drawing by Bright Ackwerh. Image courtesy and © Trevor Getz.

Fante confederation leaders meet with British officials. Drawing by Bright Ackwerh. Image courtesy and © Trevor Getz.

All of the steps above falls under the label of historical inquiry because they start with the historian asking a question and they end (usually! hopefully!) with the publication of some response to that question. Of course, historical inquiry is actually quite greedy, because it gobbles up all of the historical skills within itself. That is, when conducting inquiry, the historian sources, contextualizes, and produce accounts to answer causation questions, or continuity and change questions, or to contextualize phenomena, processes, or events.

So, to my mind, historical inquiry is kind of the pinnacle of a skills progression. It represents the height of the competency that we want students to take away from the OER World History Project or Big History Project courses. And you know what? It’s really satisfying as well. And fun. Inquiry is fun. I love it.

Practices of WHP Students

Practices of WHP Students

About the author: Trevor Getz is a professor of African and world history at San Francisco State University. He has been the author or editor of 11 books, including the award-winning graphic history Abina and the Important Men, and has coproduced several prize-winning documentaries. Trevor is also the author of A Primer for Teaching African History, which explores questions about how we should teach the history of Africa in high school and university classes.

Cover image: OER World History Board Member Tony Yeboah interviews gyaasehene Kobina Amonu of Abakrampa, Ghana about the Fante Confederation. Image courtesy and © Trevor Getz.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments