By Trevor Getz, OER Project Team

San Francisco, USA

We’re publishing this blog as part of an exciting announcement: a fully remodeled Climate Project is coming your way this April! We’re previewing the launch with a sneak peek at some of our new materials and resources. Head over here to check them out!

It may be no surprise that students have a wide variety of attitudes and emotions when it comes to climate change. Some are deeply concerned about the future. Some are optimistic about what can be done to confront climate change. Still others are skeptics about the whole thing. Often these attitudes are influenced by outside factors like parents and family, news and social media. When students have the opportunity to learn more about climate change, they start to connect to the issue at a personal level.

The students in our classrooms today are central to envisioning and making the future, but they can’t do it if they’re paralyzed by fear and depressed about the future. That’s why we have built Climate Project around climate optimism—hope is key. This generation of students must have hope if they’re going to want to learn what’s needed to strategize, innovate, create policy, and lead the smart, clean, economically-powerful green future we need.

When students work optimistically on strategies for reducing and mitigating climate change, they see themselves in the innovations and practices that are possible. They identify interesting careers for themselves as urban planners, engineers, or teachers. Finally, they begin to engage in community thinking. They hear how their classmates may be developing their own connections to different climate change careers or strategies. Together, they piece together the puzzle of policy, financing, and social change we’re going to need to get these innovations off the ground. They leave the class excited—not necessarily in agreement about everything, but with a sense that there is work to do, and they can help do it.

Adam Esrig teaching Climate Project in his New York classroom. Hear Adam speak about encouraging climate optimism in his classroom at Fundamentals: OER Project Conference for Social Studies on March 23. Learn more and register here. Photo courtesy of Adam Esrig, credit Ryan Serrano.

This feeling of excitement is crucial because it challenges the perspective of climate doom. Doomerism is the belief that there’s nothing we can do; it’s too late to mitigate the worst effects of climate change. And lots of young people experience doomerism. A 2022 study found that “as many 59% of youth and young adults said they were very or extremely worried about climate change and more than 45% said their feelings about climate change negatively affected their daily life and functioning.”[1] These sentiments leave little room or motivation to work on the challenges of climate change.

Climate optimists, by contrast, understand the challenges but believe there is still something we can do to make our world and our shared future better. This isn’t blind optimism. It isn’t the belief that everything is going to be OK and we can just relax about the whole climate change thing. Instead, it’s urgent optimism, which, researcher Hannah Ritchie tells us, “isn’t about looking away from the climate crisis that faces us,” but rather “facing up to it, not from a place of ‘damage limitation’ but with a clear vision of the future we can build.”[2]

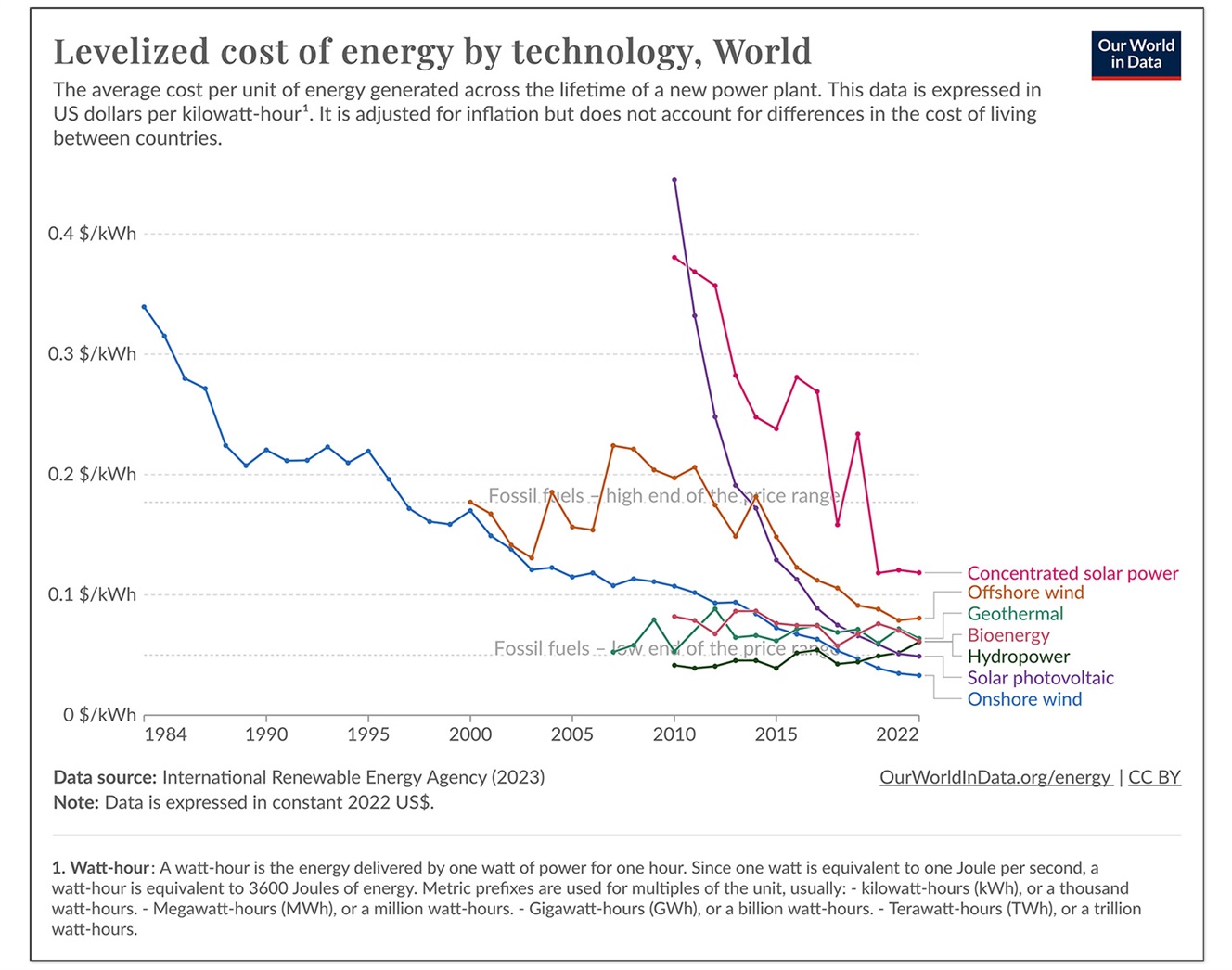

The average cost per unit of energy generated across the lifetime of a new power plant. Graph by Our World in Data, CC-BY.

Of course, there’s another reason why Climate Project is built on a foundation of optimism. There’s plenty of evidence that we’re right to be hopeful. The world has seen significant advances in green technology such as renewable energy, battery storage, and precision farming. Public awareness and activism are on the upswing globally. Lots of communities have committed to adaptation and building resilience. The financial sector is more engaged in investing in green technologies than ever. Yes, there are still challenges—lots of technologies temporarily stall or face deep obstacles to implementation. If we look past the noise, though, we can see that we still have a chance to mitigate the worst impacts of climate change. But only if we are hopeful enough to give it a try!

Interested in building climate optimism among your students? The new Climate Project is a customizable course focused on building student understanding and optimism about their role in addressing the climate crisis. It aims to foster a range of skills including research, claim testing, digital literacy, and writing—skills that are not only essential to the discussion of climate change but can be carried by students to other subjects and their broader lives. Learn more about the fully updated course here.

[1] Caroline Hickman et al, “Climate Anxiety in Children and Young People and Their Beliefs About Government Responses to Climate Change: A Global Survey,” The Lancet, December 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3.

[2] Hannah Ritchie, Not the End of the World (New York: Little, Brown Spark, 2024). Excerpted in Time, Jan 5, 2024 https://time.com/6552329/urgent-optimism-climate-action-essay/.

About the author: Trevor Getz is Professor of African History at San Francisco State University. He has written eleven books on African and world history, including Abina and the Important Men. He is also the author of A Primer for Teaching African History, which explores questions about how we should teach the history of Africa in high school and university classes.

Cover image: Digital circular chart made of stone and grass showing different segments of alternative energy and nature. © Andriy Onufriyenko / Moment / Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,