Bennett Sherry, WHP Team

Maine, USA

Pandemics are scary. People don't act like themselves when they're scared. Think about some of the things you or your family and friends have done during the current pandemic. Maybe you noticed that a dear family friend now guards a dragon's hoard of toilet paper. Individuals act in odd ways when they’re scared. And when fear is strong enough, like during a pandemic, it can make whole groups of people change their behavior. Sometimes this change is for the worse. Sometimes, though, crises can pull us together, bringing out the best, rather than the worst of humanity.

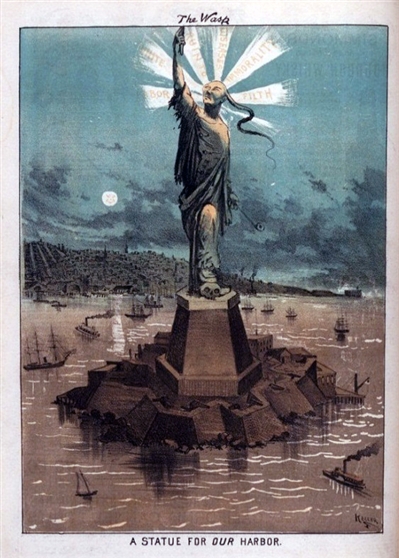

Many of the worst reactions to pandemics are rooted in a lack of information. For most of our history, humans did not understand what caused disease. So they often blamed each other. During a fourteenth-century outbreak of bubonic plague (known as the Black Death), many Europeans believed that Jews were poisoning public wells. These false accusations led to the persecution and murder of entire Jewish communities. During another outbreak of bubonic plague in the nineteenth century, the British officials governing South Africa forcibly segregated the black population from white settlers, setting a precedent for the official apartheid policies of the twentieth century. In the second half of the nineteenth century, public sentiment turned against Chinese immigrants, and they were repeatedly blamed for outbreaks of disease on the West Coast. This scapegoating contributed to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which placed heavy restrictions on Chinese immigration to the US. In 1881, the cartoonist George F. Keller published the image below in The San Francisco Illustrated Wasp.

In a parody of the Statue of Liberty, a caricatured statue of a Chinese man stands in San Francisco’s harbor, with the words “filth” and “disease” surrounding his head. Public domain.

In a parody of the Statue of Liberty, a caricatured statue of a Chinese man stands in San Francisco’s harbor, with the words “filth” and “disease” surrounding his head. Public domain.

Scapegoating isn’t always about religion, ethnicity, or race. When cholera outbreaks ravaged nineteenth-century Europe, many in the working class believed conspiracy theories that the ruling classes were poisoning the poor. In response, mobs of people attacked doctors outside cholera hospitals. The middle and upper classes, meanwhile, blamed cholera on the “dangerous classes”—the working poor. In each of the cases above, a lack of information generated violence or prejudice against a group of people.

Inaccurate information can have disastrous consequences. When politicians or public health officials fail to provide information, it confuses people and enables disease to spread more easily. When the first cases of the Spanish flu appeared in 1918, the world was at war. Most countries fighting in the war censored their newspapers. But keeping people uninformed only created more fear. The Red Cross reported that some sick families in America starved to death because volunteers and community members were too terrified to deliver food to them. Victor Vaughan, a US Army surgeon, warned that social panic about the disease—not the disease itself—was on the verge of wiping out civilization “within a few more weeks.” When leaders fail to inform the public, individuals act in dangerous ways—hoarding supplies, neglecting neighbors, and looking for people to blame and persecute.

When people are informed, they’re better able to make rational decisions. John M. Barry, author of The Great Influenza, writes that when public officials chose to tell the truth about the Spanish flu, outcomes improved. The mayor of San Francisco promoted measures to combat the disease. “Where people had accurate information and knew what they faced,” says Barry, “they often performed heroically.” San Francisco was devastated by the flu. But its rates of infection and death during the second wave of the outbreak were lower compared to other major American cities. Society in San Francisco continued to function. People received the food they needed. Nurses, doctors, and police officers—informed and aware—risked their lives to provide necessary services to their community.

During the Spanish flu pandemic, Seattle street cars required passengers to wear masks. The Seattle Chapter of the Red Cross produced 260,000 masks in three days. Public domain.

During the Spanish flu pandemic, Seattle street cars required passengers to wear masks. The Seattle Chapter of the Red Cross produced 260,000 masks in three days. Public domain.

These are scary times. Don’t obsess over the news. But do read it. The truth is one of the best weapons against pandemics. And there’s plenty of good news out there. The world-class chef José Andrés has donated thousands of medical masks to hospitals and transformed his restaurants into community kitchens, dedicated to feeding those who need it. There are countless stories like this: stories of compassion and communities coming together. Every day, doctors, nurses, and healthcare workers are putting themselves at risk to care for strangers. In times like these, it’s critical to remember that disease doesn’t care what language you speak or what country is on the cover of your passport. As individuals, neighborhoods, and nations, we must work together, because we are only as safe as the most vulnerable in our community.

Chef José Andres' converted all his Washington restaurants (Jaleo shown here) into 'community kitchens' in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. © Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.

Chef José Andres' converted all his Washington restaurants (Jaleo shown here) into 'community kitchens' in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. © Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.

Sources

Aberth, John. Plagues in World History. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2011.

Barry, John M. The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History. New York: Viking, 2004.

Barry, John M. "Pandemics: Avoiding the Mistakes of 1918." Nature 459, no. 7245 (2009): 324-325.

Poos, Lawrence R. “Lessons from Past Pandemics: Disinformation, Scapegoating, and Social Distancing.” Brookings Institution: Techtank. March 16, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2020/03/16/lessons-from-past-pandemics-disinformation-scapegoating-and-social-distancing/

Snowden, Frank M. Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019.

Spinney, Laura. Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World. New York: Public Affairs, 2017.

About the author: Bennett Sherry holds a PhD in history from the University of Pittsburgh and has undergraduate teaching experience in world history, human rights, and the Middle East at the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Maine at Augusta. Additionally, he is a research associate at Pitt's World History Center. Bennett writes about refugees and international organizations in the twentieth century.

Cover image: A nurse hands a policeman a balloon as a symbol of hope while doctors, nurses and hospital workers applaud outside at Puerta de Hierro hospital on March 29, 2020 in Madrid, Spain. © Denis Doyle / Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,