By Molly Sinnott

When you’re looking for a new coffee maker, you look to see what other consumers have said about the product, right? Is it intuitive to use? Is it built to last? And perhaps most importantly, does it make good coffee? So why wouldn’t you do the same thing about new material you’re thinking about teaching?

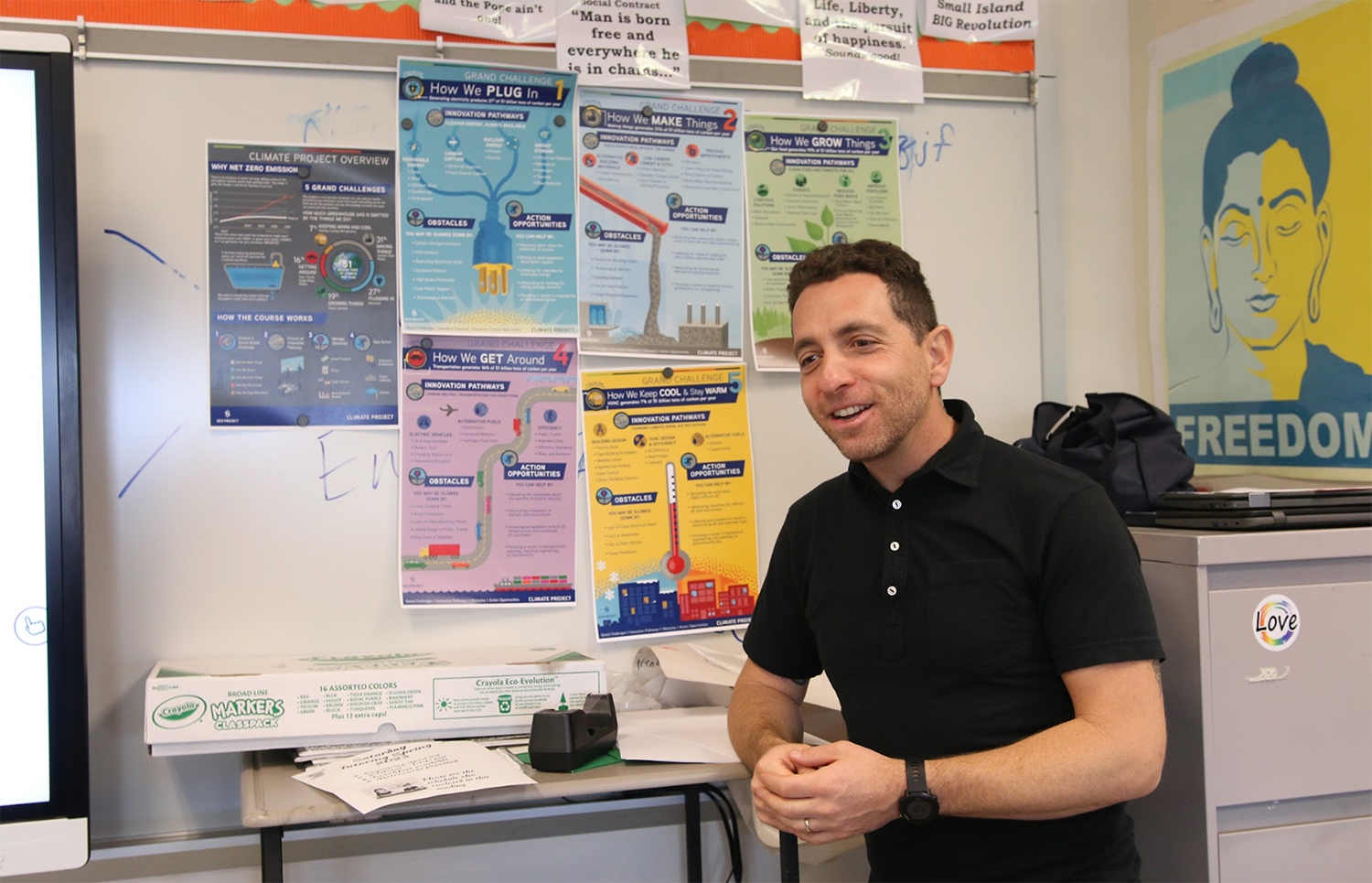

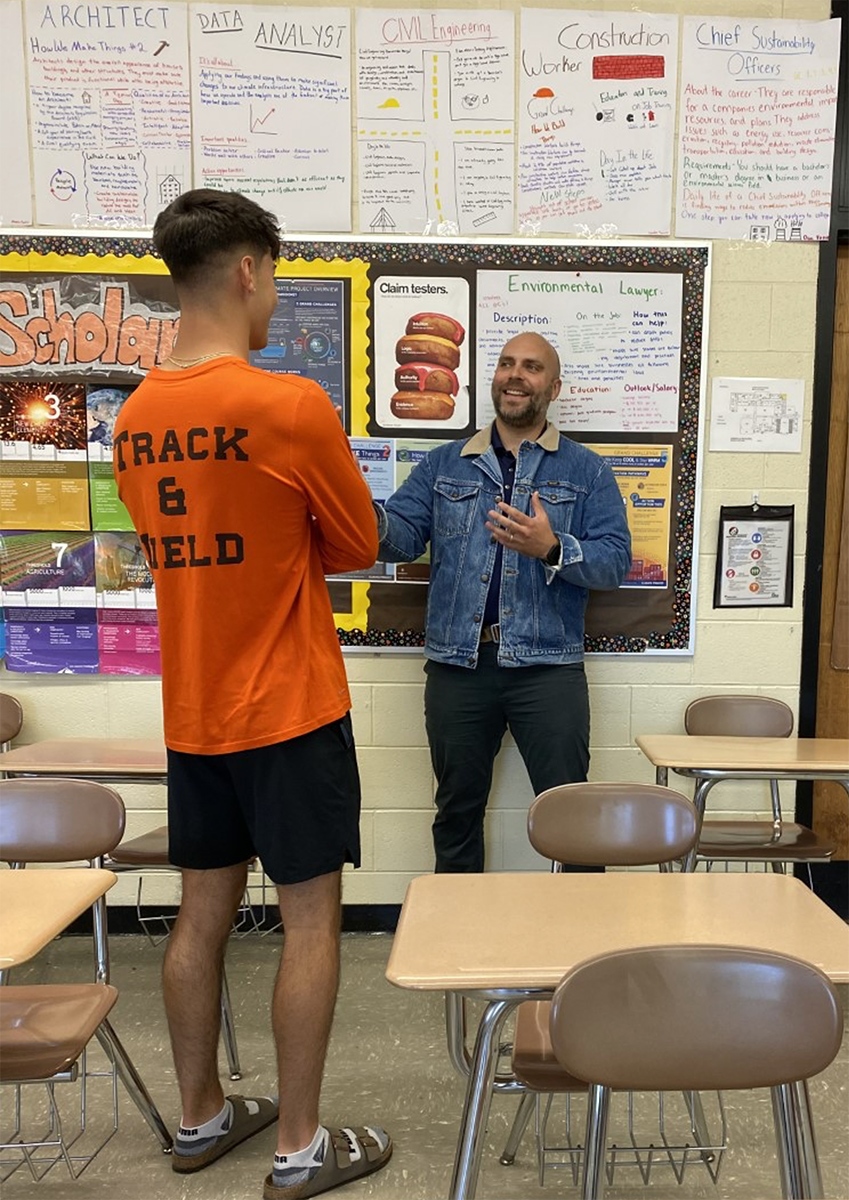

Teaching climate change is new to many people, so we thought it might be helpful if we asked some experienced educators who have done it to share their thoughts. Adam Esrig and Mike Skomba are both seasoned OER Project teachers who recently taught Climate Project as well. Here they provide insight from their own experiences for other teachers who are interested in seeing how Climate Project might fit in their classrooms.

Adam and Mike teach high-school juniors and seniors in New York and New Jersey, respectively. Teaching climate change was a new endeavor for both. They’ve shared five key takeaways from their experiences:

First, teaching climate change doesn’t require you to be a science expert. For Adam, there was some uncharted territory in the form of some technical concepts. As a history teacher, he says, “I have a bunch of different ways to explain the concept of nationalism. But trying to explain why rotting food releases methane? I don’t have a nifty way of breaking that down yet.” But this lack of expertise in the science wasn’t really a problem: “It’s really about engaging students to become the sense-makers in the course. The students have the power to do the research, become experts on something, and present those ideas to others.” Mike makes the connection to other social studies courses he’s taught: “You don’t have to be an expert in all 30 disciplines that Big History interacts with, right? It's about being a lead learner, but this is also mostly familiar stuff. Climate Project deals with social studies topics like civics, culture, economics, and geography.”

Adam Esrig teaching Climate Project. Photo courtesy and © of Ryan Serrano.

Next, students are genuinely interested in the human impact of climate change. Adam says, “My students really connected with the topic of adaptation and human health. It was powerful because they could explore the human side of things, which students found really compelling. Like with the other social studies courses I’ve taught, we’re unraveling the human story here. And in this course, there’s a self-reflection piece that helps students think about their own biases, culture, and how that connects to their own community.” Mike adds, “My students wanted to talk about climate justice and political activism. In the future, I plan to create some more space for that, to have debates and let students feel like their voices are being heard.”

An image from Are Natural Disasters Actually Natural?: Crash Course Climate & Energy #9 video.

Adam and Mike also tell us that students understand the importance of climate change, but they need support to perceive what they can do about it. “My students took to the ideas. It didn’t feel hard to convince them that this information was worth understanding,” says Adam. “But initially there was a sense of disempowerment. There was a lot of, ‘The world’s coming to an end and there’s nothing I can do about it.’ I needed to scaffold and really break down the idea of community to help students see that it can mean more than one thing—it can be your family, your neighborhood, your school. Helping students grasp that concept allowed them to see action opportunities less abstractly and to think about what would work in different parts of their lives.”

In both classrooms, engagement thrives when students take the lead. Mike says that in his classroom, student leadership is a powerful force: “If you give them leadership opportunities, give them the right resources, and are flexible and supportive, they’re going to be engaged and have fun with it.” Adam agrees. “Put students in the driver’s seat,” he says. “I give them the tools and the overarching framework, but then students get to choose what to research and how a given solution might meet the needs of their community. Empower students not just to make sense of the information, but to take that knowledge and become advocates—the best part of the course was watching students create presentations and educate their peers.”

Mike Skomba and a student in front of student work on climate-related careers. Photo courtesy and © Mike Skomba.

Finally, linking careers to climate change helps students see the relevance to their own lives. In Mike’s class, they held a career fair to showcase how their existing interests and passions could align with a career working to combat climate change. Plus, he adds, “students put more effort into their projects when they saw that it could be repurposed for other things, that they might be able to use this for a résumé or internship down the line.” Adam says exploring career pathways worked in his classroom as well: “Coming out of the pandemic, it’s a great opportunity for students to reignite their interest in careers after high school. I have eleventh- and twelfth-graders in this class, and this is a unique way to get them started thinking about this.”

Check out the Climate Project Community for more firsthand accounts from teachers who have taught the course. If you’re teaching Climate Project in your class, we would love to hear from you!

About the author: Molly Sinnott is a member of the Climate Project editorial team. She was previously a classroom reading and writing teacher, specializing in supporting students to grow executive function skills. She focuses on building approachable and inclusive content for a diverse range of students.

Cover image: A variation on the Climate Project 5 Grand Challenges infographic, by OER Project, CC BY 4.0. Background photo by Artur Łuczka on Unsplash, CC0.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments