By Rachel Phillips

Senior Measurement & Learning Lead, OER Project

Introduction

Narratives are the heart of history. They are critical for history education because stories are one of the most powerful ways people learn. Stories build connections between people and ideas. They help us understand culture, community, and values. Good stories do even more than that. They can be interpreted in multiple ways, they help you build a rich picture in your mind, and perhaps most important, they can draw a learner into a new and exciting space, engaging them in topics they knew nothing about.

There are a lot of ways to tell and take in good stories. Picture books, oral retelling, novels, movies, TED Talks—the list of storytelling media goes on and on. In history, written text tends to be the most familiar genre, although it isn’t the only one: Movies (documentaries as well as fictionalized film versions) and art also dominate in this space because they can be highly engaging, showing context and conveying meaning. And now there is emerging genre that functions in a similar yet distinct way—graphic histories.

Graphic histories, sometimes called historical comics, are something that OER Project has come to value—and we’re in good company. We’ve talked to artists and authors in the field about why they believe graphic histories are such a rich and worthwhile genre. Stephane Manuel, founder and CEO of TrueFiktion, talks about designing for respect. Tessa Hulls, author of Feeding Ghosts, discusses how historical comics bring the macro- and microstories of history together. Argha Manna shares his love of how historical comics spark curiosity and provide a more democratic medium for taking in and expressing complicated information.

OER Project

Narratives allow us to see the relationships between events and their actors, rather than seeing those events and actors as disconnected “stuff” that happened in the past. In developing course materials, we generally deal with two main types of historical narratives—individual and national.[1] Individual narratives (micronarratives) focus on the personal lives of historical figures, and some scholars assert that they help humanize history.[2] Most often, these are compelling people we’ve heard a lot about: Christopher Columbus, Hitler, Gandhi, Rosa Parks, Socrates...the list goes on.

National narratives (macronarratives) usually represent the dominant culture and often give a limited and biased point of view. One such example is the narrative of the United States that points to progress and liberty as two of the key elements of American history. This limited narrative is only reflective of some people’s experiences, and certainly not of those who have been traditionally marginalized throughout our nation’s history. So how can we create a more comprehensive historical narrative?

One way we do this is through graphic biographies. The lives of everyday individuals are often lost in traditional history, and we want to restore the connection between the sensationalized or accepted narratives and the entirety of history. These graphic histories enrich and add depth to the historical record, showing us how a wide variety of people, most of whom have been traditionally overlooked, experienced the same event. Students experience more growth, both academic and personal, when we elevate personal and untold stories of people from all walks of life, providing a balance to the dominant narrative.

We also love graphic histories because they use art to convey a message and provide a window into the culture or time of the individuals being highlighted. This is not something that can be done through words alone. For students—and some adults—it’s challenging to imagine a period long-since passed, yet this is what they are required to do in their classrooms daily. The visual nature of historical comics provides students with context that is often difficult to glean from more traditional texts. Furthermore, they provide an opportunity to engage students who may struggle to connect with blocks of text on a page or the subject matter in its entirety by addressing it from different angles. By “seeing” history, students can empathize with many of the “common” men and women they are learning about. Graphic histories can also provide a mirror that allows students to see themselves reflected in the curriculum.

Detail from Islam Alhashel graphic biography, by OER Project, CC BY 4.0

Detail from Islam Alhashel graphic biography, by OER Project, CC BY 4.0

These are not the only reasons people make and engage with graphic histories. Here are some amazing examples of other ways graphic histories are being created and used.

Stephane Manuel

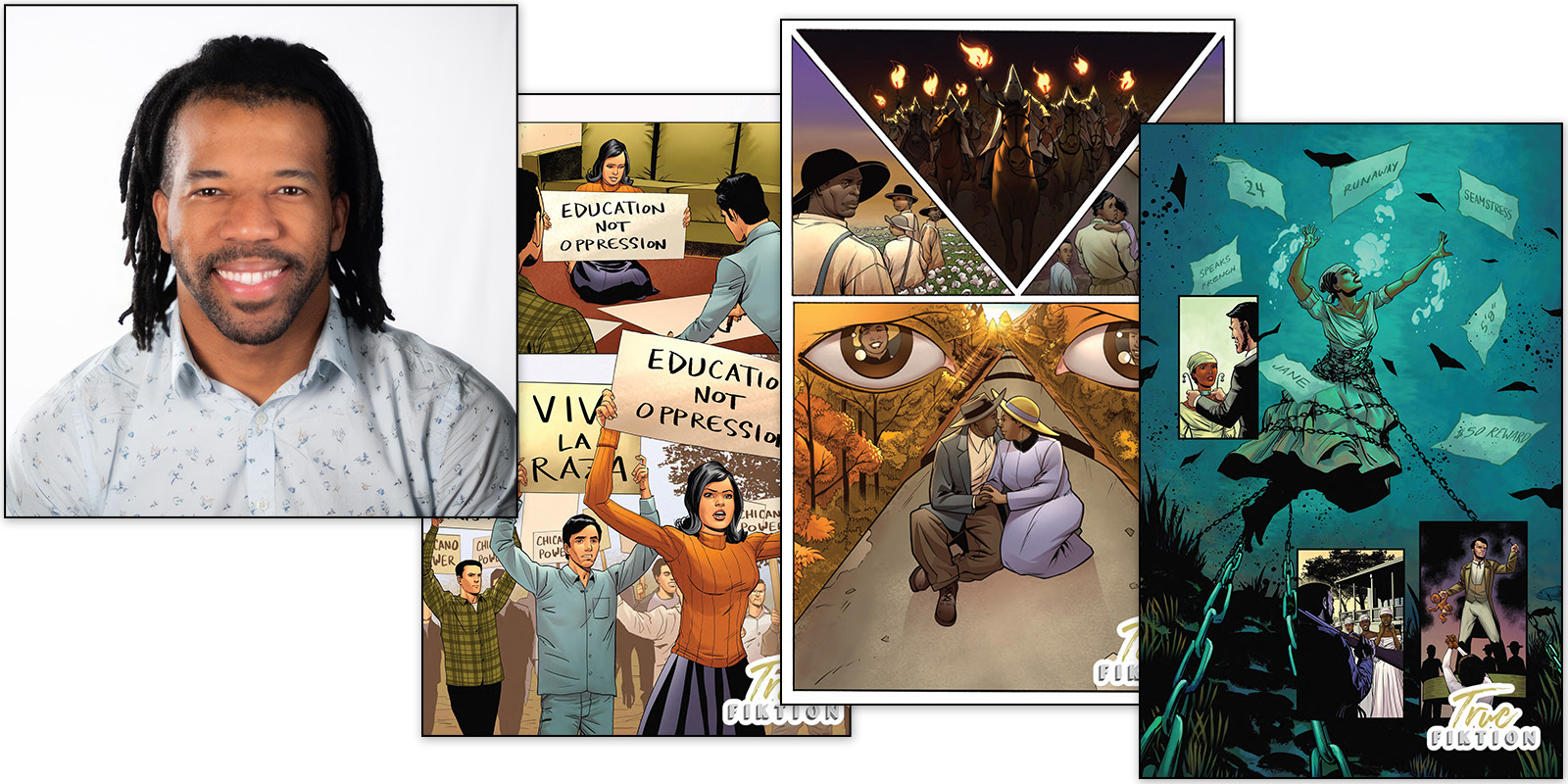

Steph Manuel, the founder of TrueFiktion, wanted to create an edtech startup based on historical comics. As a Black West Point graduate, he had the privilege of great education and multiple opportunities to serve countries overseas, but reflects that one thing his education didn’t do is help him understand the social issues that were happening in his community. As a result, he always felt like he didn’t have agency to improve his community because he wasn’t equipped with the right knowledge or mental models. Serving as an Army Officer, Steph faced the reality that he was fighting for freedoms that weren’t his own. The idea of freedom felt fictional in many ways, as it was something he had studied in school, yet it wasn’t a through line in all parts of history and in his lived experience. TrueFiktion became a way for Steph to provide a more accurate and inclusive picture of the past, one that students could relate to. He has said, “Regardless of how you identify you should be able to see yourself meaningfully represented in your history education.”

Stephane Manuel (left) and a selection of pages from The Great Migration. Courtesy and © the artist.

Stephane Manuel (left) and a selection of pages from The Great Migration. Courtesy and © the artist.

Steph’s approach to creating comics focuses on historically marginalized groups and presenting untold stories that offer differing perspectives. TrueFiktion highlights comics as a powerful tool in education, emphasizing the need for context, representation, and respect in the way history and social issues are taught to students. While one major goal for classroom use is for students to see themselves meaningfully represented, this is not Steph’s chief goal. As he’s stated, “Representation is a natural outcome of what we do; we design for respect.” It is also a way to get students to love themselves and their identities as part of history and to show examples of traditionally marginalized groups having agency and history. This is done by emphasizing the gaps. In other words, True Fiktion surfaces stories that highlight the resilience of people throughout history and are relevant to current social issues.

Tessa Hulls

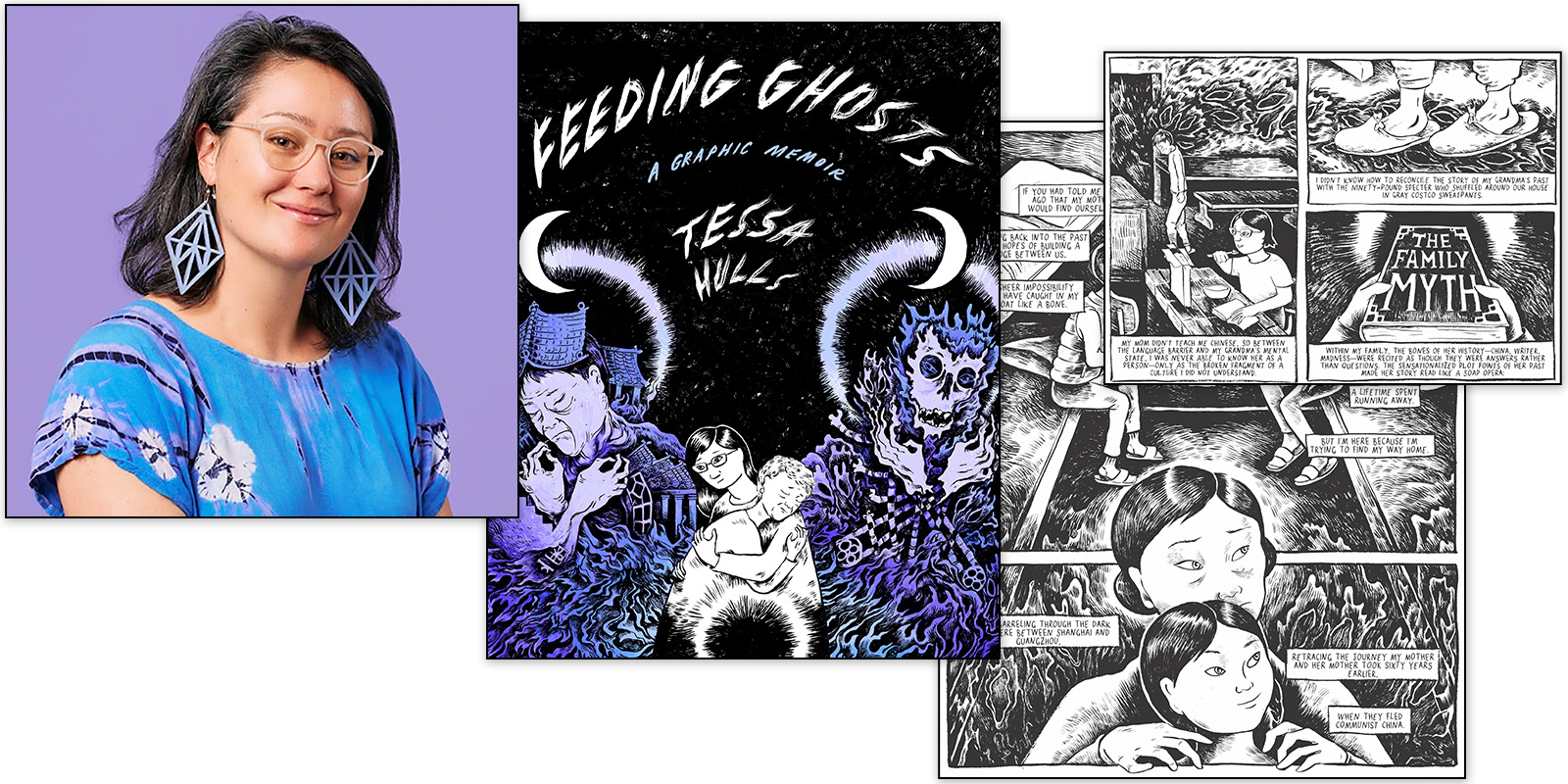

Tessa Hulls is an artist, writer, performer, and adventurist who works to connect the past and the present in her work. She is the author of the forthcoming graphic memoir Feeding Ghosts. In her historical work, Tessa is highly attuned to macro- and micronarratives and how the genre of graphic histories allows those narratives to meld. Tessa describes herself as equal parts “visual artist and writer,” making the graphic histories genre a perfect home for her.

Tessa Hulls, (left) and a selection of pages from Feeding Ghosts. Courtesy and © the artist.

Tessa Hulls, (left) and a selection of pages from Feeding Ghosts. Courtesy and © the artist.

When it came to writing Feeding Ghosts, a multigenerational Chinese family story, she felt it had to be written as a graphic novel “because it was such a complicated, multi-layered big sweep of the historical, and then the intimacy of the personal.” She knew that tying these threads together in the absence of a reliable narrator would be a challenge. Although not intentionally created for the classroom, it’s not hard to imagine its place in a history curriculum. Like most teachers, one of her goals is accessibility. Given the complexity and density of her topic, it was important to her to share this story in a way that enabled nonacademics to relate to it. She said the following about making her work more accessible beyond simply the genre: “My job is to essentially guide someone through a landscape, to leave them a trail and to help them navigate the terrain that I'm bringing them to.” She believes that with visuals the author is cultivating an immediate emotional relationship with the person who's digesting the material, and there is a level of personal engagement that happens with graphic storytelling that you don't get in a written text.

Tessa’s graphic memoir could be used as an incredible way to study Chinese history, art, memoir, historiography, and many more topics. Graphic novelists and biographers have the unique ability to tell highly complex narratives in ways that feel accessible to the reader.

Argha Manna

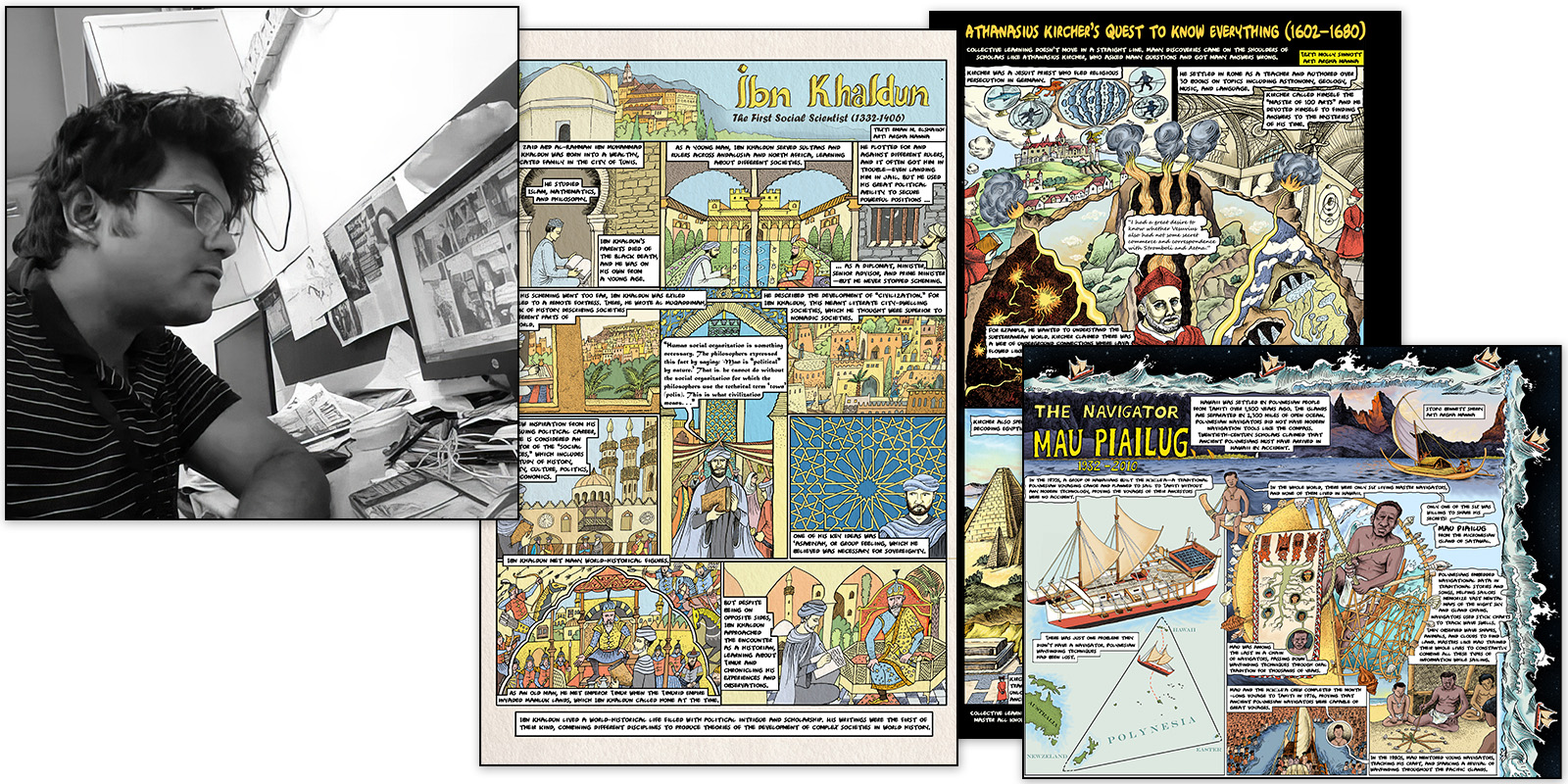

Argha Manna is a cancer researcher, scientist, journalist, and academic, as well as an accomplished comics artist. He explores the history of the development of scientific thought and reasoning. From projects with the University of Exeter and the British Library, to work with MIT that was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, the topics Argha researches are often dense, complicated, and not usually suited for the general population. However, much like Tessa, Argha aims to make his work accessible to everyone.

Argha Manna, (left) and a selection of a selection of BHP graphic biographies. Photo courtesy of the artist, BHP graphic bios, CC BY 4.0.

Argha is drawn to comics because they offer a space where ideas can be examined through both artistic and academic lenses. In his words, “graphic comics are not only the story of the visuals, they are something hybrid, something new.” The visuals allow you to have an image of the world that might differ from the one you mentally create when reading prose, one that might also lack historical accuracy. For example, he has created a few works about the Islamic world in Spain and has found that representing architecture and architectural styles accurately in this work is vital to giving the reader an accurate image of that time period.

In addition to making this work accessible, he seeks to spark curiosity with students. Argha points out that comics are one of the most democratic media we have for expressing ourselves. Anyone can draw. Even stick figures can convey a rich story. While this marriage of visual and text can be incredibly rich and complicated, there is also a simplicity to it—having students draw and provide some words, rather than create a finished work of art or piece of prose, is a much easier and more accessible task, yet still provides a window into their understanding. It’s no wonder that comic usage in the classroom has increased exponentially over the last few years.

Conclusion

More than just a cool way to tell stories, historical comics are emerging as a simple yet rich way to bring complicated and often untold stories from the past into the classroom (and the world). They are particularly prime for reaching different types of students in different types of contexts, helping to connect their lived experiences to the past.

OER Project, as do many other authors and artists, employs this medium for a number of reasons. There are some themes that cut across all the work. First, graphic histories support multiple timelines, allowing for a story that moves between longer-driving narratives and shorter, individual, pieces of history. Second, the genre supports representation and respect. Students should see themselves represented in history and they should also see people and places that are different from themselves and their community. Third, accessibility: Graphic histories, because they are in part visual, allow students of a variety of ability levels to interact with the historical narrative. Words are hard for some; images can provide a natural scaffold.

Finally, graphic histories are simply a beautiful way to share historical stories. They’re fun, engaging, and of course, visually appealing. This is a genre to be elevated and celebrated, and clearly has a home in both the OER Project’s curriculum and, we hope, your classroom.

Notes

[1] Barton, K. C., & Levstik, L. S. (2004). Teaching History for the Common Good. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; VanSledright, B. (2008). “Narratives of Nation-State, Historical Knowledge, and School History Education. Review of Research in Education, 32(1), 109–146.

[2] Barton, K. C. (2008). “Research on Students’ Ideas About History.” In L. S. Levstik & C. A. Thyson (ed.), Handbook of Research in Social Studies Education (pp. 239–258). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.; Haste, H., & Bermudez, A. (2017). “The Power of Story: Historical Narratives and the Construction of Civic Identity.” In M. Carretero, S. Berger, & M. Grever (eds.), Palgrave Handbook of Research in Historical Culture and Education (pp. 427–447). London, England: Springer.

About the author: Rachel Phillips, PhD, is a learning scientist who leads research, evaluation, and professional development efforts for OER Project. She is elementary certified, has taught in K–12 schools, and has served as an adjunct professor for graduate courses in American University’s School of Education. Rachel was formerly Director of Research and Evaluation at Code.org, faculty at the University of Washington, and program director for National Science Foundation-funded research. She is currently co-PI on an IES grant helping to develop discussions for use in World History classrooms, and is an academic advisor to Waterford.org.

Cover image: A selection of OER Project graphic biographies. By OER Project, CC BY 4.0.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments