Mike Burns, WHP Teacher

Hanoi, Vietnam

I’ve had the opportunity to get in on the ground floor of the World History Project (WHP) as a pilot teacher for the past two years. As one of the pilot teachers for the Big History Project (BHP) in the past, I jumped at the opportunity to help pilot the new WHP course. One exciting thing about being a pilot teacher is that you are truly building the course as you teach it, which – like building a plane as you fly it – has its own special kind of excitement. But after two years, this has developed into a flight-worthy course that’s ready to take on more passengers and copilots. Here are a few things that I find really exciting about the course, which I hope will help you get started.

Two Starting Points Mean Easier Implementation

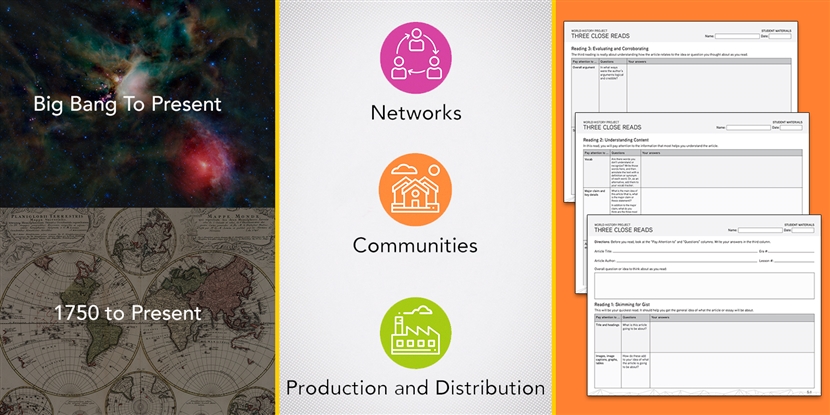

The World History Project curriculum is offered in two versions, which allows teachers to meet their specific state and district requirements. The primary difference between the two is the starting point: The Origins course begins with early humans. The starting point for the 1750 course is, well, 1750. I’ve been teaching the Origins course, which begins with a brief introduction to the concepts of Big History and proceeds along the familiar chronology of a world history survey course, beginning with early foraging communities and progressing to the present.

Frames and Narratives

History education guru Bob Bain (University of Michigan) introduces the concept of frames at the beginning of both courses to help provide a manageable structure. The three categories used throughout the course to “frame” our study are: communities, networks, and production and distribution. Traditional themes like politics, economics, and culture are easily accommodated using frames. One of the challenges for a teacher using frames is to stop equating them with themes or lenses. As Professor Bain explained to me, “Pick one of the lenses that you use and tell me its story.” Thinking of a lens like economics or culture, I realized that there is no overarching story to tell. When he then asked me to use one of the frames to tell a story instead, I realized I could produce a narrative that would be useful.

For example, the Draw the Frames activity at the beginning of the course asks students to draw a picture of a community. It has to include people, at least one place where people live, one place where they work, and one place where they spend leisure time. As students did this, it became much clearer to them how these frames work, and how they interact and connect. (I teach in Vietnam, so I was also fascinated in the differences between how Korean and Vietnamese students chose to represent these things.) As I continue to work with frames, I see the brilliance of the concept, and I appreciate more and more what it does and how it can facilitate student understanding.

Work Load Manageability

One of the things I really appreciate about this course is the flexibility it allows me for managing student workload. Every reading assignment is easily scaffolded using the Three Close Reads method (3CR). The 3CR method is designed to offer students more agency in their reading so they become active participants as they read. Most articles are in the 1,500- to 1,700-word range. Students are more motivated to read when they can more readily see how long it will take. Articles are well written, and intentionally aimed at a student audience.

About the Author: Mike Burns currently teaches at Concordia International School Hanoi, Vietnam, and has also taught in the US (Seattle), Qatar, and China. He loves to travel! In addition to being a founding teacher of the World History Project course, Mike is a veteran teacher of Big History and AP world history.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,