By Bennett Sherry and Trevor Getz,

OER Project Team

The United States funds proxy wars against authoritarian and communist regimes. A Russian leader threatens nuclear retaliation. The US, Russia, and China build elaborate alliance systems against each other. Sound familiar? No, it’s not 1964. It’s 2024.

On December 26, 1991, the Cold War ended. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the United States stood as the sole superpower on Earth. Just three months later, political scientist and scholar Francis Fukuyama published a book in which he speculated on the “end of history” and “the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”[1] Today, his prediction looks less certain. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has entered its third year. Ukrainian and Russian soldiers die in droves as the US and Europe supply weapons to Ukraine. The Syrian Civil War is entering its thirteenth year, with the US and Russia funding opposing sides and coming dangerously close to direct confrontation in the air. Global tensions are ramping up over a new conflict in Israel and Gaza, and China is deliberating an invasion of Taiwan. You don’t have to strain too hard to see the specter of the Cold War still haunting our world today.

Just a few of many recent headlines as pundits and academics seek to contextualize a world on the brink.

Just a few of many recent headlines as pundits and academics seek to contextualize a world on the brink.

Everywhere, conflict seems to be rising while stability falls. In 2023, there were 183 regional and local wars, the highest number in 30 years.[2] Looming over these local conflicts are the global tensions between Russia, the United States, and China—the owners of the world’s three largest nuclear arsenals. Their relationships are unstable, at best, and at times are downright surly. Are we in a new cold war? Did the old Cold War ever actually end? If not, what are the roots of this rising conflict and instability? These are questions worth pursuing.

What’s a cold war?

Asking these questions in the classroom can help students make connections between the past and today, as we examine Cold War history to understand our present and prepare for the future. The Cold War was a global struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union in which the two superpowers sought to define the future of the global order in the image of their respective economic ideologies: free-market capitalism for the US and state-directed communism for the USSR. In OER Project’s article introducing the Cold War, we define three key characteristics of the conflict, which lasted from 1947 to 1991:

- The threat of nuclear war

- Competition over the allegiance of newly independent nations

- The military and economic support of each other’s enemies around the world.

As you guide students through this complicated 45-year conflict, you might check out our new Cold War lesson plan, in which students create a timeline and step into the shoes of Cold War leaders. But let’s examine these three criteria to determine whether we’re witnessing “Cold War: Round 2.”

Doomsday checklist

Let’s start with the first factor—the threat of nuclear war. First, the good news: The number of nuclear warheads in the world has decreased dramatically since the end of the Cold War. Yet, that trend has slowed recently, as both the US and Russia rethink their nuclear strategies. Russian president Vladimir Putin has recently been flaunting Russia’s nuclear capabilities in warnings to the West over Ukraine. Though nuclear weapon stockpiles have decreased—from a Cold War high of 64,000 to about 12,000 today—there’s still plenty left to destroy our world several times over. The threat of nuclear war? Check.

The second factor—competition over the allegiance of newly independent nations—is a bit more muddied. The great era of decolonization has drawn to a close. In the past, struggles for independence were entangled with the Cold War, as anticolonial movements and the emerging factions sought support from the superpowers. The US and USSR, for their part, sought to contain the spread of communism to new countries (the US) and to ignite global communist revolution (the USSR). Today, by contrast, there aren’t dozens of new nations seizing independence each year.

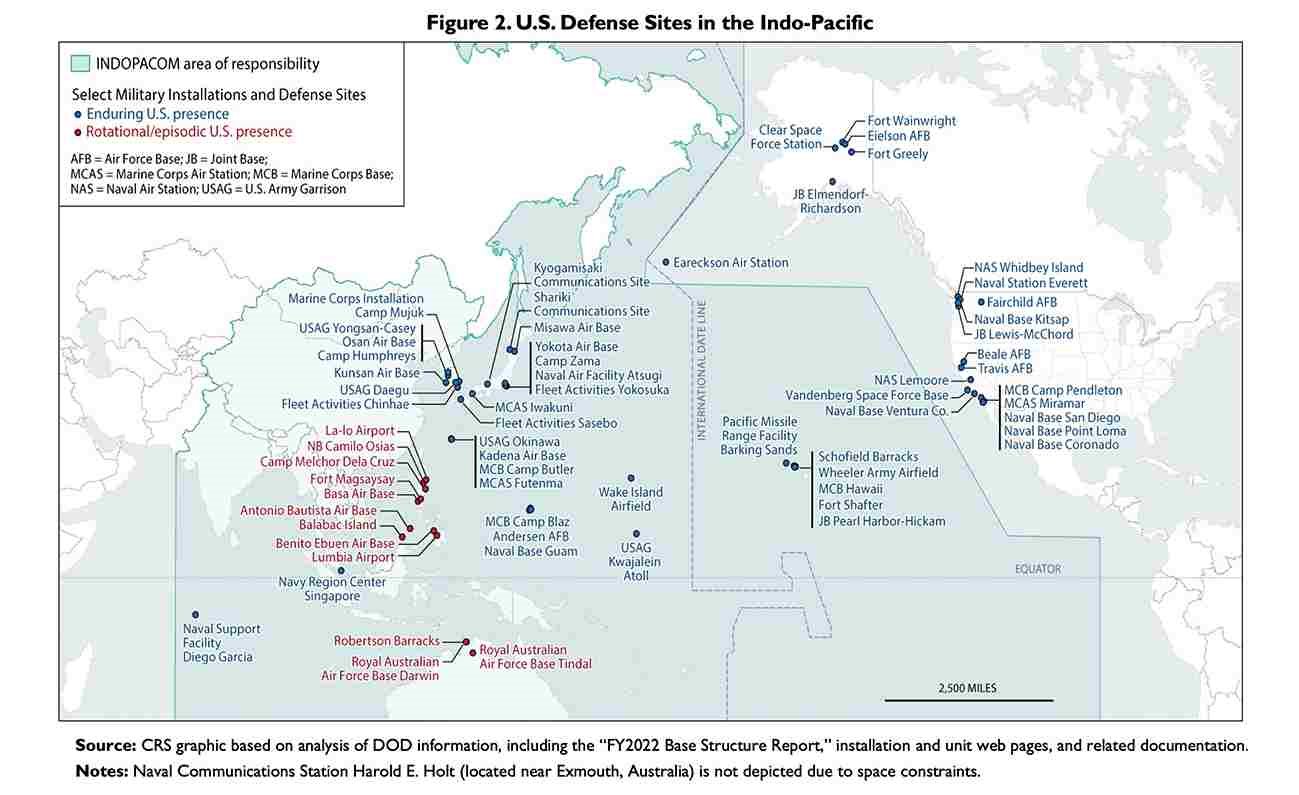

Still, there are some similarities between the global systems in these two periods. The US, Russia, and China are each working to expand their power by recruiting global allies. Just last month, Sweden followed Finland in joining NATO, expanding membership to 32 nations, with an eye toward preempting future Russian aggression. The Biden administration has been rebuilding an alliance system in the South Pacific, aiming to deter China’s expansionist aspirations. China and Russia have drawn closer in recent years, as they both seek global allies to counter Western alliances. China in particular has sought out alliances with African oil-producing nations. Competition over the allegiance of newly independent nations? Check(ish).

Map of NATO member states as of March 2024. By Janitoalevic, CC BY 4.0.

A map of US military sites in allied and friendly countries in the Indo-Pacific region, which build a cordon around China. By Congressional Research Service, public domain.

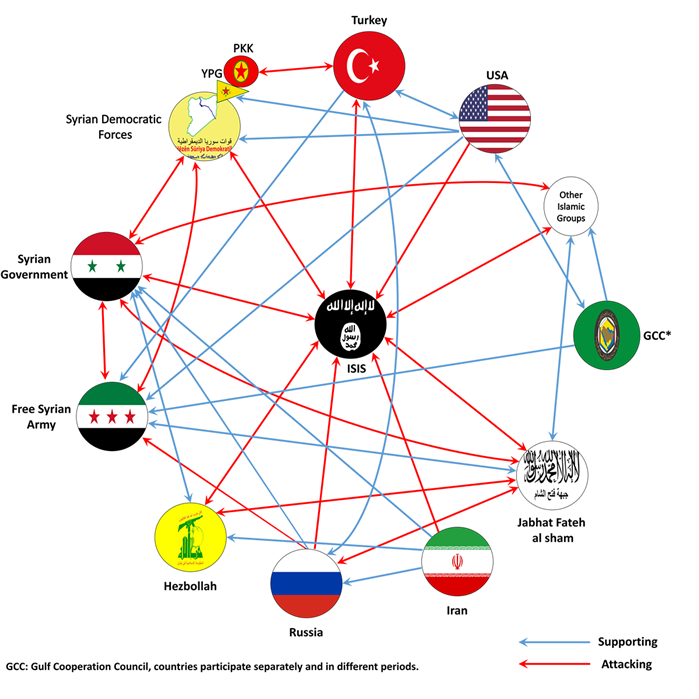

Finally, we have the question of military and economic support of rivals’ enemies around the world. The US and its NATO allies have sent over $175 billion in military and economic aid to Ukraine, as the Russian invasion of Ukraine enters its third year. Russia has suffered hundreds of thousands of casualties in the conflict, which is often compared to the Vietnam War and the Soviet-Afghan war. There are also smaller proxy wars in which Russia and the United States find themselves supporting each other’s enemies. For example, a tangled web of alliances and military aid has pitted the two countries against each other in the Syrian Civil War. In the Pacific, concerns have grown that Chinese leader Xi Jinping will soon seize an opportunity to invade Taiwan, which has maintained its independence from the People’s Republic of China since 1949. Although it doesn’t have formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan, the US government maintains a “robust unofficial relationship,” which includes the Taiwan Relations Act. Since 1979, this congressional act requires the US to provide defensive military aid to Taiwan. The military and economic support of each other’s enemies around the world? Check.

Alignment of different factions involved in the Syrian Civil War. By Michel Bakni, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Cool down the Cold War rhetoric

Although the evidence above might seem to confirm that we’re in another cold war, many historians aren’t sure. The prolific Cold War historian Arne Westad has rejected the idea.[3] But don’t be relieved just yet. Just because there isn’t a cold war doesn’t mean that peace is breaking out!

What do historians like Westad think is different now, compared to the years before 1991? Well, first, the Cold War was in many ways defined by its bipolar nature. The US and USSR were superpowers—the first in history—whose nuclear arsenals and military reach dwarfed the capability of any other nation on Earth. Today, Westad says, we live in a multipolar world, more akin to the global system on the eve of 1914. (That’s why you shouldn’t necessarily feel reassured by the differences between today and the Cold War era.)

Chinese and Filipino coast guard vessels almost collide in the South China Sea. The two countries, along with Taiwan, Japan, Vietnam, and other states—several aligned with the US—seek to control the valuable resources of the region. © Getty Images

Chinese and Filipino coast guard vessels almost collide in the South China Sea. The two countries, along with Taiwan, Japan, Vietnam, and other states—several aligned with the US—seek to control the valuable resources of the region. © Getty Images

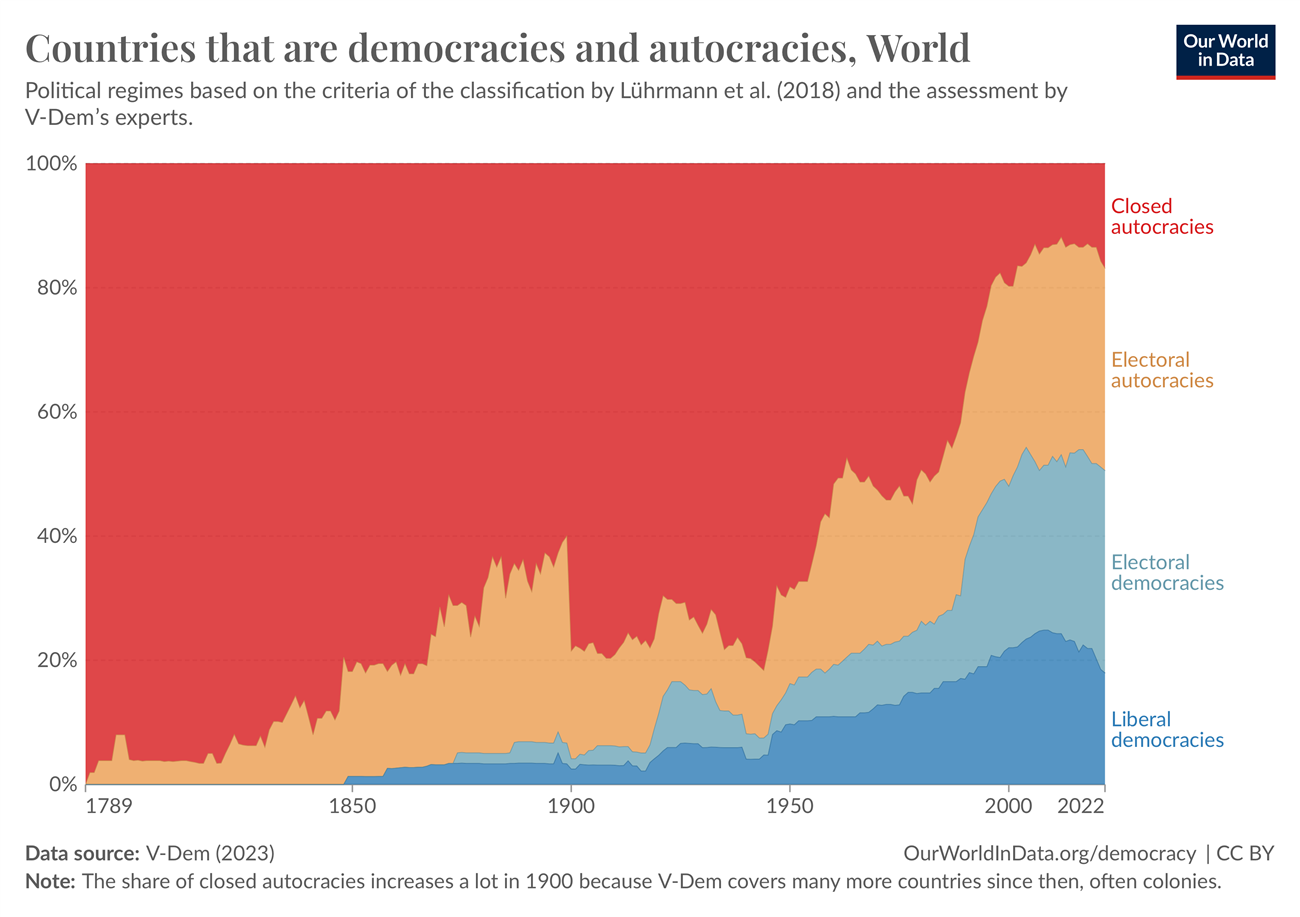

The second major difference is that in today’s world, an ideological schism doesn’t exist. The Cold War was an ideological struggle between two fundamentally opposed world views. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is not ideological. Even the official Kremlin justifications sound more like the imperialist racial theories of the nineteenth century. China’s bellicose behavior in the Pacific is partly driven by a desire to control the oil, fishing, and minerals of the vast South China Sea. China might be controlled by the Communist Party, but it isn’t the Soviet Union. The USSR rejected the international status quo. China today is a global power, internationally engaged. Today’s Chinese Community Party doesn’t necessarily want to overturn the global order—they’re too enmeshed in it, and the US is their largest trading partner. Chinese expansion seems more driven by nationalism and resource imperialism than by ideology. The conflicts in Ukraine and the Pacific aren’t part of a single global ideological struggle. Rather, these are separate conflicts driven in no small part by the recent rise in authoritarianism.

Countries that are democracies and autocracies. By Our World in Data, CC BY.

Countries that are democracies and autocracies. By Our World in Data, CC BY.

Westad claims that calling today’s situation a cold war is misleading—it’s politically convenient shorthand. However, don’t celebrate just because we might not be engaged in Cold War: Round 2. The Cold War—the original—offered stability, in a way. Terrifying stability—often violent and guaranteed by the two greatest arsenals in history pointed at each other—but stability nonetheless. As former US Defense Secretary Robert McNamara put it in a 1998 interview describing mutual assured destruction (MAD):

It's not mad! (laugh) Mutual assured destruction is the foundation of deterrence. Today it’s a derogative term, but those that denigrate it don’t understand deterrence. If you want a stable nuclear world—if that isn't an oxymoron … it requires that each side be confident that it can deter the other. And that requires that there be a balance and the balance is the understanding that if either side initiates the use of nuclear weapons, the other side will respond with sufficient power to inflict unacceptable damage … It’s not mad, it’s logical.[4]

So is Westad right, or are we in fact engaged in another a cold war? There’s a reason why we ask these kinds of questions, especially in the classroom. The past is, really, some of the best evidence we have for understanding the present. By having students look at events that have already happened, they can see both the opportunities and the dangers lurking in our present situation. But we have to be careful with these analogies. History doesn’t repeat itself, after all. But, as Mark Twain famously wrote, it often rhymes.

[1] Original quote from Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?” The National Interest 16 (Summer 1989): 4. Fukuyama’s book published in 1992 attempted to answer the question, “Whether, at the end of the twentieth century, it makes sense for us once again to speak of a coherent and directional History of mankind that will eventually lead the greater part of humanity to liberal democracy?” Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York: The Free Press, 1992), xii.

[2] IIIS, The Armed Conflict Survey 2023, https://www.iiss.org/en/publications/armed-conflict-survey/

[3] Michael Beckley, Arne Westad, and Bonny Lin, “The United States and China Are Locked in a New Cold War: A Debate with Dr. Michael Beckley and Dr. Arne Westad,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 3, 2024. https://www.aei.org/multimedia/the-united-states-and-china-are-locked-in-a-new-cold-war-a-debate-with-dr-michael-beckley-and-dr-arne-westad/

[4] Interview with Robert McNamara, National Security Archive, 1998. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/coldwar/interviews/episode-12/mcnamara1.html

About the authors:

Trevor Getz is a professor of African and world history at San Francisco State University. He has been the author or editor of 11 books, including the award-winning graphic history Abina and the Important Men, and has coproduced several prize-winning documentaries. Trevor is also the author of A Primer for Teaching African History, which explores questions about how we should teach the history of Africa in high school and university classes

Bennett Sherry holds a PhD in history from the University of Pittsburgh and has undergraduate teaching experience in world history, human rights, and the Middle East. Bennett writes about refugees and international organizations in the twentieth century and is one of the historians working on the OER Project courses.

Cover image: This image of the Berlin Wall was taken in 1986 by Thierry Noir at Bethaniendamm in Berlin-Kreuzberg. CC BY-SA 3.0

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments