By Bennett Sherry, OER Project Team

Maine, USA

The United States celebrates Labor Day on the first Monday in September. It marks the end of summer—one last chance to enjoy picnics and warm weather. If you’re lucky, you might take advantage of a day off before the school year shifts into high gear. Although protests have erupted from time to time, often in response to some related social conflict, for the last century or so Americans have been relatively content to take advantage of a nice, nonthreatening day off.

But Labor Day hasn’t always been so tame. The story from protests to picnics stretches back nearly 140 years.

Labor Day began in the late nineteenth century, as a growing labor movement sought to challenge the inequality of the Gilded Age and demanded better working conditions. Individual labor unions organized strikes, protests, and political campaigns, but these efforts were often disconnected. In 1882, union leaders organized the first Labor Day parade in New York. They wanted to encourage solidarity among unions to demonstrate that they had more power when they coordinated. Unsurprisingly, however, employers weren’t willing to give workers a day off to protest their working conditions. So the first Labor Day was also a general strike. At that first parade, 10,000 workers marched through the streets, and within a few years, several state governments recognized the first Monday in September as a holiday.

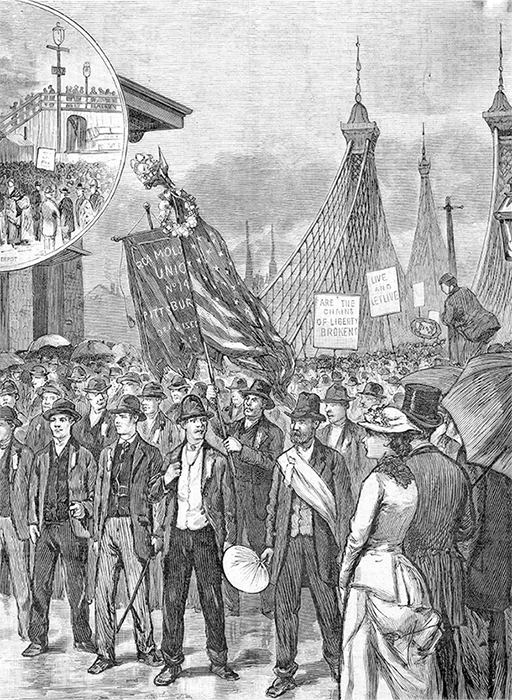

An illustration of the 1882 Labor Day parade in Pittsburgh. © Bettmann / Getty Images.

Radical elements

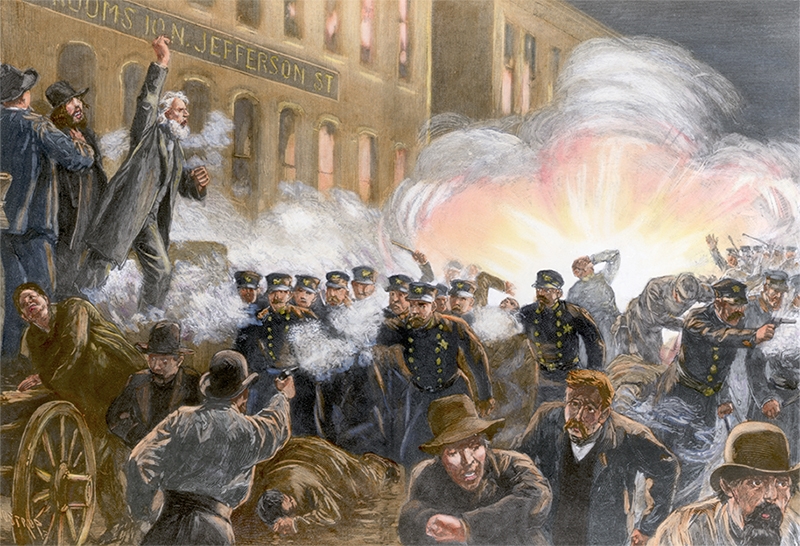

September wasn’t the only candidate for a labor holiday. Only Canada and the US celebrate Labor Day in early September. Most other countries recognize May 1—May Day—as International Workers’ Day. And yet, the origins of International Workers’ Day lie with the American labor movement and Chicago. In May 1886, the Haymarket Riot broke out in Chicago as workers took to the streets to demand an eight-hour workday. The riot ended in bloodshed after a bomb was detonated and police fired into the crowd. In 1889, the Second International in Paris chose May 1 as International Workers’ Day to commemorate the workers who had died there.

An illustration of the Haymarket Riot on May 4, 1886. After a bomb was detonated, the police opened fire on the crowd. Seven police and up to eight civilians died, with dozens more injured. © Bettmann / Getty Images.

An illustration of the Haymarket Riot on May 4, 1886. After a bomb was detonated, the police opened fire on the crowd. Seven police and up to eight civilians died, with dozens more injured. © Bettmann / Getty Images.

In the late nineteenth century, the American labor movement was the most active in the world. But it was also a movement divided. Leaders struggled to unite diverse coalitions while avoiding the appearance that they were radical actors who wanted to overthrow the government. At Labor Day parades, reformers mingled with socialists, anarchists, factory wage laborers, skilled artisans, and many others. In cities like New York and San Francisco, the movement was also ethnically diverse. Organizers sought strategies to make their parades less threatening and gain public support. They displayed American flags and discouraged radical slogans and placards.

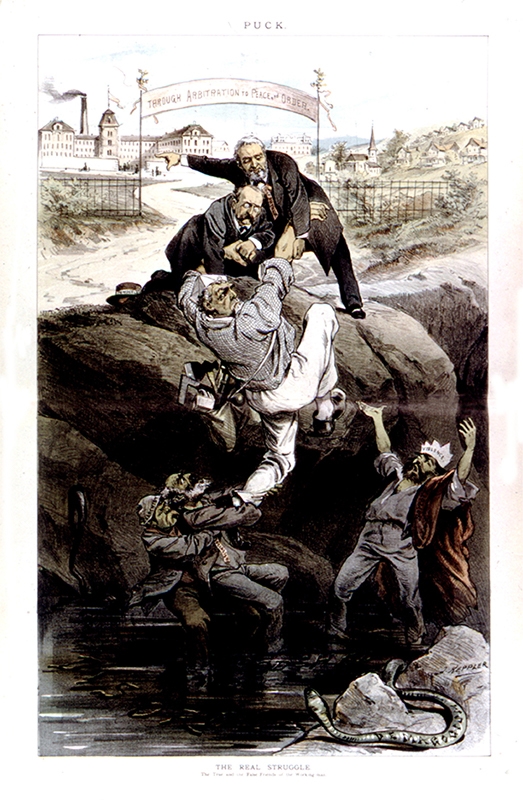

A cartoon published in 1886, after the Haymarket Riot. The cartoon warns American workers about violence as a socialist and anarchist try to drag Uncle Sam—dressed as a worker—down as two capitalists pull from above, pointing toward a sign proclaiming the virtues of arbitration, peace, and order. © Photo 12 / Getty Images.

A cartoon published in 1886, after the Haymarket Riot. The cartoon warns American workers about violence as a socialist and anarchist try to drag Uncle Sam—dressed as a worker—down as two capitalists pull from above, pointing toward a sign proclaiming the virtues of arbitration, peace, and order. © Photo 12 / Getty Images.

National recognition

It was this tension between radical ideas and the desire to appear nonthreatening that led to the choice of September over May as America’s Labor Day. But it wasn’t easy winning a federal labor holiday. Thirty state governments recognized Labor Day as a holiday before the federal government followed suit.

In 1894, President Grover Cleveland signed Labor Day into law as a federal holiday. The signing came amid the Pullman Strike, during which President Cleveland brought about a public relations disaster when he deployed the US military against striking railroad workers. The decision to make Labor Day a federal holiday was partly to placate angry American workers, but it was also a calculated strategy to avoid elevating the May 1 holiday. With its links to communist organizations abroad and its association with the Haymarket Riot, President Cleveland feared that recognizing May Day would strengthen the radical elements of the American labor movement.

By the early twentieth century, union leaders began to worry that their Labor Day efforts might have been too successful. Many workers were increasingly content to stay home during their federally mandated day of rest, rather than march in the streets. May Day, meanwhile, continued as a day of protest in the US and around the world. In 1907, one union leader worried that Labor Day would lose its meaning and power if it became “a holiday for jollification without other purpose, design, or result.” In the second half of the twentieth century, Labor Day evolved into a much less radical holiday. Unionization rates fell from almost 40 percent to around 10 percent today.

Working connections

Your world history students might not be ready, content-wise, to jump into the labor movement in early September, but the story of Labor Day—and unionization in general—is a great opportunity to highlight the importance of connections—historically, internationally, and between different groups of people. For example, historically, medieval European guilds resembled the later labor unions in many ways. Marchers in early Labor Day parades often adopted symbols from historical guilds to appear more traditional and less radical. In addition to the historic racial and ethnic diversity of different unions that participated in the creation of Labor Day, it’s important to note that women’s rights groups were an essential part of the labor movement. Women’s rights and workers’ rights groups cooperated across national borders, lending support in solidarity with each other.

Suffragettes and members of the Laundry Workers Union of New York march in a Labor Day parade, demanding an end to child labor. © Library of Congress / Corbis Historical / Getty Images.

Suffragettes and members of the Laundry Workers Union of New York march in a Labor Day parade, demanding an end to child labor. © Library of Congress / Corbis Historical / Getty Images.

In the second half of the twentieth century, the labor movement became entangled with the Civil Rights and decolonization movements. In the early twentieth century, many unions in the United States had engaged in aggressive racist practices aimed at excluding Black workers. Yet pressure from the Civil Rights Movement forced unions to end racist policies, and Black workers soon had the highest unionization rates of any group in the US—peaking at around 40 percent of Black men and 25 percent of Black women in the 1970s. High unionization rates among Black workers helped decrease the wage gap between white and Black Americans. Since the 1970s, however, unionization rates have declined across all demographics, and with it, racial pay inequalities have risen as well.

Your summer vacation is ending too soon after a long, difficult school year. I’m not demanding you get out in the streets. Particularly this year, you deserve the picnics, BBQs, and a day off. But as your students enter another year of high school, it’s worth giving them time to consider how the labor market might change in the wake of a global pandemic. After all, there’s a pretty good chance that you belong to the largest labor union in the US—the National Education Association. From education work to the gig economy to work-from-home, a lot of change is in the air. Understanding the historical roots of their day off on September 6 might help students start building a usable history. And who knows—maybe it will encourage them to get out and demand change. Maybe on May 1.

Sources

Haberman, Clyde. “A Labor Day Labor Forgot to Celebrate.” The New York Times, 2007.

Kazin, Michael and Steven J. Ross. “America's Labor Day: The Dilemma of a Workers’ Celebration.” The Journal of American History (Bloomington, Ind.), 78, no. 4 (1992): 1294–1323.

McKeever, Amy. “Labor Day’s Surprisingly Radical Origins.” National Geographic. September 4, 2020.

Rosenfeld, Jake and Meredith Kleykamp. “Organized Labor and Racial Wage Inequality in the United States.” The American Journal of Sociology, 117, no. 5 (2012): 1460–1502.

About the author: Bennett Sherry holds a PhD in history from the University of Pittsburgh and has undergraduate teaching experience in world history, human rights, and the Middle East. Bennett writes about refugees and international organizations in the twentieth century. He is one of the historians working on the OER Project courses.

Cover image: American flags are attached to the hood of a Cadillac convertible during a Labor Day celebration in New York City. © mark peterson/ Corbis / Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments