By Bennett Sherry

Everything is awful

When we’re asked, “Are things getting better?” a pessimistic quip is often our default response. Many people think things are even getting worse. Hans Rosling, the medical doctor and educator who cofounded the Gapminder Foundation and Doctors without Borders Sweden, suggests that we default to negativity because our brains are always seeking drama.[1] Rosling argues that things are actually much better than we tend to think. He points to data indicating that overall, we humans live longer lives, are more educated, and are healthier than we used to be.

| The charts in this blog all come from Our World in Data, an online publication founded by Max Roser dedicated to providing research, data, and visualizations on some of our most pressing historical and contemporary issues. At OER Project, we know students can struggle to understand charts and data. One place to start is with Project X—a short course on reading and evaluating data visualizations. |

Still, we have plenty of reasons to be pessimistic about the trajectory of world history. In the last three years alone, the world has experienced political turmoil in some of its oldest democracies; a global pandemic; the outbreak of war in Europe; and the looming threat of nuclear winter. Many people—in both the world’s wealthiest nations and in its poorest—struggle to survive as globalization reshapes economies. Human emissions of carbon are driving climate change forward at a terrifying pace. Season three of The Mandalorian is a disappointment.

It's grim out there.

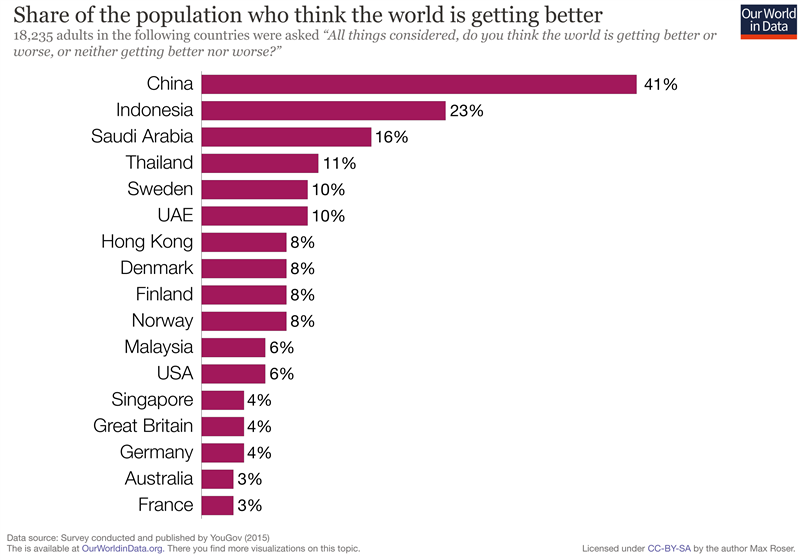

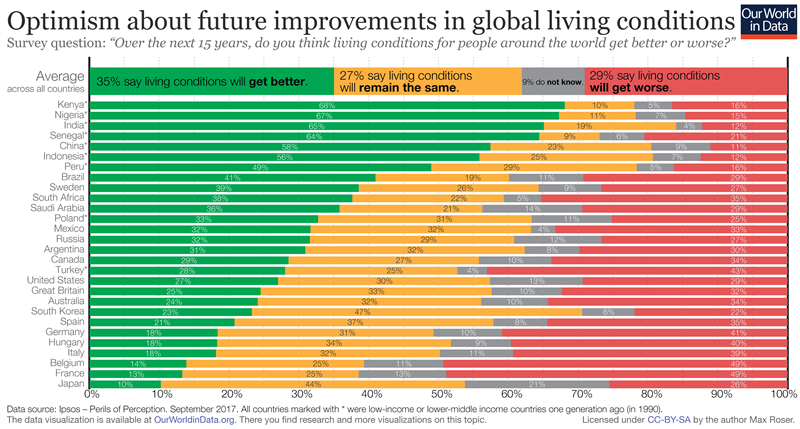

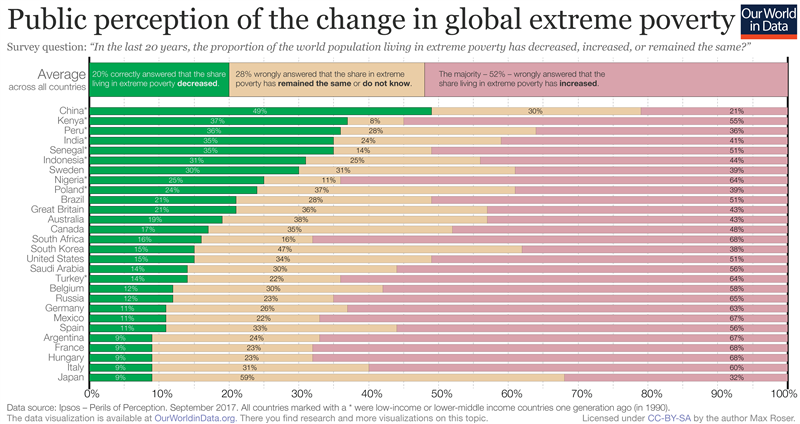

That might be why 39% of American adults believe that we’re living through the end times. Take a look at the three charts below. Worldwide, most people believe the world is getting worse, and they doubt that things will improve. Globally, 52% of people think that extreme poverty is getting worse. Most people believe that child mortality has either increased or stayed the same in the last 20 years.

As Rosling wanted us all to know, most people are wrong.

Percentage of people who think the world is getting better. By OWiD, CC BY.

Percentage of people who are hopeful about future improvements. By OWiD, CC BY.

Public perception of the impact of extreme poverty. By OWiD, CC BY.

The past is a foreign country—with worse infrastructure

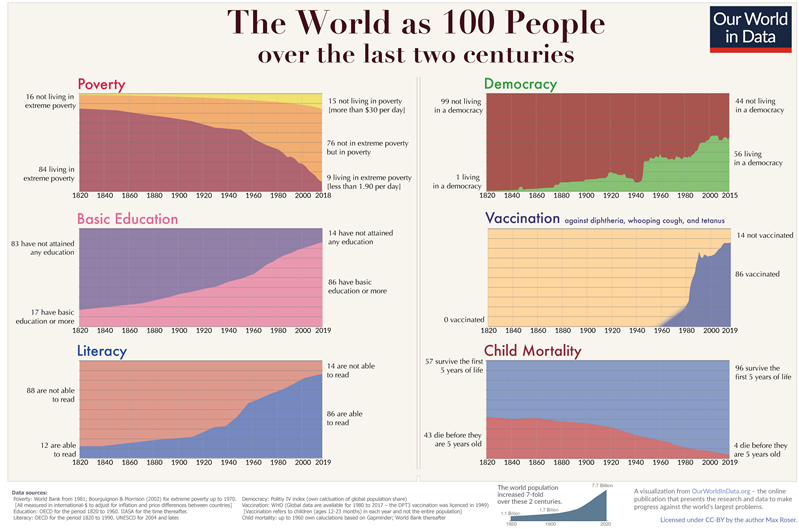

Looking at global statistics, the conditions of human life—as a whole—on this planet have improved dramatically over the past two centuries. The percentage of people living in extreme poverty has plummeted. Children born in this century have a far better chance of surviving to adulthood than at any time in human history. These children are far more likely to learn to read, receive vaccinations, and live in a democracy. Global human life expectancy has increased by 40 years since 1770. We have eradicated smallpox and made incredible progress on the path to eliminating other diseases such as malaria and polio. In many countries, women and LGBTQIA+ communities enjoy more rights than in previous centuries.

The World as 100 People. By OWiD, CC BY.

The World as 100 People. By OWiD, CC BY.

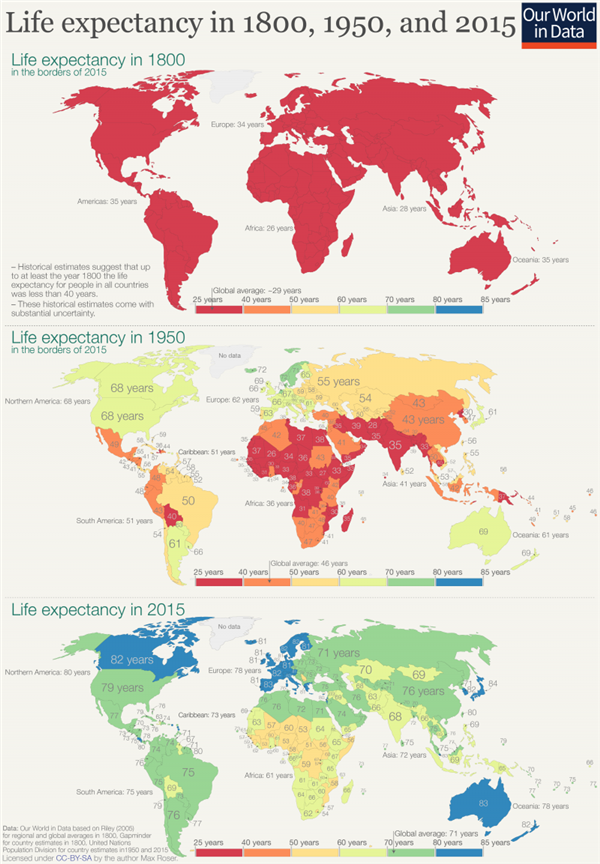

These three maps of life expectancy in 1800, 1950, and 2015 illustrate just how dramatically things have changed:

Improvements in life expectancy over 215 years. By OWiD, CC BY.

Improvements in life expectancy over 215 years. By OWiD, CC BY.

Progress: Reality or myth?

So, if the world is so much better now, why doesn’t it feel like it? Why do people in most places think things are getting worse? David Brooks puts it like this: “[L]ife in America today is objectively better than it was before but subjectively worse.” Those who point out that life is objectively better include not only Rosling, but also scholars like Steven Pinker and Max Roser. They argue that the widespread pessimism is a result of the nature of news media and human psychology. Simply put, the news we focus on is the big, bad stuff that goes wrong each day. Hurricanes, wars, forest fires, building collapses, riots—these all get more clicks and more coverage than the small, incremental changes that are quietly improving lives.

Claiming “the world is better” isn’t the same as “everything is good.” After all, narratives of progress can be hard to swallow if you’re a refugee from Bakhmut or an industrial worker watching the decline of manufacturing in Detroit. Indeed, critics warn that the upbeat narratives Rosling and Pinker offer simply protect the status quo and make it harder to address the problems created by liberal capitalism. Things are still bad in many places, and the huge improvements in human life haven’t been enjoyed equally. For example, most of the reduction in global extreme poverty happened in China. That’s a big part of the reason that China is one of the few countries where most people think things are generally improving. Inequality within and between nations remains a major problem.

Critics of “the world is getting better” narrative claim that our ideas about progress are rooted in Enlightenment thinking and assume a single path of social progress—that we are taught that the arc of history bends toward justice. Unlike our love of drama, this idea isn’t something hardwired in us, but rather learned recently. For most of recorded human history, this idea of progress didn’t exist as it does today. Ancient Romans didn’t believe history followed an inevitable path toward human improvement. Many cultures looked back, rather than forward, at some idyllic, mythical golden age. In the past three centuries, however, humanity has increasingly looked to the future for their utopias.

The long nineteenth century sparked a myth of progress. The Scientific Revolution, the Enlightenment, and the Age of Revolutions produced a sense (mostly in wealthy European nations, and then spread through their empires) that history moved in a positive direction—that a better world could be made for all. Yuval Noah Harari specifically locates the roots of this myth in the scientific and technological advances of the last two centuries and in the development of capitalism, which promised to grow the pie for everyone. These developments in science and economics encouraged people to trust that the future would be better.

But history isn’t a straight line. And in 1914, all the promise of the European Enlightenment came crashing down in the trenches of World War I. The disillusionment that followed and the rise of extremism in the years leading up to another world war shook the foundations of this belief in progress. Could that happen again?

Things could get much worse

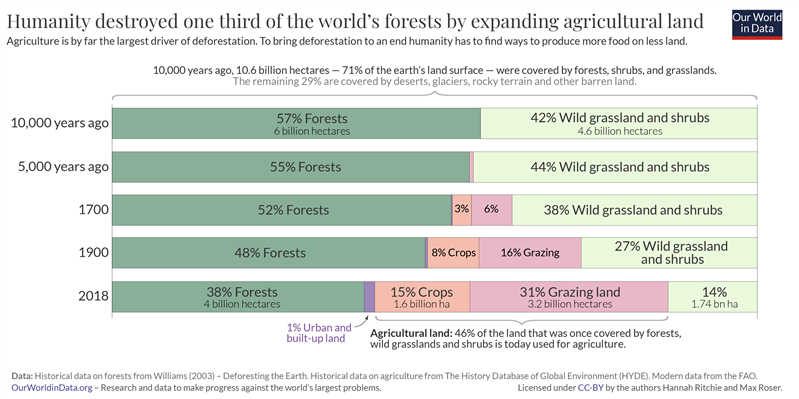

Critics are also quick to point out that the world today isn’t improving in every metric. And, despite all the remarkable innovations and improvements of the last two centuries, things could still get much worse, particularly if the pace of climate change continues unabated. These downward trends could erase all the hard-earned gains of the last century.

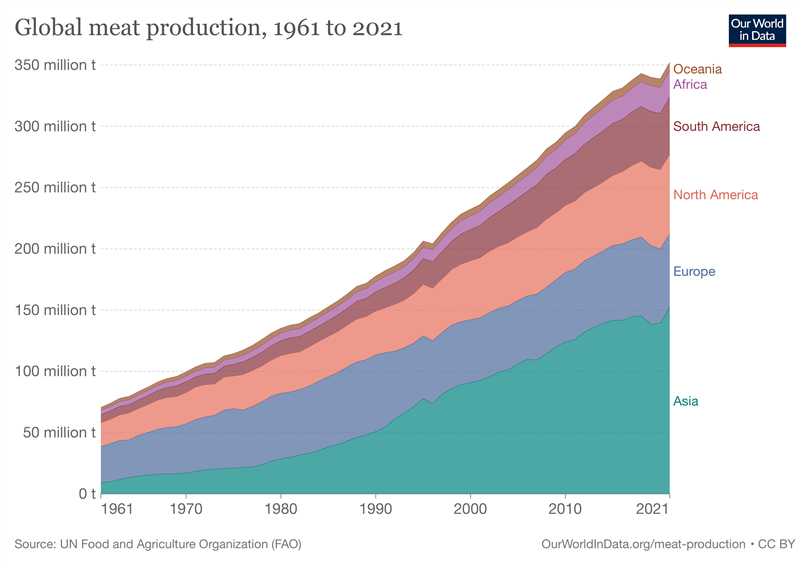

For many people around the world, things aren’t getting better. But for other species things are getting much worse. Massive factory farms, the destruction of habitats, and deforestation have all taken a toll on the species we share a planet with. Although viruses seem to be thriving. So, there’s that.

Global meat production growth in 50 years. By OWiD, CC BY.

Global meat production growth in 50 years. By OWiD, CC BY.

Decline of forests and growth in agricultural land use over time. By OWiD, CC BY.

Decline of forests and growth in agricultural land use over time. By OWiD, CC BY.

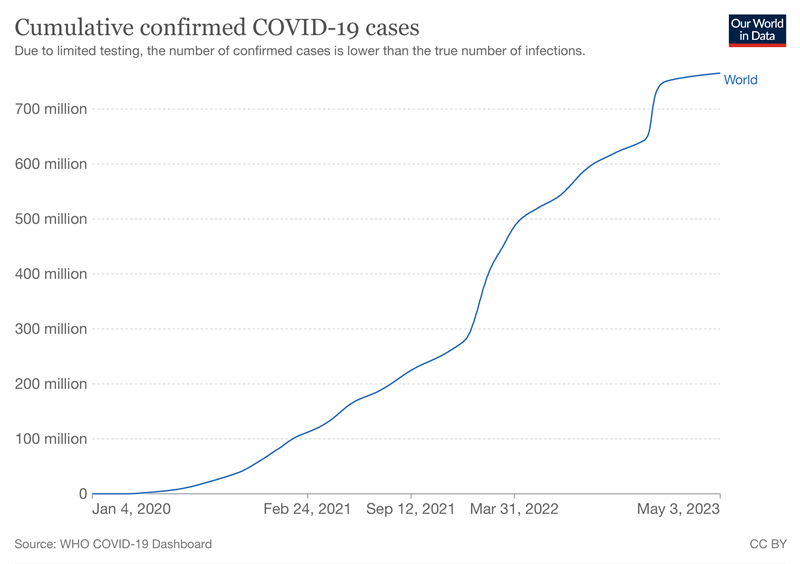

Number of COVID cases from the start of the pandemic to present day. By OWiD, CC BY.

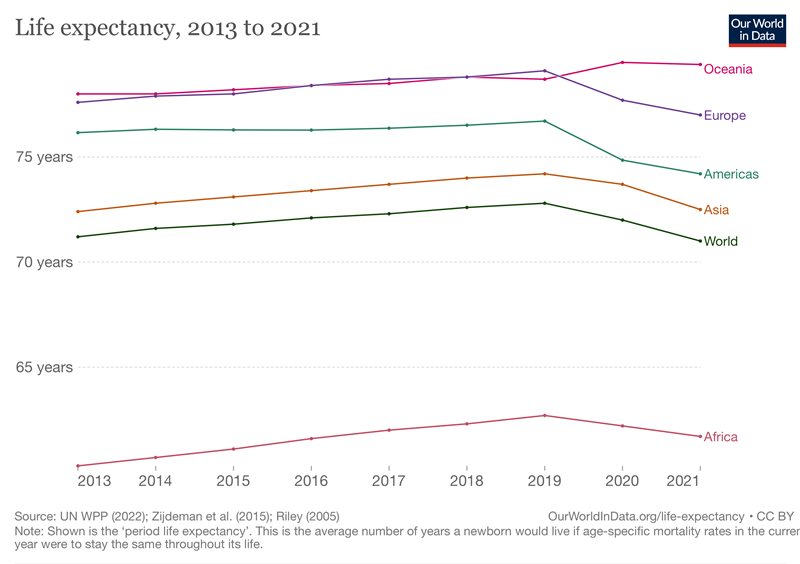

Digging into the data, there are also plenty of warnings that past results are no guarantee of future returns. For example, in large part thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic, life expectancy has dropped in most places since 2019. From 2019 to 2021, life expectancy declined by three years for Americans—the largest two-year drop in the last century. This decline was even worse among Indigenous American communities.

Changes in life expectancy from 2013 to 2021. By OWiD, CC BY.

Changes in life expectancy from 2013 to 2021. By OWiD, CC BY.

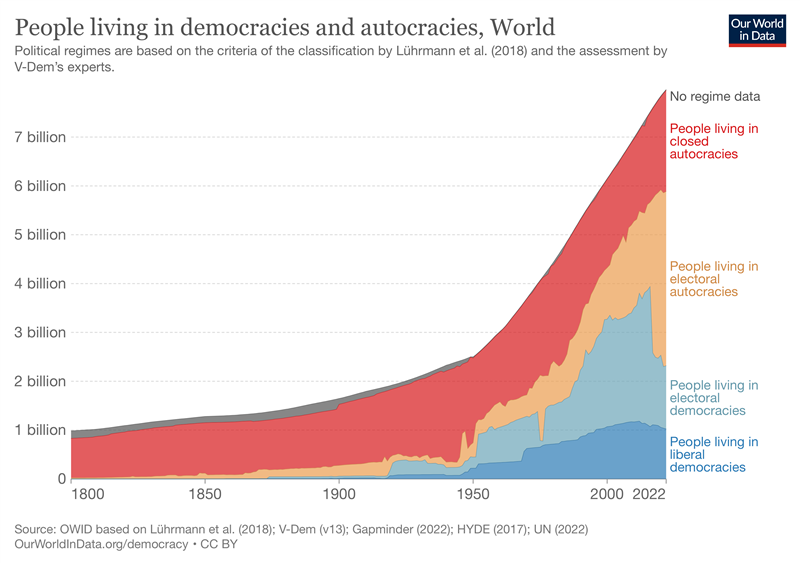

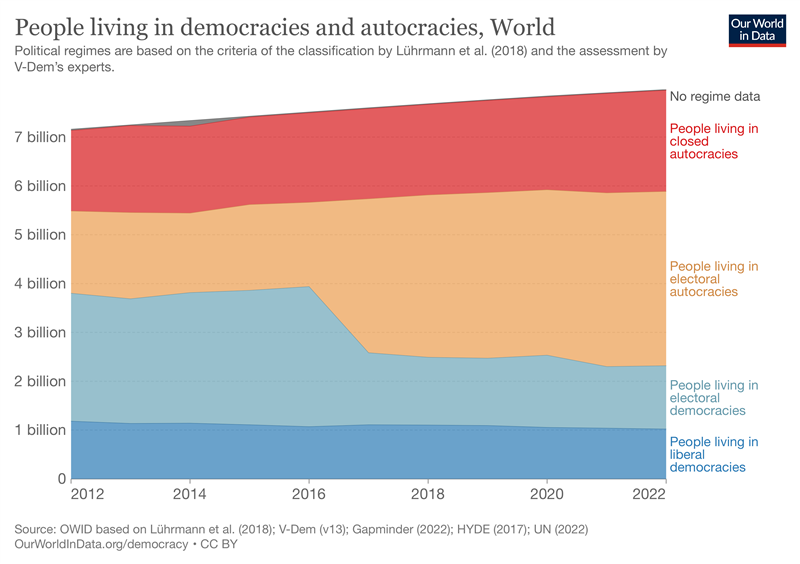

As you read above, over the past 200 years, more and more people have been living in democracies. Yet, if you switch time scales, the story changes. Over the past decade, the number of people living in democracies has fallen.

Share of people living in different political regimes over time. By OWiD, CC BY.

Share of people living in different political regimes over time. By OWiD, CC BY.

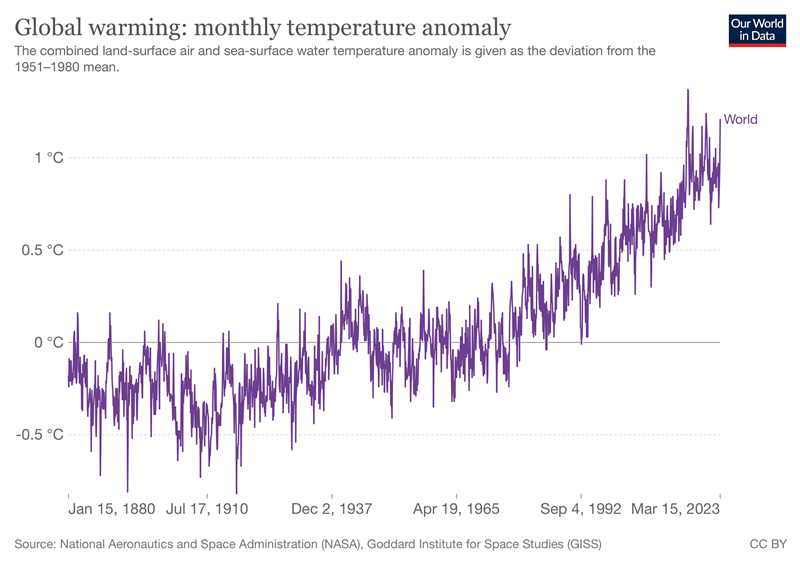

And finally, with perhaps the exception of thermonuclear war, modern humans have not faced a threat as all-encompassing as climate change.

Changes in global warming since 1880. By OWiD, CC BY.

Changes in global warming since 1880. By OWiD, CC BY.

These are stark reminders: The world has gotten much better for most people. There’s less war, longer lives, better medicine, and a host of other advantages to life in this century compared to previous periods. That’s no reason to be complacent. Things could still get worse.

Building usable pasts

At OER Project, our goal is to help students build usable pasts by gathering historical evidence to understand the present and prepare for the future. The truth is, both the optimists and their critics offer evidence that students can use. For many, this is the best time in human history to be alive, even in the face of staggering problems and the potential for a worse future.

The evidence that things have gotten much better arms students with optimism. They’ll need it if they’re going to believe that the world can continue improving. The doomsayers, meanwhile, remind us that progress isn’t inevitable, and we ignore the problems with the status quo at our peril. Complacency is not an option.

By understanding that we’ve succeeded in the past, we’re armed with the knowledge that we can improve the future. Evidence like this can stave off the despair of climate change. For example, in the second half of the twentieth century, the governments of the world united in an effort to address damage to the ozone layer. The result has been a resounding success. While students need to understand the existential threat of climate change, they also need stories like this and of the many people working to get us to net-zero carbon emissions. Humanity has faced and overcome threats in our past. Both those who sounded the alarm and those with the optimism to imagine a better future helped us avoid catastrophe, and we'll need everyone—optimists and critics—to work together to make the future better for us all.

About the author: Bennett Sherry holds a PhD in history from the University of Pittsburgh and has undergraduate teaching experience in world history, human rights, and the Middle East. Bennett writes about refugees and international organizations in the twentieth century and is one of the historians working on OER Project courses.

Cover image: Composite image of a chart illustrating how things are getting better. Left: An SDF fighter walks down a empty street amid destruction on February 16, 2019 in As Susah, Syria. © Chris McGrath / Getty Images. Middle: At the intersections of Avendia Jimenez and Carrera Septima, red Transmilenio buses pull into the Museum of Gold station in front of the16th century Iglesia de San Francisco, Bogota'soldest restored church. © John Coletti / The Image Bank / Getty Images. Right: Solar energy fields and wind turbines seen from the air in foggy conditions during a Autumn morning. Muntendam, the Netherlands, September 2022. © Daniel Bosma / Moment / Getty Images.

[1] Hans Rosling, et al., Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About the World—and Why Things Are Better Than You Think, Flatiron Books, 2018, 14–15.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments

-

Bryan Dibble

-

Cancel

-

Up

0

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Comment-

Bryan Dibble

-

Cancel

-

Up

0

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Children