By Eman Elshaikh, OER Project Team

The past does not exist—or at least not any longer. And yet, the past is everywhere: in movies, family recipes, architecture, even the clothes we wear. We can access the past in many ways, but history is one important way of making sense of it. We make and consume history every single day by piecing together bits of data, evidence, and experience into stories about the past. Still, it can be tricky to toggle that switch on in the classroom. Students study history, but they sometimes struggle to experience it and form a relationship with the past that they find meaningful or even interesting. How do we help students forge that connection?

To experience history, you have to do a bit of world-building. Luckily, you don’t have to come up with a world from scratch. Rather, your task is to reconstruct a world based on the traces left behind. That’s not easy either, but there are some techniques that can help you and your students get started.

Rebuilding a world, reconstructing a perspective

Begin by setting the scene. To start building a world, you have to understand the space you’re in. When students are confronted with a long block of primary source text or objects in a dusty museum, bits of information don’t really feel connected to anything. To ground them, it’s helpful for students to research the landscape, climate, or architecture of a particular place. This doesn’t have to take a ton of time. Google Maps is an excellent tool. Looking through historical or contemporary photographs can help students situate an object or text. Even if we don’t have access to images, the exercise of imagining or drawing a scene based on the available information helps situate students.

Once you establish the time and space, you have to populate it. Biographies, oral histories, photographs, and personal objects are all ways to connect with a perspective and reconstruct it. Prompt students to ask unusual questions: How do you think this person spent his or her day? What mood were they in when they wrote this? What might they find funny, objectionable, or weird?

Also remember to think beyond words. Objects tell their own stories. They are an excellent starting point for experiencing history because you can touch, move, and sense them in different ways. Beyond that, they also carry a ton of information that text doesn’t. For example, marks on a shoe can tell you a lot about its wearer or maker.

Students can also learn by engaging physically, by making diagrams or models, or by performing or debating. Something as seemingly mundane as a Victorian washing machine or nails from your home can reveal past lives. Material objects can help students think about how it might feel to wash clothes as an ordinary Victorian woman, or work iron as a five-year-old girl. Don’t overlook the ordinary—it’s a powerful tool for experiencing history. Examining everyday items like cooking utensils, nails, or washing machines helps make history palpable, connecting the distant past to students’ experiences.

Still from the Victorian washing machine video.

Still from the Victorian washing machine video.

Last, pull apart the layers. Once you’ve made a world, populated it with people and things, and moved around and within that space, start looking at it from different angles. You can ask: how many people have touched this object or been in this place? What came before or after this? In other words, after you build your world, start to break it down, because that helps you ask about what could have been different. Understanding what could have been helps students get a grasp on why it was the way it was—and why that matters.

Case study: Yesenia Bonilla’s testimony

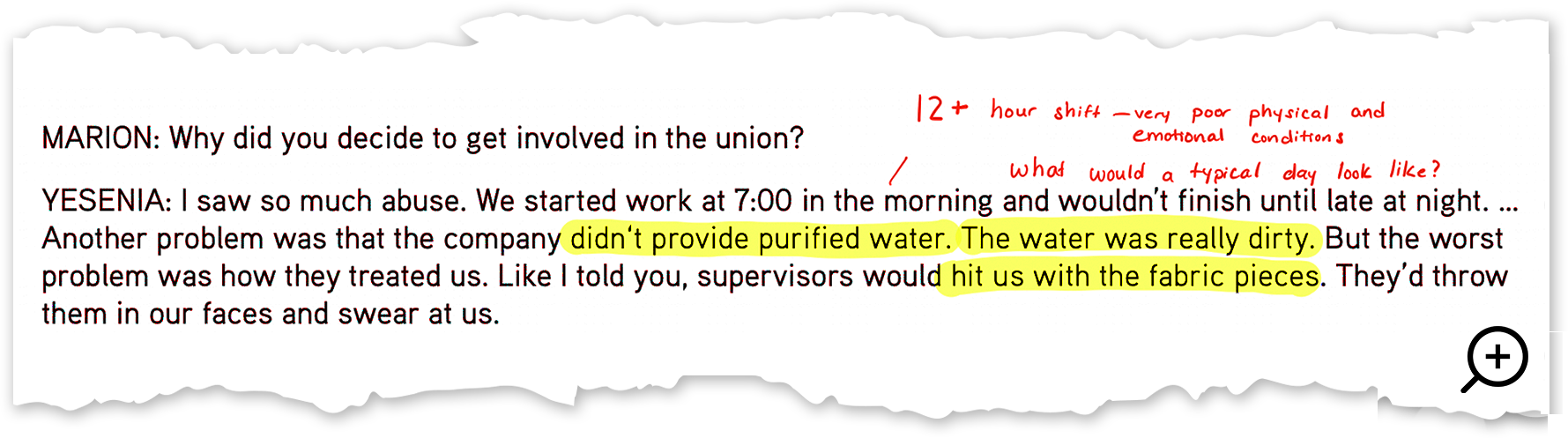

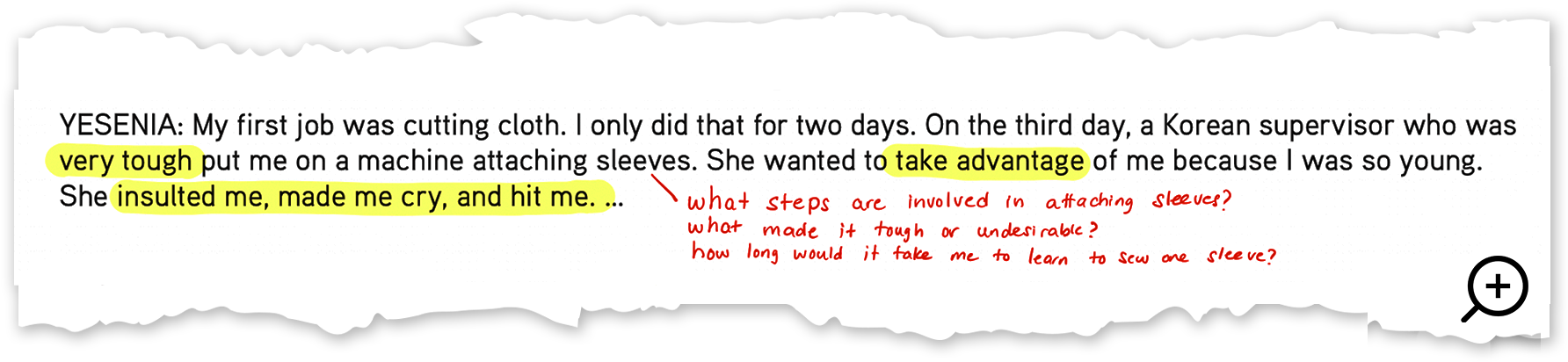

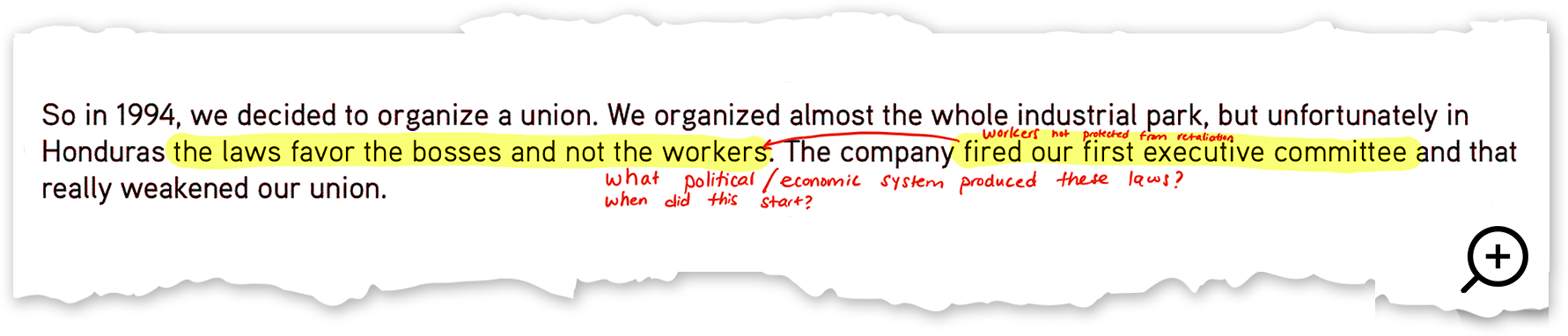

Let’s try out this technique on a traditional primary source document. I’ll be looking at an interview with Yesenia Bonilla, a young worker in a Korean-owned clothing factory in Honduras in the 1990s. In it, Yesenia describes her work conditions and her union activism.

To draw the contours of Yesenia’s world, you can start before students even begin reading. Have students do a quick image search of Honduras. You might have them do a little background research on maquiladoras or industrial cities in South America. As they dive into the text, students could look at photos or draw a sketch of a maquiladora.

Though we may not be able to find an image from the factory Yesenia worked in in 1996 in Honduras, we can look at images from similar foreign-owned garment factories at the time, like this one in San Salvador, El Salvador. This image was taken in a maquiladora much like Yesenia’s in 1995, amidst similar fights for unionization, better treatment, and adequate work conditions. © AFP / Getty Images.

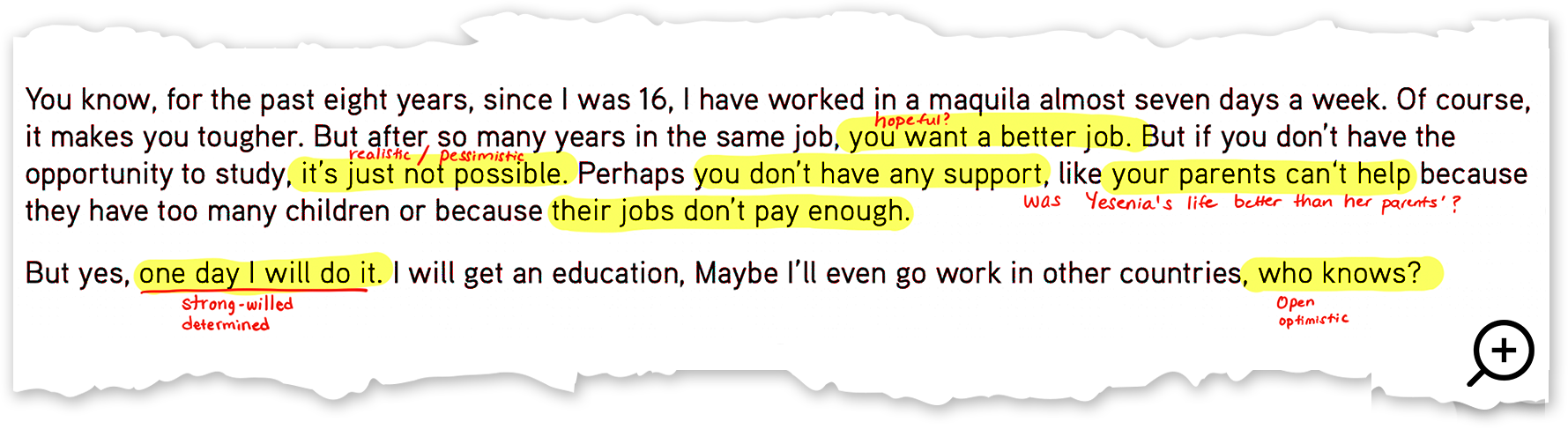

Because this is an interview, it’s already somewhat personal. But push students to notice: how did Yesenia spend her day? How did her work affect her physically, emotionally, financially? What mood was Yesenia in when she was interviewed?

To add a physical dimension, students could try to experience Yesenia’s work by examining the sleeve of a garment or attempting to sew one themselves. They might try to reenact the flow of life in a factory by making a timetable. They could look for objects produced in a maquiladora.

Let them linger on the ordinary dimensions of Yesenia’s day-to-day life. Ask them to pull out information about Yesenia’s family budget or her travel to and from the factory.

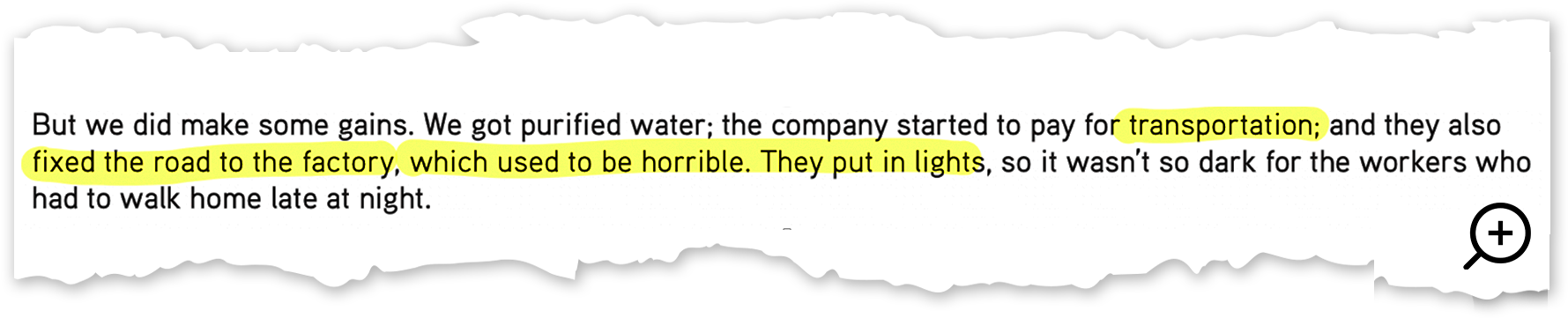

Last, students can start doing the difficult work of opening up the world. They might learn more about the factory Yesenia worked in and its history. They might think about labor markets, political ideologies, or shipping networks. They might ask about the other people in the story—factory bosses or Yesenia’s family members—and imagine their responses to her testimony. They can also switch scales and contextualize Yesenia’s story in broader narratives, arguments, or processes.

Words and objects can seem dry, but with the right questions, they offer a path into a new world. They give us the materials to reconstruct that world and the perspectives within it so that we can experience it. When historians reconstruct worlds, we make choices about how, when, and where we access the past, whose perspectives we empathize with and whose we struggle to understand. These techniques give students a way to make those choices themselves and see beyond distant, dry words to experience history.

About the author: Eman M. Elshaikh is a writer, researcher, and teacher who has taught K–12, undergraduates, and graduate students in the United States and in the Middle East. She teaches writing at the University of Chicago, where she also completed her master’s in social sciences and is currently pursuing her PhD. She was previously a World History Fellow at Khan Academy, where she worked closely with the College Board to develop a curriculum for AP World History.

Header image: Composite image of two artists painting in their studio, Self-Portrait at an Easel by Sofonisba Anguissola © Ali Meyer/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images (left) and artist painting on canvas © Westend61 / Getty Images (right).

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments