By Bennett Sherry

Human scales

History is written by the victors, or so it’s said. And there have been few victories so resounding as that of humanity over our natural environment. Yet, as we’ve reluctantly learned over the last century, it is a victory that might mean defeat. Since humans started to farm, and increasingly since we learned to harness fossil fuels, we have imagined ourselves as separate from the so-called natural world around us. But human society and nature are, and always have been, entangled. How can we use historical thinking skills to convey this entanglement? Scale switching can help your students understand how humans and other species have changed each other.

In WHP and BHP, we’re used to switching scales. We often jump from looking at the whole planet to focusing on huge empires, nation-states, cities—all the way down to the life of one individual. We learn new things as we travel between these scales, gaining new perspectives on historical events. In world history and Big History, we guide students to answer questions at the biggest scales—the history of our world and our Universe—using evidence from smaller scales. We also ask students to answer questions about long scales of time—the whole history of humanity—by looking at smaller bits: a revolutionary century, decades-long wars, or even just moments in time.

By this point in their BHP or WHP journey, your students are probably familiar with looking at how individual humans are connected to their communities, states, and indeed all of humanity. All these scales—of time and space—share something in common: people. But here’s a question that might throw your student: What can they learn when they switch, not just the scale, but the species of their perspective?

A diagram of the different scales of human history. By BHP, CC BY 4.0.

A diagram of the different scales of human history. By BHP, CC BY 4.0.

Anthropologist Anna Tsing explored this line of inquiry in her 2012 article “Unruly Edges: Mushrooms as Companion Species” and in her more recent book, The Mushroom at the End of the World. Tsing claims that human exceptionalism (a focus on humans as separate from the world) has historically blinded us to the webs of interdependence that link us to other species.

For example, we tend to think of human nature as something constant and unchanging. Tsing claims instead that “human nature is an interspecies relationship.” She claims that our very sense of human-ness has shifted as our lives and our work have become entangled with new species. We might try to understand this by focusing on examples such as the grains that fueled the agricultural revolution, or the cash crops that helped fuel industrialization. Instead, Tsing chooses mushrooms for her exploration.

Species, assemble

Fungi have proven exceptionally difficult to domesticate. Yet despite its reluctance to enter the “human world” of domesticated crops, the mushroom has been changed by humans and it has changed us. Tsing goes so far as to claim that “fungi are indicator species for the human condition.” They travel with us and reflect changes in our societies. For example, we can trace the spread of the British Empire by following the Serpula lacrymans fungus that caused dry rot in British ships and railroad ties.

Tsing uses the small lens of fungi to explore some big concepts, including capitalism and the plantation system. One important point is that fungi love monocultures, and thus became a danger to such modern monocultures as the sugarcane grown on the plantations of the Americas. But humans have also found innovative ways of using mushrooms, some of which have changed the course of history. Those same sugarcane planters in the Americas discovered that molasses and fungal fermentation produced rum. The result helped fuel the deadly triangle trade that forced millions more enslaved Africans into plantations in the Americas.

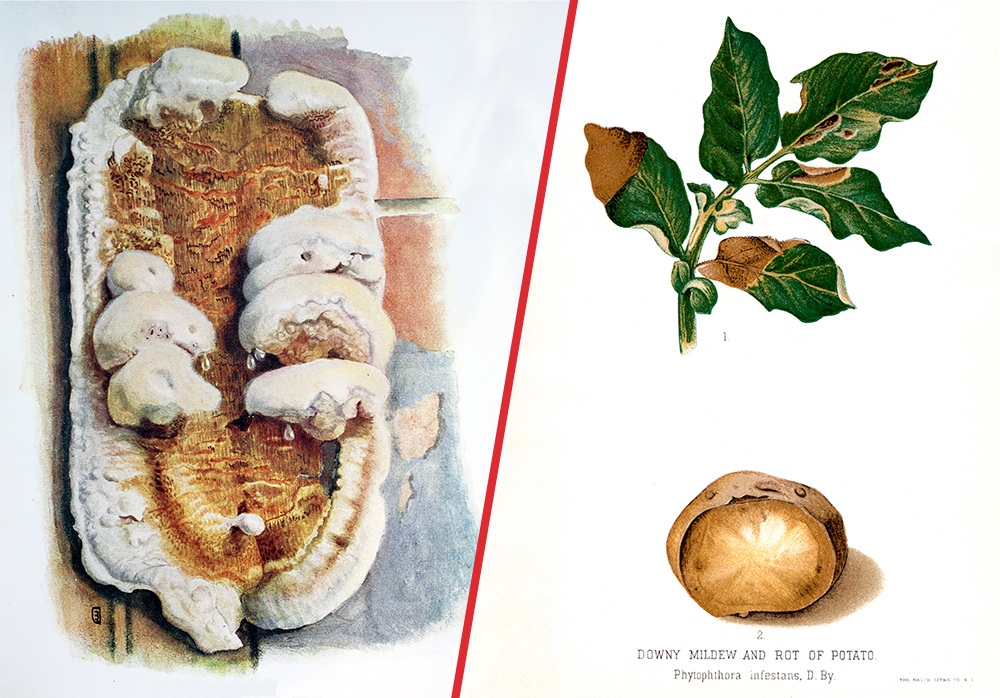

Serpula lacrymans and Phytophthora infestans. Both © Universal / Getty Images

Serpula lacrymans and Phytophthora infestans. Both © Universal / Getty Images

Relationships between fungi, humans, and other species (such as potatoes, cereals, trees, and sugarcane) produce what Tsing calls “assemblages.” These assemblages of species “cultivate each other unintentionally.”

Switching scales and species can radically transform students’ perspectives on human power. Here’s an example. Our anthropocentric perspective might prompt us to say that “humans moved species of fungi around the world.” We certainly did this with the crops we wanted to grow. Case in point: Humans intentionally carried potatoes from the Americas to Europe and farmed them as a monoculture. But fungi often used us as carriers. Say we adopt the perspective of a fungus like Phytophthora infestans, the species responsible for the blight that led to the Great Famine in Ireland. From the perspective of this fungus, we might instead say that “fungi took advantage of human expansion to propagate themselves around the world.”

Tipping the scales

Scale shifting can help students situate their own lives in relationship to history and in relationship to the other species that inhabit this planet alongside us today. In BHP and WHP, we offer resources at the individual level that help students see themselves in the big narratives and structures of history. These individual stories often challenge the large-scale historical narratives students encounter in WHP and BHP. By asking students to think about their own stories as significant evidence in understanding world history, we can make global stories more meaningful and relevant to them. What might they gain by situating their lives in relation to another companion species or an assemblage of several different species? What historical narratives might these perspectives challenge?

Parasol mushroom growing in a forest in Saxony, Germany. © Westend61 / Getty Images.

Parasol mushroom growing in a forest in Saxony, Germany. © Westend61 / Getty Images.

Here’s an exercise you can use in your own classroom to help students shift to a nonhuman perspective. Ask them to choose a nonhuman species that’s found in your area. Have them research it, and then respond to these questions:

- Is this species native to our area? If not, where did it originate and how did it come to be here?

- Do humans interact with this species? How? How has this interaction changed in the last 250,000 years?

- For BHP: How has this species changed with Thresholds 6, 7, 8, and 9?

- For WHP: How does this species affect the three course frames?

- How has human activity changed this species in the past 200 years?

- How would your life change if this species suddenly disappeared? How would its disappearance affect human communities at bigger scales?

As they answer these questions, students must constantly shift scales. From big, ecological changes wrought by industrialization to the smaller scale of community or individual impacts of the changing landscape around them, the entanglements linking our species to the species we share our environment with affect all levels of our world.

About the author: Bennett Sherry holds a PhD in history from the University of Pittsburgh and has undergraduate teaching experience in world history, human rights, and the Middle East. Bennett writes about refugees and international organizations in the twentieth century and is one of the historians working on the OER Project courses.

Cover image: Composite image: Close-up of mushroom, © Minh Hoang Cong / 500px / Getty Images and Mold spots on a white background, © iStock / Getty Images Plus. Color school rulers in centimeters and inches set, © macrovector / freepik.com and view of planet Earth world globe from space, by © doomu / freepik.com.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,