By Monica H. Green, Guest Expert

Editor's note: We’re dusting off this "vintage" blog as part of our new collection of Sourcing lesson plans. This post explores some of the essential documents regarding the Black Death, and it makes a great pre-read as you prepare yourself to teach this topic, or even something to share with your students as an extension to the lesson—particularly because they’ll encounter a source from the blog’s author as part of that lesson!

As the world moves into the third year of the present COVID-19 pandemic, many governments—out of fatigue or for other reasons—are now declaring the pandemic “over.” What we’re seeing in real time is the playing out of a profound question in epidemiology: Just how is a pandemic defined? What constitutes a pandemic’s beginning and ending? Do we say a pandemic has “begun” once a pathogen spreads to humans? If so, in the case of COVID-19 the pandemic probably began sometime in late 2019. Or did it begin in March 2020, when it was officially declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO)? And how will we know when it’s over? When the virus completely disappears? When hospitalizations decline? When the WHO tells us so? Or is there some other measure?

Major redefinitions of world historical events are a challenge to integrate into teaching. Narratives that we think of as tightly structured begin to fall apart. Arguments of causation or sequences of events that seemed clear can now seem anything but, prompting historians—and teachers—to think again.

“The Triumph of Death” a fifteenth-century fresco depicting the specter of death that continued to haunt Europe well after 1353. © Hulton Fine Art / Getty Images.

In a blog post for the OER Project Teacher Community in January 2022, Bennett Sherry offered a summary of my work redefining the geography of the Black Death as a pandemic that likely involved much larger landscapes than the regions of the Mediterranean and Europe usually included in maps and textbooks. As he noted, that redefinition of geography also involves expanding the timeline of the late medieval plague pandemic. Whereas his post focused on the reasons for pushing the origin story of the pandemic back into the thirteenth century, this blog post will turn to the question of why we should extend our narrative forward into the early modern period, when plague lived on as a continuing threat to populations in Eurasia and Africa. The present COVID-19 pandemic has heightened the urgency of learning how to talk comparatively about pandemics. Understanding how pandemics have ended—or persisted—in the past is now an important objective.

Why redefine the Black Death? Transformative new information from genetics

The gist of the story summarized by Bennett is that developments in genetics have allowed the specific strain of the bacterium that causes plague, Yersinia pestis, not only to be retrieved from fourteenth-century gravesites but also to be compared with every other completely sequenced genome of Y. pestis anywhere in the world. The initial work confirming Yersinia pestis as the culprit in the Black Death was published in 2011 and was based on samples from cemeteries in London. Since then, there have been additional retrievals of plague genomes, coming from sites all over Europe and western Russia. The result has been an increasingly refined “family tree” for the pathogen, its global history summarized in a single diagram. My published work to date has focused on how new stories about plague have been created for regions outside of Europe.

Excavation of a fourteenth-century plague cemetery in London. © Hulton Archive / Getty Images.

But the way we think about plague’s history within Europe has changed too. To understand the historical significance of the Second Plague Pandemic, we need to stop talking about the Black Death as if it were a single event that lasted only seven or eight years. Yes, the initial outbreaks of plague between 1346 and 1353 eventually disappeared from Europe. The apparent crises passed. But the pandemic was not over.

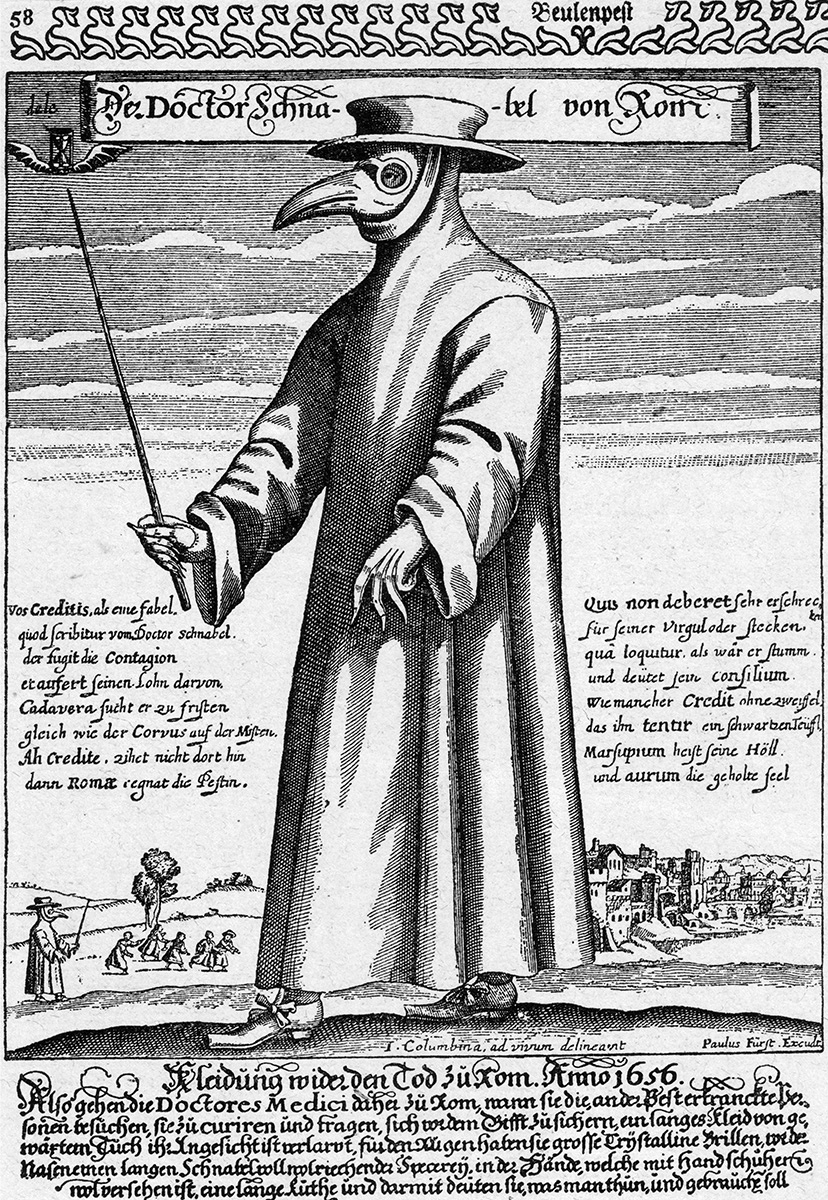

Obviously, we’ve always known that plague continued to haunt many of the same regions in Europe that were struck by the initial wave shown on maps. Separately, we’ve told stories about plague epidemics in Castille (1596–1601), in Florence (1630), in London (1665), in Marseille (1720) and dozens of other places. But we’ve been vague about how those later outbreaks were related. The result is that we too easily collapse the plague experience into narratives about the Black Death, and treat all subsequent developments (economic, political, cultural) as resulting from what happened in the late 1340s and early 1350s. Just to take one common example, students often assume the now-iconic “Plague Doctor” figure (recently transformed into an apotropaic doll for our present pandemic moment) was a medieval response to the Black Death. Far from it! That early attempt at PPE (personal protective equipment) dates from no earlier than the 1630s, nearly 300 years after the fourteenth-century outbreak.

Seventeenth-century engraving of a plague doctor wearing the iconic mask often associated with the Black Death, but which did not emerge until the 1630s. © Hulton Archive / Getty Images.

Currently, we know that whatever forces brought plague westward in the later Middle Ages did so only once. Thereafter, plague seems to have focalized—established new local reservoirs—somewhere in western Eurasia. Several new sublineages were born, perhaps even before the documented Black Death outbreaks in Europe. One of these survives to the present day in Africa as well as throughout other parts of the world. But another sublineage has been found exclusively in European and western Russian samples. With the exception of a small cluster of outbreaks in northern Europe in the 1350s and early 1360s, this latter sublineage seems to have been responsible for all subsequent outbreaks in Europe and western Russia up until plague’s disappearance in the eighteenth century. In the Ottoman world, it lasted another hundred years.

In other words, our current understanding of plague’s history in western Eurasia and Africa from the thirteenth century up to the nineteenth is that it was all one continuing pandemic, and thus the result of medieval events. This process is akin to what we have just witnessed with SARS-CoV-2: The latest variant (at this time of writing), Omicron, did not emerge out of the previous variant, Delta, circulating in 2021, but out of a strain “seeded” very early in the pandemic in 2020.

Connecting narratives: Setting Europe and the western Islamic world into a larger pandemic geography

So, what does this new narrative of plague mean for you, in your World History Project or Big History Project classrooms? Well, most of the new paradigm in thinking about the Second Plague Pandemic won’t change the way you teach about the most intense phase of plague’s intrusion into the Mediterranean and its spread into North Africa and Europe. You can still tell Black Death stories using Boccaccio or Petrarch or Ibn al-Wardi or Ibn Khatima or any of the dozens of other primary sources that teachers at all levels have relied on to convey the terror and horror of that most awful of epidemic disasters. However, beyond recognizing that new events (like the siege of Kaifeng in 1232 or that of Baghdad in 1258) might now usefully be added to our narratives about the early stages of the pandemic, we might also use this moment to recalibrate our timelines and cause-effect explanations for even more traditional elements of the pandemic stories we tell. And that is because a better understanding of why plague arrived can also inform us about why it persisted.

A nineteenth century depiction of the fourteenth-century plague as described by Boccaccio. © Bettmann / Getty Images.

First and foremost, the famous story of the siege of Caffa—for which we have relied solely on the unique testimony of the Piacenzan notary, Gabriele de’ Mussi—needs to be corrected and revised. Hannah Barker’s 2021 recalibration of the siege of Caffa story changes that narrative, showing it to be partly true, partly fiction, and entirely misleading. Importantly, Barker shows that hostilities with the Mongols of the Golden Horde played no direct role in transmitting plague. Far from being the result of bioterrorism (hurling plague-ridden bodies over the walls), plague began to spread, Barker’s revised narrative suggests, once peace was reestablished and trade embargoes lifted in 1347. She puts grain trade prominently on the agenda as an element in how/why plague was introduced into the Mediterranean, trade prompted by ongoing grain shortages in northern Italy. Forthcoming work that I have done draws on genetics to further complicate our stories of when and how plague initially entered Europe. It is likely that the grain trade continued to play a role in plague’s circulation for the next 400 years.

Such complicating stories will likely continue to appear as new work from archaeologists, bioarchaeologists, geneticists, and other scientists prompts historians to revisit narratives that previously relied only on written sources. Even simply revisiting written sources can yield radically new interpretations, such as analyses of the persecution of Jewish communities or literary responses to pandemics, which bring important nuance to the stories we have long told. Distilling this work down to simplified timelines and cause-effect narratives that students can use to build up a knowledge base about pandemics will be the work ahead.

But today’s students will be savvy consumers of such work. They have watched debates about our present pandemic’s origins, they’ve seen disagreements unfold about modes of transmission, and watched protests against public health interventions. They’ve seen empty store shelves, empty classrooms, and empty streets. We have better tools than ever before to show them that they are not alone in the hard human endeavor of coping with, and understanding, pandemics.

About the author: Monica H. Green is a historian of medicine and Global Health. A specialist on the history of medieval Europe, she has spent over forty years researching the history of the intellectual and social aspects of premodern medicine. The winner of numerous fellowships and awards for her research and teaching, she decided about fifteen years ago to press her work into more global frameworks, so that she could better understand the history of the world's major infectious diseases. Coincidentally, that was also the time that the field of genetics was making new inroads into the recovery of molecular traces of ancient pathogens. Plague and leprosy, two "medieval" diseases, were at the forefront of that research, and she has been working on both ever since then.

Cover image: This image might be the only contemporary depiction of the Black Death we have from the time of the Black Death itself. The Annales of Gilles de Muisit: The plague in Tournai, 1349, France, Brussels, Royal Library. © Photo12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments