By Trevor Getz, OER Project Team

One of the greatest challenges of teaching world history can also be an opportunity.

As teachers, we can help students identify the familiar in societies other than their own, and at the same time appreciate the differences that make every community unique. Learning world history is an exercise in recognizing the shared experiences and patterns that bind humanity together. But it is also a search to understand the great diversity of human experiences, strategies, and forms of existence. When a student can grasp both ideas and hold them in their mind together, they will have achieved a new level of understanding of the human community while also coming to grips with differences. What an enormous achievement for a world-history class!

In Unit 2 of the World History Project AP® course, students will have plenty of practice doing this. One of the big tasks facing students in this unit is identifying the similarities and differences among networks of exchange in different regions of the world from 1200 to 1450 CE. As they go through the course, they’ll have opportunities to practice one of their historical thinking skills: making connections. As they compare networks of exchange, students can explore how economic interactions among societies affected the growth of states in different regions. One illustrative example that the College Board recommends to demonstrate this relationship is the city-states of the Swahili Coast.

The Swahili city-states of East Africa in the period from 1200 to 1450 present a wonderful opportunity to illustrate the way that global trends in state-building, which were connected to expanding trade, may be uniquely shaped by local conditions, innovations, and human choices.

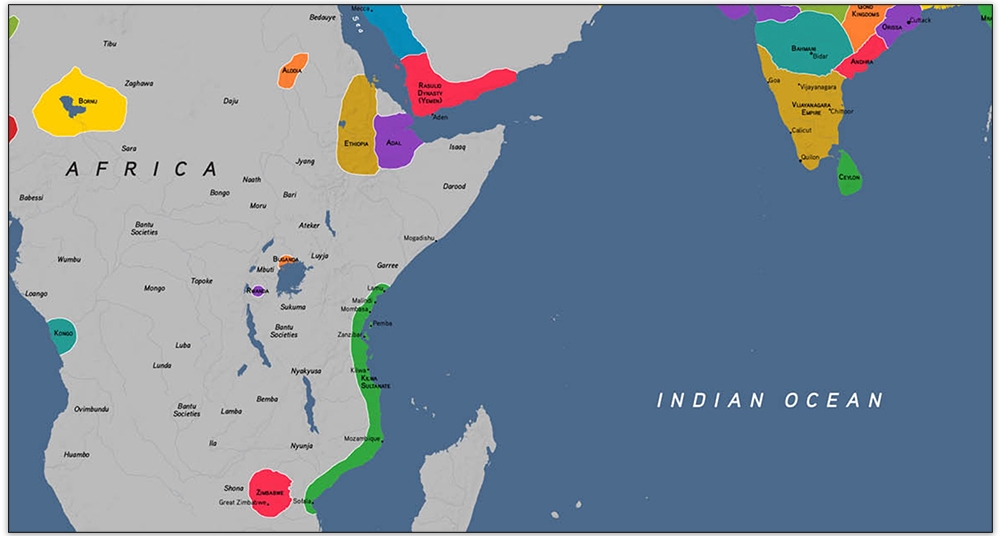

Swahili society has its origins in trading networks that emerged as long ago as 800 CE, but it was really in the fourteenth century that the Swahili language, society, and culture flourished in large coastal cities from Mogadishu (in modern-day Somalia) all the way down to Malindi and Mombasa (Kenya), and Kilwa (Tanzania). Together, these cities connected major African trading networks with the cosmopolitan Indian Ocean system.

Map of the western Indian Ocean in 1450 CE. By WHP, CC BY-NC 4.0.

Map of the western Indian Ocean in 1450 CE. By WHP, CC BY-NC 4.0.

Swahili cities mixed together both locally born and immigrant merchants. Major trading families included many Muslims from Arabia and northern India as well as entrepreneurs connected to the mining, farming, and hunting societies in the African interior. These traders imported silk and other cloth, amber, musk, and pearls from Asia, which they exchanged for valuable metals mined in southern and central Africa. Pottery and glass beads were produced in the workshops of the Swahili coast cities and exported widely across the Indian Ocean. Merchants used several different currencies in the city-states, but Kilwa, at least, minted its own copper coins.

In the fourteenth century, expanding trade changed the politics of some of these city-states, especially Mombasa and Kilwa. The most dramatic transformation was the growth of a class of wealthy merchants who began to take power from kings and sultans, which led to a greater sharing of power. Architecturally, we can see the rising power of these merchant families in their increasingly large houses made of coral, which began to dominate the major Swahili cities.

Politically, we refer to the forms of government they built as oligarchies, because groups of wealthy families controlled decision-making. Yet some scholars also call them republics because the leaders of the merchant families generally met together and made important decisions through votes. In some cities, these merchant families were multicultural, and included some Arab and Persian immigrants, some inhabitants of the Swahili coast, and some families with roots in the trading communities of the African interior. However, they were apparently all (or almost all) Muslim, and this shared religion allowed them to often work together in the collective interest of their city-state.

A 1572 image of the Swahili city of Kilwa. © Pictures from History / Getty Images

Although they shared power, these merchant families also competed against each other. Their rivalries included economic competition over trade routes. This competition often led to cultural achievements, as families of merchants tried to outdo one another by sponsoring festivals and constructing civic buildings such as mosques.

The power of these merchant oligarchies, however, wasn’t complete. Some authority was retained by Muslim clerics and the sultans. Still, the elders of the merchant clans made most of the decisions. In some city-states, such as Kilwa, they even replaced unsatisfactory rulers with their own choices several times during this period.

The ruins of the grand Mosque of Kilwa, first built in the thirteenth century and extended in the fifteenth, which demonstrates the importance of Islam to the ruling class of this East African city-state. Kilwa eventually went into decline due to changes in the trading system in the region. © Werner Forman / Getty Images.

Political systems deeply based on trade are, of course, vulnerable to economic shifts. In the Swahili case, it was the entry of the Portuguese into the region that destroyed the commercial system they had so carefully constructed. It was not Portuguese conquest that undermined the system, however. Rather, in trying to capture the gold trade from the African interior away from the Swahili city-states, the Portuguese caused wars and disruptions that upended regional trade for everyone, at least for a while. As a result, the diffuse rule by merchant families began to transform into a more centralized system after the sixteenth century, as merchant wealth and authority declined.

Yet, although transformed, the Swahili city-states didn’t disappear. In fact, they would rise to prominence again in the eighteenth century, this time mostly under the control of the Omani Empire in the Arabian Peninsula. Even today, the Swahili language and identity remains widespread and very important across East Africa.

So, is the early modern Swahili political system part of a wider pattern, or unique? It’s both. Throughout history, trade-based city-states have frequently been managed or ruled by oligarchies of merchants. Examples include ancient Carthage, the Hanseatic states of late medieval Germany, and the Fante coastal towns of nineteenth-century West Africa. The fact that this political system developed along the intensively traded Swahili coast in this period isn’t surprising.

However, the specific model of oligarchy in these cities was unique. Tied to Islam, featuring elders of trading clans, and mixing Africans with immigrants, it represented a uniquely Swahili system, one that worked well until the global disruption caused by European expansion.

About the author: Trevor Getz is a professor of African history at San Francisco State University. He has written 11 books on African and world history, including Abina and the Important Men. He is also the author of A Primer for Teaching African History, which explores questions about how we should teach the history of Africa in high school and university classes.

Cover image: Composite image, Swahili women dress in high fashion wearing elaborate kanga, late 19th century. © Pictures from History / Universal Images Group / Getty Images. African pattern, seamless vector pattern for traditional kanga clothes. © SpuVector / Shutterstock.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

-

Ane Lintvedt

-

Cancel

-

Up

0

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Comment-

Ane Lintvedt

-

Cancel

-

Up

0

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Children