Bridgette Byrd O’Connor, WHP Team

Louisiana, USA

Everyone—and I mean everyone—is telling you to wash your hands. And yes, handwashing and social distancing will help keep you healthy and prevent the spread of this coronavirus. But have you ever thought about why we wash our hands in the first place? The normal story we learn is that humans in the past were dirty, and we became cleaner over time as society became more modern. We slowly developed hygiene—the set of behaviors that we use to maintain good health. But some people question that narrative. If societies of the past—and in some cases the Neolithic past—practiced hygiene quite effectively, then it’s possible that hygiene and cleanliness are partly instinctual (hard-wired into our brains).

Behavioral scientist Valerie Curtis thinks this might be the case. She points out that many animals have grooming rituals. Chimpanzees spend hours grooming each other; cats lick themselves and each other clean; elephants use mud as an exfoliator and to keep bugs off them. So, do humans instinctively know that we should groom ourselves and stay away from sick people?

Curtis points out that people seem to avoid things that they find disgusting—vomit, human waste, open wounds and sores. Most humans find these types of bodily fluids to be off-putting, and that may be a natural reaction our body uses to keep us clean. But despite these natural reactions, the fact is that humans haven’t always been a particularly clean species by modern standards, and we do have a long history of developing new hygiene and cleanliness techniques.

There’s a saying that cleanliness is next to godliness, and in the ancient world, hygiene was often associated with the gods. The ancient Greeks made offerings to the goddess Hygieia, goddess of healing and cleanliness (we get the English word hygiene from this goddess).

The first recorded recipe for soap comes from ancient Babylon c. 2800 BCE. Today, the recipe for soap is pretty much the same as it was 5,000 years ago—animal fat mixed with lye (a chemical derived from the burning of wood). But soap in the ancient Mediterranean was used mainly for cleaning clothes, not skin. That’s not to say that people in the Mediterranean region didn’t clean themselves. Hygiene in antiquity involved rubbing oils, ashes, and clay on your body. In parts of some empires, people had access to public baths, and the wealthy had perfumes. People weren’t squeaky clean by modern standards, but they weren’t rolling around in filth either.

Left: The Greek goddess Hygieia, second century CE. By Yair Haklai, CC BY-SA 4.0. Right: A Roman strigil, which people used to scrape the oil and ashes off their skin to remove dirt, first century CE. By Walters Art Museum, public domain.

Left: The Greek goddess Hygieia, second century CE. By Yair Haklai, CC BY-SA 4.0. Right: A Roman strigil, which people used to scrape the oil and ashes off their skin to remove dirt, first century CE. By Walters Art Museum, public domain.

Communal bathing appears to date back to the Neolithic, with the Great Bath of Mohenjo-Daro in the Indus Valley being one of the first. However, this tradition of bathing seems to have developed in other areas independently of the Indus Valley, from Rome to the Americas. The Roman Empire had elaborate public bath systems. The Roman tradition of public bathing continued after the fall of the empire, but many in Christian Europe avoided baths after the church declared them sinful. Yet, the practice endured in other parts of the world. Hygiene is a central aspect of Islam, and the washing of hands and feet before entering the mosque was required. Public baths in non-Christian areas existed in abundance, from the Russe (Russians) to the Japanese. But few societies could compare to the hygiene systems of the Islamic world, except, perhaps, the Aztec Empire.

The Great Bath at Mohenjo-Daro, Indus River Valley, third millennium BCE. By Saqib Qayyum, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Baths of Alhama de Granada, Andalusia, twelfth century CE. By SuperCar-RoadTrip.fr, CC BY 2.0.

Baths of Alhama de Granada, Andalusia, twelfth century CE. By SuperCar-RoadTrip.fr, CC BY 2.0.

At its height, sanitation workers cleaned the bustling avenues of the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan (present-day Mexico City). These workers also maintained the empire’s sophisticated aqueduct and sewage systems. Spanish conquistadors commented on the cleanliness of the city and the Aztec peoples—a sharp contrast with sixteenth-century Spain. The Aztecs bathed regularly—sometimes twice a day—and used natural deodorants and breath fresheners. These hygiene rituals were unheard of in sixteenth-century Europe. The European invaders had some impressive weapons technology, but the Aztecs were repulsed by their poor hygiene.

Hand washing didn’t become common practice in Western Europe until the mid-nineteenth century. Even then, it took a while to convince people that sanitizing your hands prevented disease and infection. Nineteenth-century doctors in Vienna were offended when Iganz Semmelweis—a Hungarian doctor working in a Vienna hospital—suggested that so many women died in childbirth because of the doctors’ unsanitary practices. By contrast, the midwives’ ward had lower rates of infection than the doctors’ ward. Semmelweis realized that the doctors were performing autopsies right before they delivered babies. And they didn’t wash their hands in between! He recommended that the doctors wash their hands with a sanitizing solution to remove bacteria. The doctors ignored his advice, offended at the criticism.

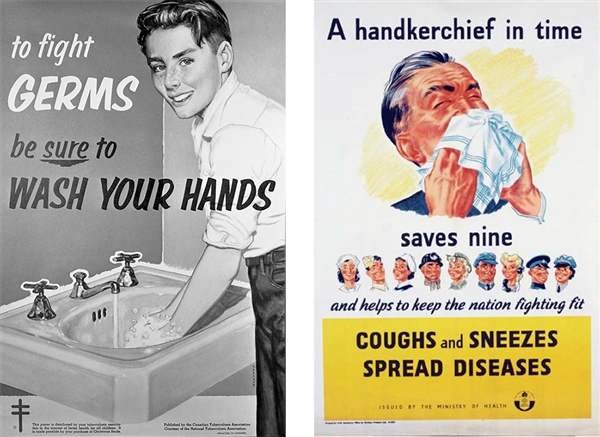

While Semmelweis’s colleagues may have dismissed his advice, the scientific evidence increasingly supported his proposal. By the early twentieth century, public health officials, armed with the discovery that viruses such as tuberculosis could be transmitted through coughing and sneezing, launched campaigns to get everyone to wash their hands and cover their mouths when they coughed or sneezed. Advertising campaigns were launched to help stop the spread of disease.

Left: Canadian Department of Health poster, 1959, by Provincial Archives of Alberta, public domain. Poster by the UK Ministry of Health, 1939–1945. By Central Council for Health Education, public domain.

Our understanding of hygiene has certainly improved, but is this understanding linked to our species’ instinctual avoidance of contamination? We know that all the hand washing you’re currently doing helps stop the spread of viruses. And thanks to centuries of medical advances, we now have vaccines and antibiotics that stop many diseases in their tracks. But what happens when you don’t have a vaccine or antiviral drugs to treat a virus? Public health officials fall back on thousands of years of human experience and tell people to wash their hands and practice social distancing, a twenty-first century term that pretty much everyone in the world now knows. Today, if a person coughs or sneezes it can cause panic. Certainly, people are afraid of catching a deadly virus, but to many, the thought of microscopic bacteria landing on them is just plain disgusting.

Sources

Becerril, J.E. and B. Jiménez. “Potable Water and Sanitation in Tenochtitlan: Aztec Culture.” Water Science & Technology: Water Supply 7, no. 1 (2007): 147-154.

Burkert, Walter. The Orientalizing Revolution: The Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992.

Curtis, Valerie A. “A Natural History of Hygiene.” Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology 18, no. 1 (2007): 11-14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2542893/.

Davis, Rebecca. “The Doctor Who Championed Hand-Washing and Briefly Saved Lives.” NPR, January 12, 2015. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/01/12/375663920/the-doctor-who-championed-hand-washing-and-saved-women-s-lives.

About the author: Bridgette Byrd O’Connor holds a DPhil in history from the University of Oxford and has taught Big History, World History, and AP US Government and Politics for the past 10 years at the high-school level. She currently writes articles and activities for the World History Project and the Big History Project. In addition, she has been a freelance writer and editor for the Crash Course World History and US History curricula.

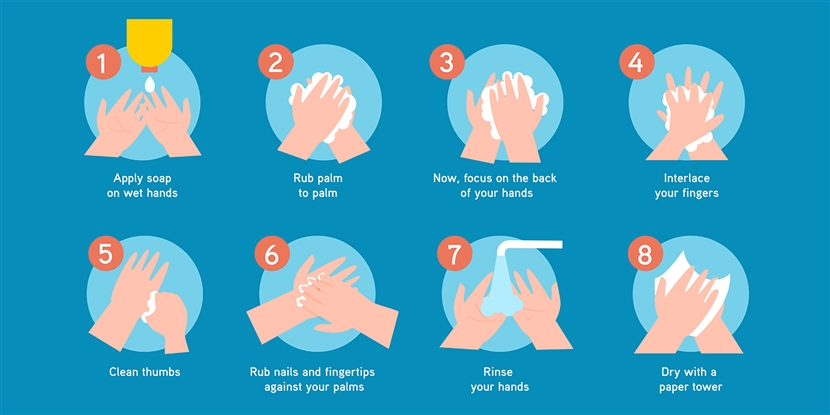

Cover image: How to wash your hands, designed by Freepik.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

-

Manisha Nanda

-

Cancel

-

Up

0

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

-

Maheen Sahoo

in reply to Manisha Nanda

-

Cancel

-

Up

0

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

-

Eric Schulz

in reply to Maheen Sahoo

-

Cancel

-

Up

0

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

-

Maheen Sahoo

in reply to Eric Schulz

-

Cancel

-

Up

0

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Comment-

Maheen Sahoo

in reply to Eric Schulz

-

Cancel

-

Up

0

Down

-

-

Reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Children