By Bennett Sherry and Bridgette Byrd O’Connor, OER Project Team

Maine, USA / Louisiana, USA

As you’re settling into the flow of a new school year, laying the foundation of literacy is probably at the front of your mind. OER Project courses contain a variety of tools to help students build literacy. Our vocabulary activities are an adaptable—and fun!—way to make sure students grasp important concepts. And Project Score offers a new curriculum to help your students become better writers. But in this blog, we’re going to focus on one of the most fundamental tools across OER Project courses.

In both BHP and WHP, we’ve designed articles and videos under the assumption that students will “read” each asset multiple times. If you’ve taught BHP or WHP before, you’re familiar with the Three Close Reads approach. In case you need a refresher, check out Eman Elshaikh’s blog post from last year. As its name suggests, the Three Close Reads (3CR) method encourages students to read the text three times. The first read is just a skim; the second is informational; and the third is conceptual, encouraging students to consider how the text connects to other texts and to the big narratives of the course. OK, OK. We can hear your students groaning from here, but really, it’s more like 1¾ reads than three full reads. And as they do it more, each read will go faster, and they’ll get more from it. Eman’s blog post highlights how you can spice up 3CR and how it can help students build lifelong habits.

But literacy isn’t just reading words on a page, and articles aren’t the only “texts” your students will encounter in OER Project courses. So, we’ve built three-ish[1] different Three Close Reads tools—one for articles, one for videos, one for graphic biographies, and one for data.

OER Project courses include a variety of videos in addition to articles. But, as you might have noticed, students sometimes tune out when the screen turns on. By approaching videos as another form of text, the 3CR method can help turn passive viewing into active learning. For example, we suggest that when you assign videos as part of a lesson, you start with a guiding question to focus students’ attention and have them read the captions or video transcripts as they watch. In addition to transcripts and captions, you’ll also see pause points in our videos. These pause points align with important concepts in the second (“understanding content”) read. The videos can be set to automatically pause at these key points so students can take a moment to contemplate and discuss or write a response to the embedded questions.

Asking students to do three close reads for a complex article or 10-minute video sounds relatively reasonable. But what about for a short, one-page comic? Don’t let the pictures fool you—WHP’s graphic biographies might look fun and easy, but there’s a lot of information to unpack! Have you ever listened to Trevor Getz talk about teaching comics? If not, stop reading right now and go watch this video (which is a part of the Teaching World History section on graphic biographies, which we’d also recommend you check out). Trevor explains how text, illustrations, and format blend together in these comics, making layers of meaning. These secondary sources are collaborations between a historian and an illustrator. So students need to also consider the intent of two different authors. All this decoding requires a new set of reading skills than those students use for articles and videos. But it’s worth the effort. By using the 3CR for Graphic Biographies, your students will grow proficient at using these illustrated stories of individuals to support, extend, and challenge the narratives they encounter elsewhere in the course—and many of these individuals do challenge our large-frame narratives (we don’t hold that against them). As with the 3CR tool for articles and videos, students begin their first read with a skim to identify who the biography is about. In the second content read, student focus on understanding the narrative of the comic, but they also start to unpack the visual elements. Finally, in the third read, students place the stories of these individuals within the larger narratives of world history.

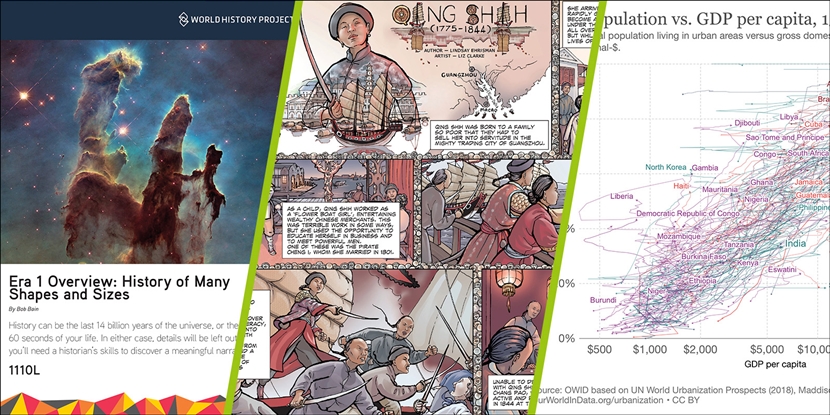

Graphic biographies (left) and Project X data explorations (right) are filled with layers of information, and they each require students to develop a new set of skills to decode historical narrative and author intent.

When students use our Three Close Reads for Data tool (last one, promise!), they’re not actually going to be reading many words. This tool focuses on the charts and graphs that students encounter in the data explorations that are part of the WHP curriculum, as well as the standalone Project X course. Yet charts still need to be read in much the same way as other types of texts. In the first read, students quickly scan the charts to identify labels and variables. At the end of this first read, students should have a general understanding of what the chart is measuring. In the second read, students are focused on content—examining the arguments contained in the chart and how it presents the data. A set of questions accompanies each 3CR lesson plan. These questions guide your students (and maybe you) through difficult charts and point you toward any larger issues hiding in the data. In the third and final read, students focus on the broad issues that each chart helps us understand: Why is it significant? What predictions can it help you make about the future? 3CR for Data will help students get more comfortable reading charts, and it will help them understand the charts you show them, but more important, they will become more proficient at evaluating the ways in which data is presented to them. After they’ve completed a few rounds of 3CR for Data, students will stop taking every chart at its word and be much more critical of the people making them!

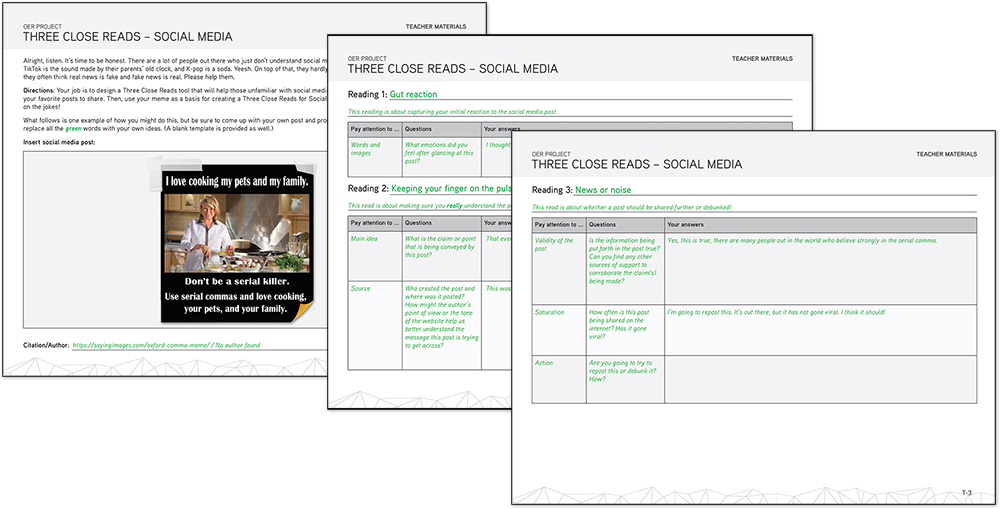

We know what you’re thinking—your students grumbled when you first introduced Three Close Reads, and now we want you to tell them that there are four different Three Close Reads?! That’s like…12 close reads! But again, we promise that veteran BHP and WHP teachers have found that their students come to accept—if not love—that this method makes them better readers and makes learning easier. But still, maybe your students deserve a little payback. If you’re like us, Zoomer humor is perplexing, and TikTok is the sound a clock makes. To help them understand how helpful 3CR can be, ask your students to develop a 3CR for Social Media using this activity—for you. What tool can they create that will help you finally understand Kylie Jenner and K-pop stans? (Please note that this activity is not in BHP or WHP. However, if you like it or have feedback on it, please let us know in the comments!)

Do you have tips for how to convince students to buy in to Three Close Reads? Get inspired and inspire others by sharing your thoughts in the OER Project Online Teacher Community.

If you’re looking for more literacy support, check out Erik Christensen’s blog post this month as well as the live literacy discussion from the OER Conference for Social Studies, featuring Erik, Andrew Del Calvo, and Abby Reisman. Looking for even more? Explore these nine Track Talks, covering different elements of literacy, from this year’s OC for SS.

[1] Why “three-ish”? While we don’t have a standalone tool for 3CR with videos, we offer the same kind of support via the features described in the next paragraph.

About the authors

Bennett Sherry holds a PhD in history from the University of Pittsburgh and has undergraduate teaching experience in world history, human rights, and the Middle East. Bennett writes about refugees and international organizations in the twentieth century. He is one of the historians working on the OER Project courses.

Bridgette Byrd O’Connor holds a DPhil in history from the University of Oxford and has taught the Big History Project and World History Project courses and AP US government and politics for the past 10 years at the high school level. She currently writes articles and activities for WHP and BHP. In addition, she has been a freelance writer and editor for the Crash Course World History and US History curricula.

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

For full access to all OER Project resources AND our amazing teacher community,

Top Comments